The Unsung Legends: White Massacres and the Shadow History of New Mexico

America, a land forged in grand narratives and epic tales, is rich with legends. From the towering lumberjack Paul Bunyan to the pioneering spirit of Davy Crockett, these stories often celebrate courage, ingenuity, and the relentless march of progress across a vast continent. Yet, beneath the polished surface of these triumphant myths lies another layer of legends – darker, more complex, and often suppressed. These are the legends born of conflict, dispossession, and violence, whispered in communities, enshrined in oral histories, and etched into the very landscape. Among the most potent and least acknowledged of these are the "White Massacres" – not a single event, but a pervasive pattern of violence perpetrated by white settlers and the U.S. military against indigenous peoples, particularly in the crucible of cultures that is New Mexico. To understand these unsung legends is to confront a more complete, and often harrowing, truth about America’s past.

The term "White Massacre" itself is striking, immediately flipping the script on more commonly known historical events where the term "massacre" is applied to indigenous resistance. It forces us to consider the perspective of the victimized, to acknowledge the systemic violence that underpinned much of westward expansion. In New Mexico, this phenomenon is not a singular, easily identifiable incident like Wounded Knee or Sand Creek, but rather a tragic tapestry woven from countless skirmishes, punitive expeditions, forced removals, and deliberate acts of annihilation that occurred over centuries. It represents a collective trauma, a foundational legend for the indigenous communities who endured it, shaping their identity, resilience, and ongoing struggle for justice and recognition.

New Mexico, with its deep historical roots, offers a particularly stark illustration of these hidden legends. Long before the arrival of Europeans, the region was home to thriving, sophisticated indigenous cultures – the Pueblo peoples, with their ancient villages and intricate social structures, and the nomadic Apache and Navajo nations, renowned for their adaptability and warrior traditions. The arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century initiated a brutal period of colonization, marked by forced conversions, enslavement, and violent suppression of native beliefs and practices. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, a stunning act of indigenous unity and resistance, temporarily expelled the Spanish, a legendary uprising in its own right, but the colonial patterns of domination were re-established.

However, it was the mid-19th century, with the American acquisition of New Mexico following the Mexican-American War, that ushered in a new, intensified era of conflict and the widespread pattern of what we might term "white massacres." Fueled by Manifest Destiny, the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward, American settlers and the U.S. Army embarked on campaigns designed to "pacify" and dispossess indigenous populations to clear the way for settlement and resource extraction. The narrative of the brave pioneer taming the wilderness often obscured the reality of brutal military campaigns and the systematic destruction of native ways of life.

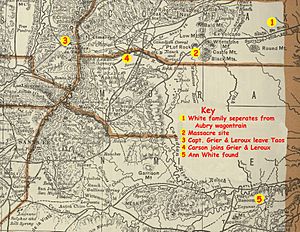

One of the most infamous, yet often sanitized, examples of this period is the Long Walk of the Navajo (Diné). Beginning in 1864, under the command of Colonel Kit Carson (a figure often celebrated as a frontier hero), thousands of Navajo and some Mescalero Apache were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in what is now northeastern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico. Driven on foot over hundreds of miles, many died from starvation, exposure, and disease. Their destination was Bosque Redondo, a desolate, barren reservation near Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico.

Bosque Redondo was not merely a relocation camp; it was, in essence, a concentration camp, a failed social experiment designed to assimilate the Navajo into American agricultural life. Conditions were horrific. Crops failed, water was scarce and contaminated, and the captives were subjected to raids by other tribes, as well as the abuses of the U.S. Army. Estimates vary, but thousands perished during the Long Walk and their four years of internment. For the Navajo, the Long Walk is not just a historical event; it is a foundational legend of suffering, resilience, and survival, a story passed down through generations, shaping their collective memory and identity.

As one Navajo elder, Annie Dodge Wauneka, daughter of Chief Henry Chee Dodge, recounted: "When the Navajo came back from Fort Sumner, they had nothing. They started over from scratch. It was a terrible, terrible time for our people. They say if you hear the wind blowing at Fort Sumner, it is the cries of the Navajo." This poignant testimony underscores how such events transcend mere historical fact to become living legends, imbued with deep emotional and spiritual significance.

Beyond the scale of the Long Walk, countless smaller, localized "white massacres" unfolded across New Mexico. Punitive expeditions against Apache bands, often in retaliation for raids (which themselves were often responses to encroachment and resource depletion), frequently resulted in the indiscriminate killing of women, children, and the elderly. Villages were burned, food supplies destroyed, and traditional hunting grounds rendered unusable. These were not always documented with precision by the victors, but they live on in the oral histories of the Apache and Pueblo peoples, a testament to enduring trauma and resistance.

The American perception of Native Americans as "savages" or "hostiles" served to dehumanize them, making such atrocities easier to justify and subsequently erase from mainstream historical narratives. The prevailing mythology of the frontier – one of empty lands waiting to be civilized by brave pioneers – actively suppressed any acknowledgment of the prior inhabitants or the violence required to dispossess them. This selective memory created a void where these "white massacres" should have been, leaving them to fester as unacknowledged legends within the affected communities.

The legacy of these events is not confined to the past. Intergenerational trauma continues to impact Native American communities in New Mexico, manifesting in social, economic, and health disparities. The loss of land, language, and cultural practices, directly stemming from these historical acts of violence and displacement, represents wounds that are still healing. Yet, these communities also embody immense resilience. The legends of survival, of cunning evasion, of spiritual strength in the face of overwhelming odds, are equally powerful.

Today, there is a growing movement to confront these darker legends of America. Historians, archaeologists, and indigenous scholars are working to uncover and amplify these suppressed histories. Museums are beginning to tell more inclusive stories. Efforts to repatriate ancestral lands and sacred items, and to restore indigenous languages and cultural practices, are acts of remembering and healing. The very act of naming these events "white massacres" is a crucial step in reframing the narrative, in acknowledging the perpetrators and the victims, and in challenging the comfortable myths that have long dominated American self-perception.

For instance, the Apache and Navajo nations have established cultural centers and educational programs dedicated to preserving the memory of the Long Walk and other historical injustices. They are ensuring that the cries in the wind at Fort Sumner are not forgotten, but understood as a vital part of their ongoing journey. These efforts transform the "massacres" from mere historical footnotes into living legends – cautionary tales, sources of strength, and powerful calls for justice.

In conclusion, the legends of America are far more intricate than the heroic tales often presented. They encompass not only the celebrated triumphs but also the profound tragedies, the hidden narratives of violence and dispossession that shaped the nation. The "white massacres" of New Mexico, interpreted not as a single event but as a pervasive historical pattern, represent a critical component of these unsung legends. By acknowledging and integrating these difficult truths into our collective understanding, we move closer to a more honest, comprehensive, and ultimately, more just American story. It is through confronting these shadow legends that we can truly begin to heal the wounds of the past and forge a future built on truth, respect, and reconciliation.