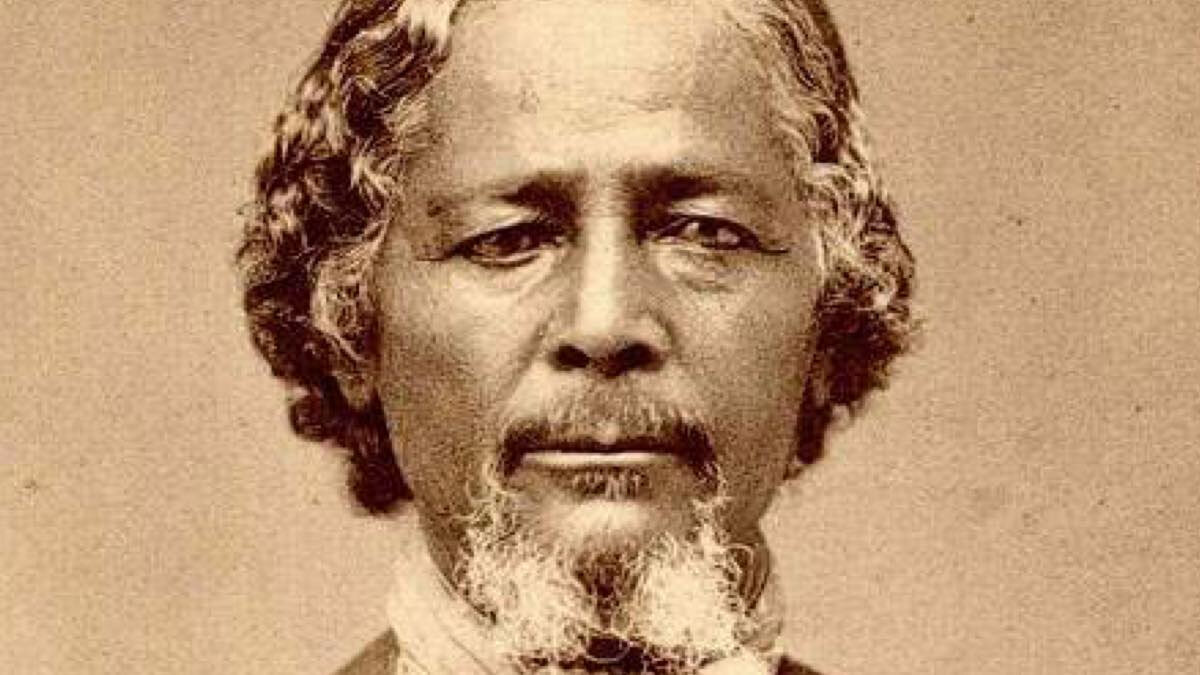

The Unsung Moses: Benjamin "Pap" Singleton and the Great Exodus to Kansas

In the annals of American history, few figures embody the sheer will for self-determination and the quest for true freedom as profoundly as Benjamin "Pap" Singleton. Born into slavery in 1809, Singleton transcended the brutal confines of his birth to become an improbable leader, an entrepreneur of liberation, and a guiding light for thousands of African Americans seeking refuge from the tyranny of the post-Reconstruction South. His vision, tenacious organizing, and unwavering belief in land ownership as the bedrock of true emancipation sparked one of the most significant internal migrations in American history: the Great Exodus to Kansas.

The period immediately following the Civil War and the promise of emancipation was, for many African Americans, a cruel mirage. While the chains of chattel slavery were broken, new, insidious forms of oppression quickly took root. The "Black Codes" and later "Jim Crow" laws systematically stripped freedmen of their newly won rights. Economically, the sharecropping system trapped families in perpetual debt, a cycle of poverty indistinguishable from serfdom. Politically, intimidation, violence, and outright fraud, often perpetrated by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, disenfranchised Black voters. The promise of "forty acres and a mule" had evaporated, replaced by a landscape of fear, injustice, and economic exploitation.

It was in this crucible of despair that Benjamin Singleton, a man who had escaped slavery multiple times before finally securing his freedom in Canada and later settling in Detroit, began to forge his extraordinary path. Singleton, known affectionately as "Pap" for his age and patriarchal wisdom, was not an educated man in the formal sense, but he possessed an acute understanding of the systemic forces at play and an unshakeable conviction that true freedom could only be cemented by economic independence and community self-reliance. He had seen the broken promises, the violence, and the economic bondage firsthand, and he knew that for Black Americans to truly thrive, they needed their own land, their own communities, and their own destiny.

Singleton’s initial efforts to secure land for his people began in Tennessee in the early 1870s. He formed the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association, aiming to purchase tracts of land for Black families to farm independently. He believed that if African Americans could own their own farms, grow their own food, and build their own homes, they could escape the predatory sharecropping system and the whims of white landowners. "My people have been freed," Singleton is reported to have said, "but they are still in bondage. They need land."

However, the dream of a Black-owned community in Tennessee proved largely stillborn. White landowners were often unwilling to sell land to Black associations, or they demanded exorbitant prices. The economic conditions for freedmen were too dire to amass significant capital. Singleton quickly realized that the South, steeped in its history of racial animosity and determined to maintain its cheap labor force, was not fertile ground for his vision. He needed to look west.

His gaze settled on Kansas. The "Sunflower State" held a special allure for African Americans. It was the land of John Brown, a battleground in the fight against slavery, and a symbol of freedom. Crucially, vast tracts of land were available under the Homestead Act, offering 160 acres to anyone who would settle and improve it for five years. To Singleton, Kansas represented a new "Promised Land," a place where Black Americans could build a future free from the specter of racial oppression and economic servitude.

Beginning in the mid-1870s, Singleton transformed from a local organizer into a tireless evangelist for western migration. He crisscrossed Tennessee, distributing handbills, circulars, and pamphlets that painted a vivid picture of opportunity in Kansas. His agents, often trusted community members, spread the word through churches, lodges, and informal gatherings. "Go to Kansas!" was the clarion call, promising not just land, but also schools, churches, and the dignity of self-governance. He spoke of Kansas as a place where "the Negro would be free indeed."

The message resonated deeply with a population desperate for change. The cotton economy had collapsed in many parts of the South, leaving many Black families destitute. Violence against African Americans was rampant and often unpunished. The political gains of Reconstruction were rapidly eroding. Singleton’s message offered not just hope, but a concrete plan for escape and a blueprint for a better life.

The trickle of migrants soon became a flood, earning the movement the name "The Great Exodus" and its participants "Exodusters." Between 1879 and 1880 alone, an estimated 6,000 to 20,000 Black Americans, primarily from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Tennessee, made the arduous journey to Kansas. They traveled by steamboat up the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, by train, and often, on foot, carrying what few possessions they had. They were driven by a powerful yearning for a place where, as one Exoduster famously declared, "we can live and be free, and not be molested by every man that comes along."

Upon arrival in Kansas, the Exodusters faced immense challenges. Many arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs, unprepared for the harsh prairie climate, and lacking the tools or capital to immediately establish farms. Aid societies, both Black and white, emerged to help, providing food, shelter, and medical care. Despite these daunting beginnings, the Exodusters, guided by Singleton’s principles of self-reliance, began to carve out new lives. They established communities like Nicodemus, Dunlap, and Singleton Colony, transforming the barren prairie into vibrant, self-sufficient towns.

Nicodemus, founded in 1877 and named after a legendary slave who first achieved freedom, became the most famous of these settlements. Its founders, most of whom were from Kentucky, shared Singleton’s vision of an all-Black community. Despite droughts, blizzards, and initial skepticism from white Kansans, Nicodemus persevered. By the 1880s, it boasted several stores, a post office, a school, churches, and a newspaper. It was a testament to the resilience and determination of the Exodusters and the power of their collective vision.

The scale of the Exodus did not go unnoticed, particularly in the South. White Southerners, fearing a mass exodus of their cheap labor force, reacted with alarm and hostility. Newspapers denounced the migration as a "negro fever" or a conspiracy. Southern politicians and landowners tried to block river access, detain migrants, and spread misinformation, claiming the Exodusters were being lured away by false promises. This backlash further solidified Singleton’s conviction that leaving the South was the only viable option for his people.

The controversy surrounding the Exodus became so significant that the U.S. Senate launched an investigation in 1879, known as the "Report and Testimony of the Select Committee of the Senate to Investigate the Causes of the Removal of the Negroes from the Southern States to the Northern States." Benjamin "Pap" Singleton was called to testify. His appearance before the committee was a defining moment, allowing him to articulate his vision and the plight of his people on a national stage.

With dignity and conviction, Singleton explained the motivations behind the Exodus. He refuted claims that the migration was politically orchestrated or that Exodusters were being misled. He laid bare the brutal realities of life in the post-Reconstruction South: the economic exploitation, the denial of political rights, and the constant threat of violence. "We are simply seeking to better our condition," Singleton told the senators, "there is no hope for us in the South. We want to go where we can get land and have our rights."

When asked by a senator if anyone had urged him to undertake the migration, Singleton famously declared, "I am the whole cause of the Kansas immigration!" He explained that his motivation stemmed from witnessing his people’s suffering: "I told them that if they would come out to Kansas and take these lands, they would be free and independent." His testimony was a powerful indictment of the South’s failure to uphold the promises of emancipation and a testament to the Black community’s agency in seeking their own liberation.

Though the grand scale of the Exodus eventually subsided, partly due to the economic depression of the early 1880s and the difficulty of establishing new lives on the prairie, Singleton’s spirit remained undimmed. He continued to advocate for Black land ownership and self-sufficiency, even attempting to organize a migration to Cyprus and later to Africa. He formed the National Colored Industrial Association, dedicated to promoting industrial education and economic independence for African Americans. Benjamin "Pap" Singleton died in 1892, leaving behind a legacy far greater than the recognition he received in his lifetime.

Benjamin "Pap" Singleton may not be a household name, but his legacy as "The Father of the Exodus" is indelible. He was a visionary who understood that true freedom required economic empowerment and self-determination. He was an organizer who, despite lacking formal education, mobilized thousands with a message of hope and opportunity. He was a beacon of resilience in a time of profound despair, guiding his people towards a promised land of their own making.

The Great Exodus to Kansas, spurred by Singleton’s unwavering belief, stands as a powerful testament to the agency of African Americans in shaping their own destiny. It was a movement born not of external manipulation, but of an internal yearning for dignity, equality, and the fundamental right to own a piece of the earth. Singleton’s story reminds us that even in the darkest of times, the spirit of freedom, when nurtured by courageous leadership and collective action, can move mountains and transform the lives of thousands. His vision for land, liberty, and self-reliance continues to resonate, a timeless reminder of the enduring struggle for justice and the profound power of a people determined to be free.