The Unvanquished Spirit: A Global Chronicle of Colonial Resistance

Colonialism, a force that reshaped the world map and global power dynamics for centuries, often conjures images of dominant empires imposing their will. Yet, beneath the veneer of imperial control, a relentless and multifaceted resistance simmered, flared, and ultimately fractured the foundations of these seemingly insurmountable powers. From the initial European incursions to the eventual tides of decolonization, the story of colonial resistance is a testament to the indomitable human spirit, a complex tapestry woven with threads of defiance, sacrifice, ingenuity, and an unwavering quest for self-determination.

This resistance was rarely monolithic. It manifested in myriad forms: open warfare, political agitation, cultural preservation, economic boycotts, and subtle acts of everyday defiance. It was a continuous dialogue, often violent, between the colonizer and the colonized, shaping not only the destiny of nations but also the very concept of sovereignty and human rights. To understand the collapse of empires, one must first grasp the depth and persistence of the resistance that chipped away at their edifice.

The First Lines of Defense: Early Encounters and Armed Rebellion

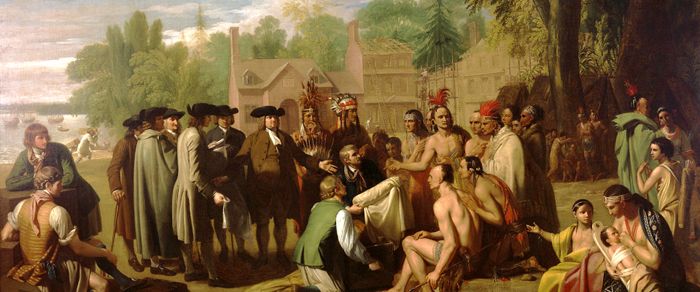

The arrival of European powers in the Americas, Africa, and Asia was rarely a peaceful affair. Indigenous populations, far from being passive recipients of foreign rule, often met these incursions with fierce resistance. In the Americas, figures like Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader, forged a pan-tribal confederacy in the early 19th century to resist American expansion, understanding that only unity could stand against the encroaching tide. His vision, though ultimately unsuccessful in halting the westward movement, highlighted the strategic foresight of indigenous leaders who recognized the existential threat posed by colonial ambitions.

Similarly, in Africa, early resistance often took the form of direct armed confrontation. Samory Touré, the Mandinka leader, built an impressive empire in West Africa in the late 19th century and waged a prolonged, sophisticated guerrilla war against the French for nearly two decades. His forces were well-organized, and he even established local arms factories to counter European technological superiority. His famous declaration, "I have fought against the white men because they have come to my country to spoil it," encapsulates the fundamental motivation for much early resistance: the defense of land, sovereignty, and way of life.

The Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, though ultimately a British victory, began with the stunning Zulu triumph at the Battle of Isandlwana, where spear-wielding warriors annihilated a technologically superior British force. This battle sent shockwaves through the British Empire, demonstrating that even the most advanced military could be humbled by a determined and strategically adept indigenous army. These early acts of defiance, though often leading to tragic outcomes for the resisting forces, served as powerful symbols, preserving a memory of independent existence and fueling future struggles.

The Spectrum of Resistance: From Mutiny to Satyagraha

As colonial powers consolidated their rule, resistance evolved. It moved beyond initial defensive wars to encompass a broader spectrum of tactics. One of the most significant early challenges to British rule in India was the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, also known as India’s First War of Independence. Triggered by a perceived insult to religious beliefs (greased cartridges for rifles), it rapidly escalated into a widespread rebellion involving not just soldiers but also princes, landlords, and peasants. While brutally suppressed, the Mutiny forced the British Crown to take direct control of India, ending the East India Company’s rule, and instilled a deep sense of national consciousness that would later blossom into a full-fledged independence movement.

In the 20th century, the rise of charismatic leaders and organized political movements marked a new phase. Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of Satyagraha, or non-violent civil disobedience, transformed the struggle for Indian independence and provided a blueprint for anti-colonial movements worldwide. His campaigns, such as the Salt March of 1930, where thousands defied the British salt tax by marching to the sea to make their own salt, were masterful acts of political theatre and moral suasion. Gandhi understood that by refusing to cooperate with unjust laws, the colonized could expose the moral bankruptcy of the colonizer, thereby undermining their legitimacy. As Gandhi famously stated, "First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win." His methods proved that moral force could be more potent than military might in achieving political change.

However, not all movements embraced non-violence. In Kenya, the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960) represented a violent struggle against British rule, fueled by land grievances and racial discrimination. Led primarily by the Kikuyu people, the Mau Mau engaged in guerrilla warfare, targeting both European settlers and African loyalists. The British responded with extreme brutality, including the use of concentration camps, torture, and mass detentions. While the Mau Mau were ultimately defeated militarily, their fierce resistance undeniably accelerated the pace of decolonization in Kenya and highlighted the desperate measures people would take to reclaim their land and freedom. The enduring legacy of Mau Mau is complex, often viewed as both a necessary, albeit violent, struggle for liberation and a dark chapter marked by internal divisions and atrocities.

Cultural and Intellectual Resistance: The Battle for Identity

Resistance was not confined to the battlefield or the political arena. Colonialism sought to impose not just political and economic control but also cultural hegemony, often disparaging indigenous languages, religions, and customs. In response, a powerful current of cultural and intellectual resistance emerged. Writers, poets, artists, and scholars became vital agents of defiance, reclaiming their narratives and celebrating their heritage.

The Harlem Renaissance in the United States, while not strictly anti-colonial in the traditional sense, saw African American artists and intellectuals assert their cultural identity and challenge racial oppression, inspiring similar movements globally. In the French-speaking world, the Négritude movement, spearheaded by figures like Aimé Césaire from Martinique and Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal, sought to affirm Black identity and values, rejecting colonial assimilation and celebrating African heritage. Césaire’s powerful work, "Discourse on Colonialism," remains a searing indictment of imperial exploitation and dehumanization.

Language itself became a battleground. Many colonial powers attempted to suppress indigenous languages in favor of their own, viewing them as obstacles to progress. Yet, the persistence of local languages, often taught in secret or kept alive through oral traditions, served as a crucial form of resistance, preserving cultural memory and identity. The establishment of independent schools and religious institutions, sometimes clandestine, also played a vital role in safeguarding indigenous knowledge systems and values against colonial encroachment.

Global Solidarity and the Tides of Decolonization

The mid-20th century witnessed a dramatic acceleration of anti-colonial movements, fueled by the weakening of European powers after two World Wars and the rising tide of self-determination. The Bandung Conference of 1955, bringing together leaders from newly independent Asian and African nations, was a landmark event. It symbolized a new era of Afro-Asian solidarity and articulated a collective rejection of colonialism and Cold War alignments. Leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru of India, Sukarno of Indonesia, and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana championed the cause of the unaligned, giving a powerful voice to the aspirations of the colonized world.

In Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh masterfully fused nationalist fervor with communist ideology, leading a decades-long struggle first against French colonial rule and then against American intervention. His declaration of independence in 1945, echoing the American and French revolutions, asserted Vietnam’s right to self-determination, stating, "All men are created equal; they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness." The eventual Vietnamese victory against the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 was a pivotal moment, signaling the irreversible decline of European colonialism in Southeast Asia.

Even in settler colonies, where the path to independence was often more protracted and violent, resistance ultimately prevailed. In South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC), though initially founded on non-violent principles, eventually embraced armed struggle under leaders like Nelson Mandela to dismantle the apartheid regime, a particularly brutal form of internal colonialism. Mandela’s 27 years in prison became a symbol of unwavering resistance, and his eventual release and the dismantling of apartheid in 1994 marked a triumph for human rights and self-determination on a global scale.

The Enduring Legacy of Resistance

The legacy of colonial resistance is profound and far-reaching. It not only led to the dismantling of vast empires but also fundamentally reshaped international law, the concept of human rights, and the global political order. The voices of those who resisted, once marginalized, are now increasingly central to our understanding of history.

However, the end of formal colonialism did not erase its impact. Many post-colonial nations continue to grapple with borders drawn by imperial powers, economic dependencies, and the lingering effects of cultural subjugation. Yet, the spirit of resistance continues, evolving to confront new forms of neo-colonialism, economic exploitation, and environmental injustice.

The story of colonial resistance is a powerful reminder that power, even when seemingly absolute, is always contested. It is a chronicle of courage against overwhelming odds, of the unwavering belief in the right to freedom and dignity. From the ancient warriors defending their ancestral lands to the modern activists advocating for justice, the unvanquished spirit of those who resisted colonialism continues to inspire, reminding us that the pursuit of self-determination is a timeless and universal human endeavor. It is a vital narrative that ensures the history of empire is never told solely from the perspective of the conqueror.