The Unsung Visionary: George McJunkin and the Discovery that Rewrote American Prehistory

The windswept plains of northeastern New Mexico hold secrets as ancient as time itself, whispered through the arroyos and etched into the fossilized remains of long-extinct beasts. It was in this stark, beautiful landscape, over a century ago, that an unassuming cowboy with a keen eye and an unquenchable thirst for knowledge stumbled upon a discovery that would fundamentally rewrite the timeline of human presence in North America. His name was George McJunkin, and his story is one of profound observation, scientific revolution, and a belated recognition of an unsung hero whose intellectual curiosity transcended the formidable racial and educational barriers of his era.

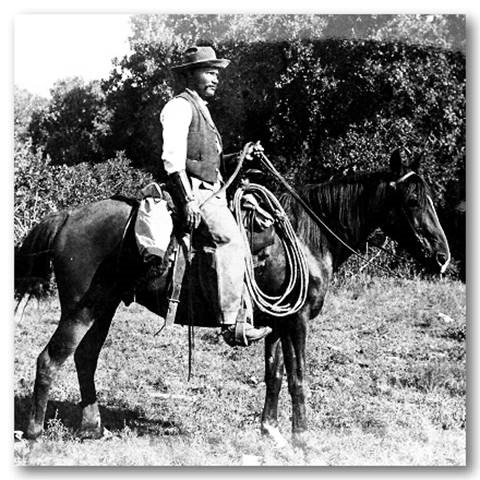

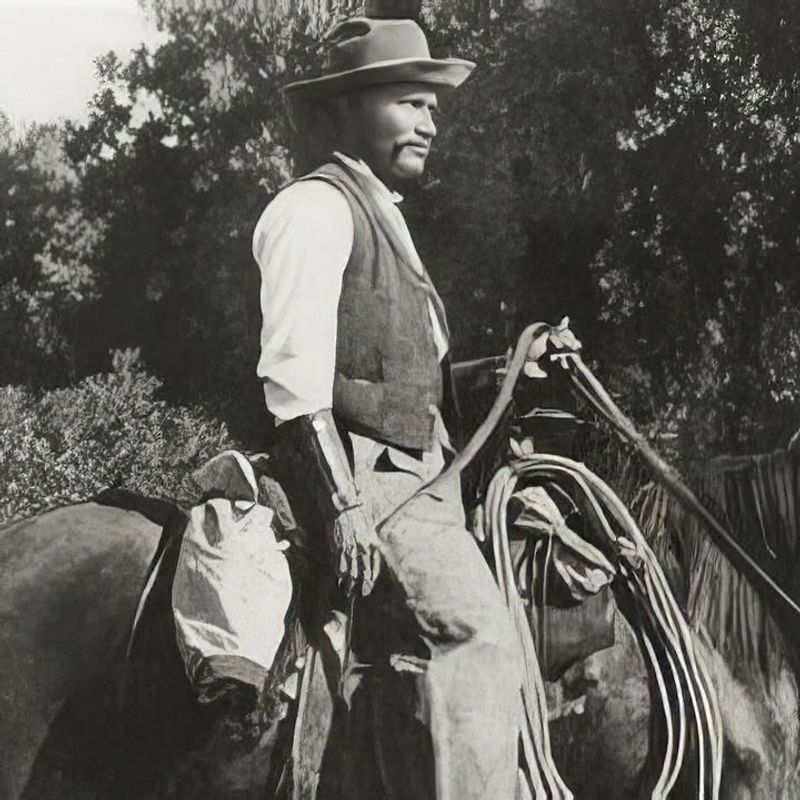

Born into slavery in Midway, Texas, in 1851, George McJunkin’s early life was defined by the harsh realities of a nation grappling with its moral failings. Emancipation in 1865, however, opened a new, albeit challenging, path for the young McJunkin. Like many freedmen of his generation, he sought opportunity and freedom in the burgeoning American West. He became a cowboy, a profession that demanded resilience, an intimate understanding of the land, and a mastery of practical skills. McJunkin excelled, his reputation growing as a skilled horseman, a crack shot, and an expert tracker. He learned to read and write, a remarkable feat for an African American in that period, and his self-education didn’t stop there. He devoured books, pouring over texts on geology, astronomy, and natural history, cultivating an intellect that far surpassed his formal schooling.

By the early 1900s, McJunkin had risen through the ranks to become the foreman of the vast Crowfoot Ranch near Folsom, New Mexico. It was a position of considerable responsibility and respect, a testament to his capabilities and character in an era when racial prejudice often dictated one’s station. His duties took him across thousands of acres, giving him an unparalleled familiarity with every ridge, gulch, and arroyo of the region. This deep connection to the land, combined with his voracious appetite for scientific understanding, set the stage for his momentous discovery.

The year was 1908. A torrential summer storm had unleashed a devastating flash flood through Wild Horse Arroyo, a dry creek bed that snaked across the ranch. The floodwaters, powerful and relentless, carved away layers of earth, exposing geological strata that had been hidden for millennia. As McJunkin rode out to assess the damage and mend fences, his eyes, trained by years of observation, caught something unusual. Scattered across the freshly exposed gully walls were bones – not the familiar remains of modern cattle or buffalo, but massive, ancient bones, unlike anything he had ever seen.

McJunkin immediately recognized their significance. He was no stranger to fossils; his self-taught knowledge of geology told him these bones belonged to creatures from a bygone age. But what truly captivated him, and what would prove to be the linchpin of his discovery, was their context. The bones were deeply embedded in a distinct geological layer, clearly undisturbed for an immense period. And, most importantly, alongside and even intermingled with these colossal bones, he observed crude, chipped stone tools and spear points.

He carefully collected some of these artifacts, bringing them back to the ranch. Over the next several years, McJunkin would periodically revisit the site, fascinated by its secrets. He understood, with an intuition that eluded many formally trained scientists of his day, that these stone implements were not merely coincidental. They were associated with the bones, indicating that humans had hunted these extinct giants. He spoke of his findings to anyone who would listen, showing off his collection of bones and spearheads, convinced that he had found evidence of ancient man in North America.

However, the prevailing scientific consensus of the early 20th century was a formidable barrier. The dominant archaeological paradigm held that humans had arrived in North America relatively recently, perhaps no more than 4,000 years ago, crossing the Bering land bridge at the end of the last Ice Age. The idea that humans could have coexisted with megafauna like the woolly mammoth or the ancient bison, long believed to have vanished before human arrival, was considered radical, even preposterous. Scientists, largely confined to their academic institutions, were slow to accept claims from amateur enthusiasts, especially those from an unlettered Black cowboy in rural New Mexico.

Despite McJunkin’s persistent efforts to bring his discovery to the attention of the wider scientific community, his pleas went largely unheard. He died in 1922, never knowing the true impact his observations would ultimately have. But the seeds of his discovery had been sown.

After McJunkin’s death, the site continued to intrigue local residents. Carl Schwachheim, a banker from Raton, New Mexico, who had seen McJunkin’s collection, became convinced of its importance. He contacted Harold Cook, a ranch owner and amateur paleontologist from Agate, Nebraska, who had a strong interest in ancient fauna. Cook, in turn, recognized the potential significance and reached out to Jesse Dade Figgins, the Director of the Denver Museum of Natural History (now the Denver Museum of Nature & Science).

Figgins, initially skeptical, dispatched a team to Wild Horse Arroyo in 1926. What they found began to chip away at the established scientific dogma. The team uncovered numerous bones of an extinct species of bison, Bison antiquus, a much larger ancestor of the modern buffalo. And then came the undeniable proof: a meticulously crafted, distinctive "fluted" spear point, clearly man-made, found in situ – still lodged between the ribs of one of the ancient bison skeletons, firmly encased in the same geological layer.

This was the smoking gun. It wasn’t just a bone and a tool found in the same vicinity; it was irrefutable evidence of a direct, fatal interaction between ancient humans and these long-extinct animals. The discovery sent shockwaves through the scientific community. Prominent paleontologists and archaeologists, many of whom had been staunch proponents of the "recent arrival" theory, flocked to Folsom to witness the evidence firsthand. Barnum Brown, the legendary "dinosaur hunter" from the American Museum of Natural History, arrived skeptical but left convinced. "The Folsom finds have put man back in America more than 10,000 years," he famously declared.

The Folsom site, as it came to be known, provided the first unambiguous evidence that humans had inhabited North America much earlier than previously believed, pushing back the timeline by at least 8,000 years to approximately 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. This discovery was revolutionary, establishing the existence of the "Folsom culture" and paving the way for further archaeological exploration that would eventually lead to the identification of the even older Clovis culture. It fundamentally reshaped our understanding of Paleo-Indians and their sophisticated hunting strategies, their adaptation to Ice Age environments, and their deep roots on the continent.

Yet, for decades, George McJunkin’s crucial role in this monumental discovery remained largely unacknowledged by the scientific establishment. His name was often omitted from initial reports and subsequent histories of the Folsom site. The credit, where it was given, typically went to the formally trained paleontologists and archaeologists who eventually validated his findings. This oversight was a stark reflection of the racial prejudices of the time and the tendency to disregard the contributions of "amateurs," particularly those from marginalized communities.

It has taken many years, and the diligent work of historians and archaeologists, to shine a light on McJunkin’s essential contribution. His story is a powerful reminder of the "hidden figures" in scientific discovery, individuals whose unique perspectives and keen observations are often overlooked due to societal biases. McJunkin’s lack of formal education did not diminish his intellectual capacity or his ability to interpret complex natural phenomena. His life embodies the spirit of the autodidact, a person driven by an innate curiosity to understand the world around them, often against immense odds.

Today, George McJunkin is rightfully celebrated as a pioneer. His legacy extends beyond the bones and spear points of Folsom. It is a testament to the power of observation, the importance of challenging established paradigms, and the enduring truth that scientific insight can emerge from the most unexpected places and from the most unexpected individuals. The Black cowboy who rode the New Mexico plains, tending cattle and gazing at the stars, ultimately saw deeper into the earth’s past than many of his learned contemporaries, forever altering our understanding of the human story on this continent. His unsung vision truly rewrote American prehistory, and his name now stands as a beacon for all who dare to look closer, question more, and trust their own keen perception.