The Unsung Stand: Monocacy, The Battle That Saved Washington

In the annals of American history, certain battlefields resonate with the echoes of momentous sacrifice: Gettysburg, Antietam, Vicksburg. Yet, nestled amidst the rolling farmlands and suburban sprawl of Frederick, Maryland, lies Monocacy National Battlefield, a site whose crucial role in the Civil War is often overshadowed, its profound impact on the nation’s capital frequently forgotten. Here, on a sweltering July day in 1864, a desperate gamble by Union forces bought precious time, a sacrifice that arguably saved Washington D.C. from Confederate capture and profoundly influenced the course of the war.

The summer of 1864 was a grim period for the Union. General Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign had bogged down in a brutal stalemate around Petersburg, Virginia, inflicting staggering casualties on both sides. Morale in the North was plummeting, and President Abraham Lincoln faced a challenging re-election bid. Seizing on this moment of Northern weariness, Confederate General Robert E. Lee dispatched Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s veteran Second Corps – approximately 14,000 men – on an audacious flanking maneuver. Early’s objective was clear: sweep through the Shenandoah Valley, threaten Washington D.C., and potentially force Grant to detach forces from Petersburg, thus relieving the pressure on Richmond.

Early’s raid was swift and alarming. His troops moved with remarkable speed, brushing aside scattered Union resistance, burning the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and crossing into Maryland. The specter of Confederate invasion loomed large over the unprepared capital. Washington D.C. was heavily fortified, but its garrisons were largely composed of veteran heavy artillery regiments serving as infantry, clerks, convalescents, and hastily armed civilians. The bulk of its combat-ready troops were with Grant. As Early’s forces approached Frederick, the only significant Union force positioned to block their path was a motley collection of troops under the command of Major General Lew Wallace.

Wallace, a man whose military career had been marred by controversies, including his perceived tardiness at Shiloh, was then commanding the Middle Department, based in Baltimore. He was a political appointee with a passion for literature, who would later achieve enduring fame as the author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. At Monocacy, however, his literary pursuits were far from his mind. Recognizing the immense danger, Wallace hastily assembled a patchwork command: veterans from the Sixth Corps (dispatched by Grant), newly recruited "Hundred Days Men," garrison troops, and even some convalescents. Outnumbered by more than two-to-one, Wallace understood his mission was not to win a decisive victory, but to delay Early, to buy time for Washington’s defenses to be adequately manned.

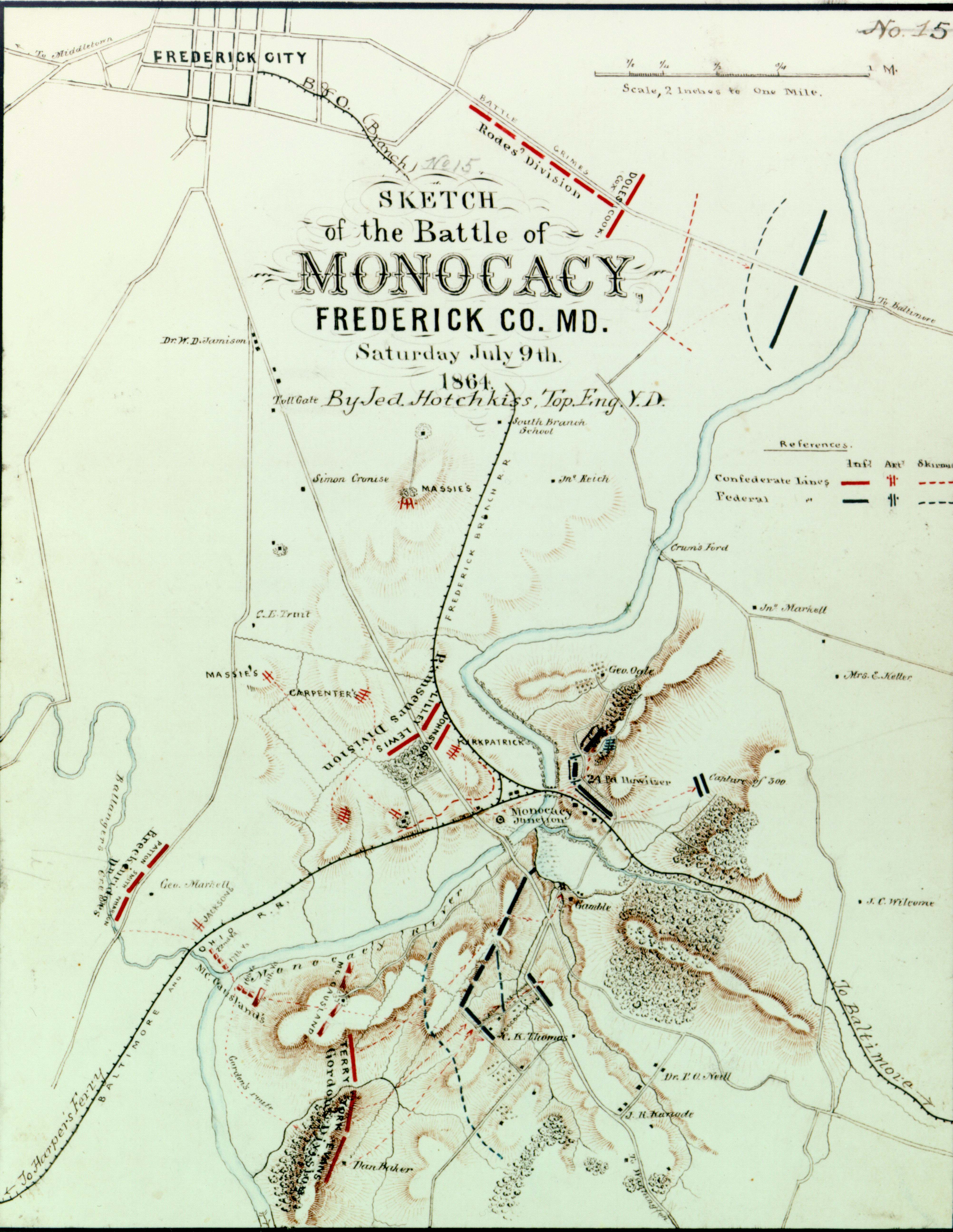

The strategic importance of Monocacy Junction was undeniable. Located just south of Frederick, it was a critical transportation hub where the Georgetown Pike (leading directly to Washington D.C.), the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and the Monocacy River converged. Controlling this junction meant controlling the arteries to the capital. Wallace strategically positioned his forces along the east bank of the Monocacy River, utilizing the natural barrier and the bridges to his advantage. His defensive line stretched for miles, from Worthington Ford in the south to the covered wooden bridge of the Georgetown Pike and the B&O Railroad bridge to the north.

On the sweltering morning of July 9, 1864, Early’s Confederates launched their assault. Initially, they engaged Wallace’s left flank, attempting to cross the river at Worthington Ford. This was met with stubborn resistance from Union troops, including elements of the 1st Maryland Veteran Volunteer Infantry, who fought fiercely to defend their home state. As the fighting intensified, Early realized the strength of Wallace’s position on the east bank. He then ordered a significant portion of his force, under Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, to execute a wide flanking maneuver to the south, crossing the Monocacy and attacking Wallace’s left wing from the vulnerable west bank.

The ensuing engagement around the Worthington and Thomas Farms was fierce and bloody. Gordon’s seasoned Confederates, veterans of many campaigns, crashed into Wallace’s relatively inexperienced and thinly stretched lines. Despite being heavily outnumbered and outflanked, Wallace’s men fought with extraordinary courage and tenacity. Union artillery positioned on the east bank poured fire into the advancing Confederate ranks. "The Confederates charged with a yell," recalled one Union soldier, "and we met them with a volley that staggered them, but they came on again like devils." The fighting devolved into a brutal close-quarters struggle, particularly around the Thomas Farm, where Union lines bent but did not break immediately.

Wallace, understanding the dire need for delay, fed his reserves into the fray, conducting a series of desperate counterattacks and shifting his troops to shore up crumbling sectors. The sheer grit and determination of the Union soldiers, many of whom had never seen combat, bought precious hours. However, by mid-afternoon, the overwhelming numerical superiority and combat experience of Early’s veterans began to tell. Wallace’s lines were stretched to their breaking point, and with the threat of being completely enveloped, he ordered a tactical retreat towards Baltimore.

The Battle of Monocacy was, in terms of battlefield outcome, a Confederate victory. Early had cleared the path to Washington, albeit at a cost. Union casualties were significant, approximately 1,294 killed, wounded, or captured, compared to Early’s loss of about 700-800 men. Yet, strategically, Monocacy was a resounding Union triumph. The precious hours Wallace’s men bought proved invaluable. During the battle, telegraph wires buzzed with frantic messages, and reinforcements, notably elements of the veteran VI Corps, were rushed by rail and forced march to Washington D.C. By the time Early’s exhausted troops arrived at the formidable defenses of Fort Stevens on the outskirts of Washington the following day, July 10, the ramparts were manned by battle-hardened Union veterans.

Early probed the defenses at Fort Stevens on July 11 and even witnessed President Lincoln himself observing the action from the parapet, reportedly under fire. But the opportunity had passed. The delaying action at Monocacy had allowed the capital to be adequately defended. Facing strong resistance and knowing his window of opportunity had closed, Early wisely chose not to launch a full-scale assault against the now-reinforced fortifications. He ordered a retreat back into Virginia, his audacious raid thwarted.

Lew Wallace, initially criticized for the tactical defeat, was later vindicated by Grant himself, who acknowledged the crucial role Monocacy played. "General Wallace," Grant wrote, "with a part of the force under his command, met the enemy at Monocacy, and though it was a severe defeat for us, it detained the enemy and enabled the Sixth Corps to get up for the defense of Washington." Monocacy became known as "The Battle That Saved Washington," a testament to the strategic foresight of Wallace and the courage of his disparate troops. Had Early taken Washington, the political and psychological ramifications for the Union, especially in an election year, would have been catastrophic. It might have even led to European intervention or a negotiated peace on Confederate terms.

Today, Monocacy National Battlefield is a serene landscape, a stark contrast to the desperate fighting that once raged across its fields. Administered by the National Park Service, it encompasses key areas of the battle, including the Thomas and Worthington Farms, Best Farm, and portions of the historic roads and river crossings. Preservation efforts have aimed to restore the battlefield to its 1864 appearance as much as possible, despite the creeping encroachment of suburban development from nearby Frederick.

Visitors to Monocacy can walk the same ground where Union soldiers valiantly stood their ground. Interpretive signs and walking trails guide visitors through the key phases of the battle, telling the stories of the commanders and the common soldiers. The Visitor Center offers exhibits and a film that vividly portray the battle’s context and significance. Ranger-led programs provide deeper insights into the strategic importance of the site and the human cost of the conflict. The Best Farm, a historically significant property within the park, offers a glimpse into the agricultural life of the era and served as a Confederate field hospital during the battle.

Monocacy National Battlefield serves as a powerful reminder that not all pivotal battles are grand victories. Sometimes, the most profound impact comes from a delaying action, a stubborn defense against overwhelming odds. It is a testament to the courage of ordinary men under extraordinary pressure, and to a commander who, despite his personal military setbacks, understood the critical importance of his mission. In its quiet fields, Monocacy continues to whisper its vital lesson: that even in tactical defeat, strategic triumph can be forged, and that the sacrifice of a few can indeed save the many, securing the destiny of a nation. It is a battlefield that truly deserves to be remembered as the unsung stand that saved the capital.