The Unsung Sentinels: Butterfield Overland Despatch Stage Stations and the Pulse of the American West

In the mid-19th century, as the United States grappled with the vastness of its newly acquired western territories, the need for reliable communication and transport became paramount. The roar of a stagecoach, the thundering hooves of fresh horses, and the weary but hopeful faces of passengers were the visible signs of this ambition. But beneath this grand spectacle, the true pulse of the Butterfield Overland Despatch beat in its network of stage stations – unsung, isolated, and often perilous outposts that served as the very lifeblood of America’s first great transcontinental mail and passenger service.

These stations, stretching across nearly 2,800 miles of unforgiving terrain, were far more than mere stopping points. They were the mechanical heart of an audacious enterprise, the brief oases in an endless desert, and the frontline homes for the hardy souls who kept the wheels of westward expansion turning. Their story is one of immense hardship, incredible resilience, and a testament to the human drive to conquer distance and connect a burgeoning nation.

The Vision and the "Oxbow Route"

The genesis of the Butterfield Overland Despatch lay in the Overland Mail Act of 1857, which authorized a six-year, $600,000 annual contract for a semi-weekly mail service between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Coast. John Butterfield, a visionary businessman and founder of American Express, won the coveted contract, promising a schedule of just 25 days for the grueling journey. His rallying cry, oft-quoted to his employees, encapsulated the demanding nature of the task: "Remember, boys, nothing on God’s earth must stop the United States Mail!"

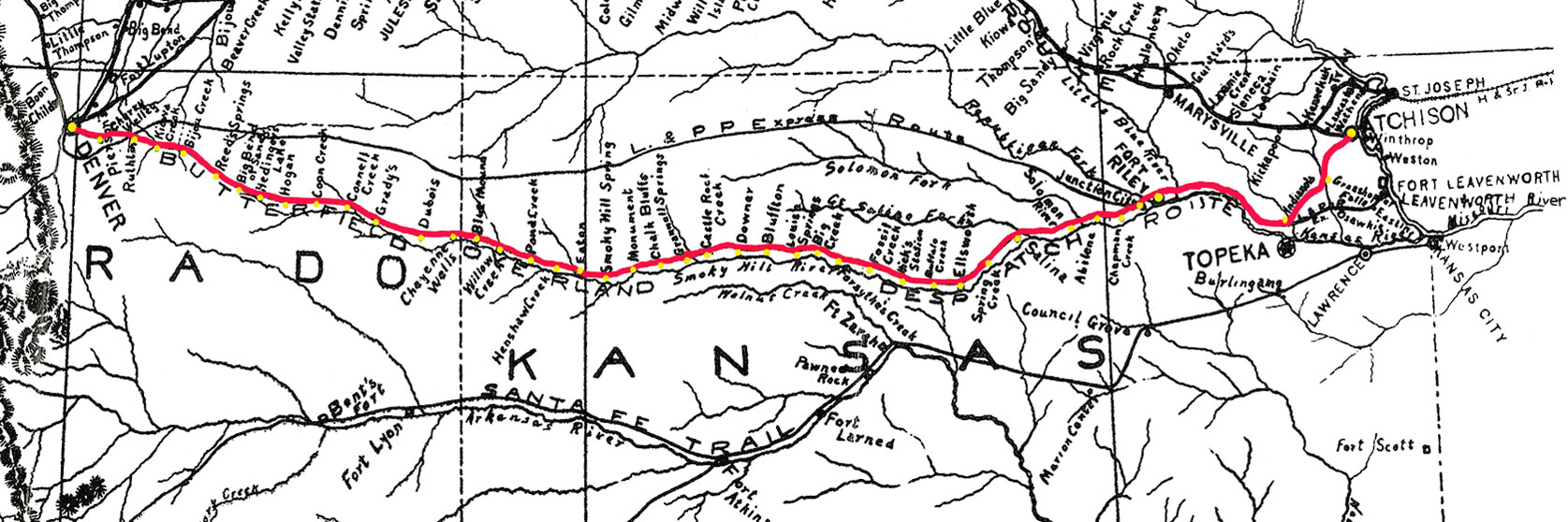

The chosen route, however, was politically contentious. Known as the "Oxbow Route" due to its sweeping southern arc through Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Southern California, it avoided the northern states, a decision driven by Southern political influence in Washington D.C. While politically expedient, it meant traversing some of the most desolate and dangerous landscapes imaginable – scorching deserts, treacherous mountains, and territories inhabited by often hostile Native American tribes.

To conquer this vast distance, Butterfield built an empire of infrastructure. Over 2,000 horses and mules, 250 stagecoaches (many of them the iconic Concord coaches), and hundreds of employees – drivers, stock tenders, blacksmiths, and station masters – were marshaled. At the core of this operation were the 140 to 150 stage stations, spaced roughly 10 to 20 miles apart, each designed for a specific purpose.

The Anatomy of a Stage Station: An Oasis in the Wilderness

Butterfield’s stations fell into two primary categories: "swing stations" and "home stations." Swing stations were smaller, often consisting of little more than a stable, a corral, and a rudimentary shelter for the stock tender. Their sole purpose was to quickly change out the teams of horses or mules, allowing the stagecoach to continue its relentless pace with minimal delay. Here, fresh, eager animals would be hitched, and the exhausted team turned out to rest, graze, and await the next inbound coach.

Home stations, on the other hand, were the true hubs of the operation. These larger outposts offered more substantial facilities: a main dwelling that often served as a combined living quarter, dining room, and office for the station master; larger corrals and stables; a blacksmith shop for repairs; and, crucially, a reliable source of water, whether from a well, spring, or river. Passengers could alight here for a brief respite, a hot (or at least warm) meal, and a chance to stretch their cramped limbs. For the stagecoach drivers, these were opportunities to swap out with a fresh driver and catch a few hours of much-needed sleep.

Life at a Butterfield station was one of profound isolation and constant vigilance. Station masters, often accompanied by their families, were responsible for maintaining the stock, housing, and supplies. Their days were dictated by the arrival and departure of the coaches, each bringing a brief flurry of activity before the silence of the desert once again enveloped them. "Our station was just a speck on the map, if it was even on the map," recalled one anonymous station hand in a later account. "But it was home, and it was the lifeline for those coaches."

Hardship, Hunger, and Hope

The challenges faced by those manning the stations were immense. Water, especially in the arid Southwest, was a constant struggle. Many stations were strategically located near scarce springs or rivers, but even these sources could dry up, forcing water to be hauled for miles in barrels. Food, too, was basic and often monotonous. Travelers often complained of meals consisting of "salt pork, hardtack, and weak coffee," though for the station staff, even this simple fare required considerable effort to procure and prepare. Fresh meat, when available, came from hunting or the occasional herd of cattle, but vegetables and fruits were rare luxuries.

The threat of danger was ever-present. Raids by Native American tribes, particularly in Arizona and Texas, were a constant concern. Many stations were fortified, with thick adobe walls and rifle slits, and station masters were expected to be armed and ready to defend their posts. Bandits, too, saw the stages as tempting targets, though the mail itself was rarely stolen, largely due to the formidable reputation of the Butterfield company and the severe penalties for mail robbery.

Disease, accidents, and the sheer monotony of isolation also took their toll. Medical care was non-existent, and a broken bone or a severe fever could be a death sentence. Yet, despite these hardships, the stations persisted, their lights burning bright against the vast, dark canvas of the American frontier.

A Passenger’s Perspective: Brief Reprieve from "Hell on Wheels"

For the passengers, the sight of an approaching stage station was a profound relief. A journey on the Butterfield Overland Despatch was, by all accounts, an ordeal. Cramped into a coach with nine fellow travelers, often for days on end without a break, subjected to incessant jolting and dust, and with no opportunities for proper hygiene, it earned nicknames like "hell on wheels."

"The ride was a torture, a constant agony of bumping and swaying," wrote Waterman L. Ormsby, a reporter for the New York Herald who chronicled the first eastbound trip in 1858. "But the stations, crude as many of them were, were like heaven. A moment to stretch, to wash the dust from one’s face, to eat a warm meal, however simple, was a blessing beyond measure."

These brief stops, typically 30 minutes at home stations and just a few minutes at swing stations, were essential for both physical and mental recuperation. They offered a fleeting glimpse into the rugged frontier life, a chance to exchange a few words with the grizzled station master or a local prospector, before being called back to the coach for another segment of the arduous journey. The stations, therefore, were not just logistical necessities; they were vital psychological anchors for those undertaking the epic voyage.

The Legacy of the Short-Lived Empire

The Butterfield Overland Despatch, with its network of stations, operated for a remarkably short period – from September 1858 to March 1861. Its demise was not due to a lack of success or profitability, but to the gathering storm of the American Civil War. As the Southern states seceded, the "Oxbow Route" became politically untenable and militarily vulnerable. In March 1861, the government ordered the route abandoned, and the entire operation, including its vast infrastructure of stations, stock, and equipment, was moved north to the Central Overland Route through Wyoming and Utah, eventually becoming part of the legendary Wells Fargo & Company.

Despite its brevity, the Butterfield Overland Despatch and its stage stations left an indelible mark on American history. It proved the viability of transcontinental travel and mail delivery, shortening the perceived distance between the East and West and fostering a sense of national unity. The stations, though many have long since vanished, leaving behind only crumbling foundations or forgotten names on old maps, were pioneers in their own right. They represented the human capacity to adapt, endure, and build against all odds.

Today, the faint echoes of the stagecoach’s horn, the rumble of its wheels, and the quiet determination of those who manned these remote outposts can still be felt along the old Butterfield trail. The stage stations were more than just buildings; they were the beating heart of a grand adventure, the unsung sentinels that helped connect a nation, one weary mile and one welcome stop at a time. They stand as a powerful reminder of the relentless spirit that shaped the American West.