The Unwritten Chapters: Unearthing America’s Layered Legends

America, a land forged in grand narratives and epic struggles, pulses with a rich tapestry of legends. From the towering lumberjack Paul Bunyan and his blue ox, Babe, shaping the very landscape, to the spectral headless horseman haunting Sleepy Hollow, these tales form the bedrock of a shared cultural identity. Yet, beneath the whimsical and the heroic, lie deeper, often darker, legends – stories born of conflict, displacement, and the clash of civilizations that have profoundly shaped the nation. These are not merely fanciful fables, but the unwritten chapters of history, imbued with the enduring power of myth and memory, none more poignant and instructive than the tragic saga of the Ute War in Colorado.

At first glance, American legends seem straightforward. They speak of boundless possibility, of rugged individualism conquering the wilderness. Paul Bunyan, a figure of superhuman strength and industry, symbolizes the conquering spirit of American expansion, his axe clearing forests for settlers and his footsteps forming lakes. Johnny Appleseed, the gentle pioneer John Chapman, embodies the spirit of nurturing and settlement, scattering seeds of sustenance across the burgeoning frontier. These are the foundational myths, designed to inspire, to simplify, and to unify a nascent nation.

Then there are the legends born of the Wild West – figures like Jesse James, Billy the Kid, and Wyatt Earp. These are more complex, straddling the line between outlaw and hero, their stories reflecting a turbulent era of lawlessness, justice, and the often-blurred morality of the frontier. They speak to a primal fascination with freedom, rebellion, and the quest for order in a chaotic world. Their legends are shaped by dime novels and campfire tales, transforming ordinary men into archetypes of American grit and defiance.

But as the nation expanded, these pioneering myths often collided with the ancient narratives of the indigenous peoples who already inhabited the land. The legends of Native American tribes – their creation stories, their animal spirits, their tales of ancestral heroes – speak of a profound connection to the earth, a cyclical understanding of time, and a spiritual reverence for nature that often stood in stark contrast to the European newcomers’ drive for ownership and extraction. These are legends that, for too long, were marginalized or ignored in the dominant national discourse, yet they hold vital keys to understanding the true, complex history of America.

It is in this fraught intersection of cultures, ambitions, and conflicting worldviews that the Ute War of Colorado emerges not just as a historical event, but as a searing legend – a powerful, painful narrative that continues to resonate through the landscape and the collective memory of the West. It is a legend of broken promises, cultural misunderstanding, and the relentless march of "progress" that forever altered the lives of the Nuche, the Ute people.

The Ute: Guardians of a Mountain Kingdom

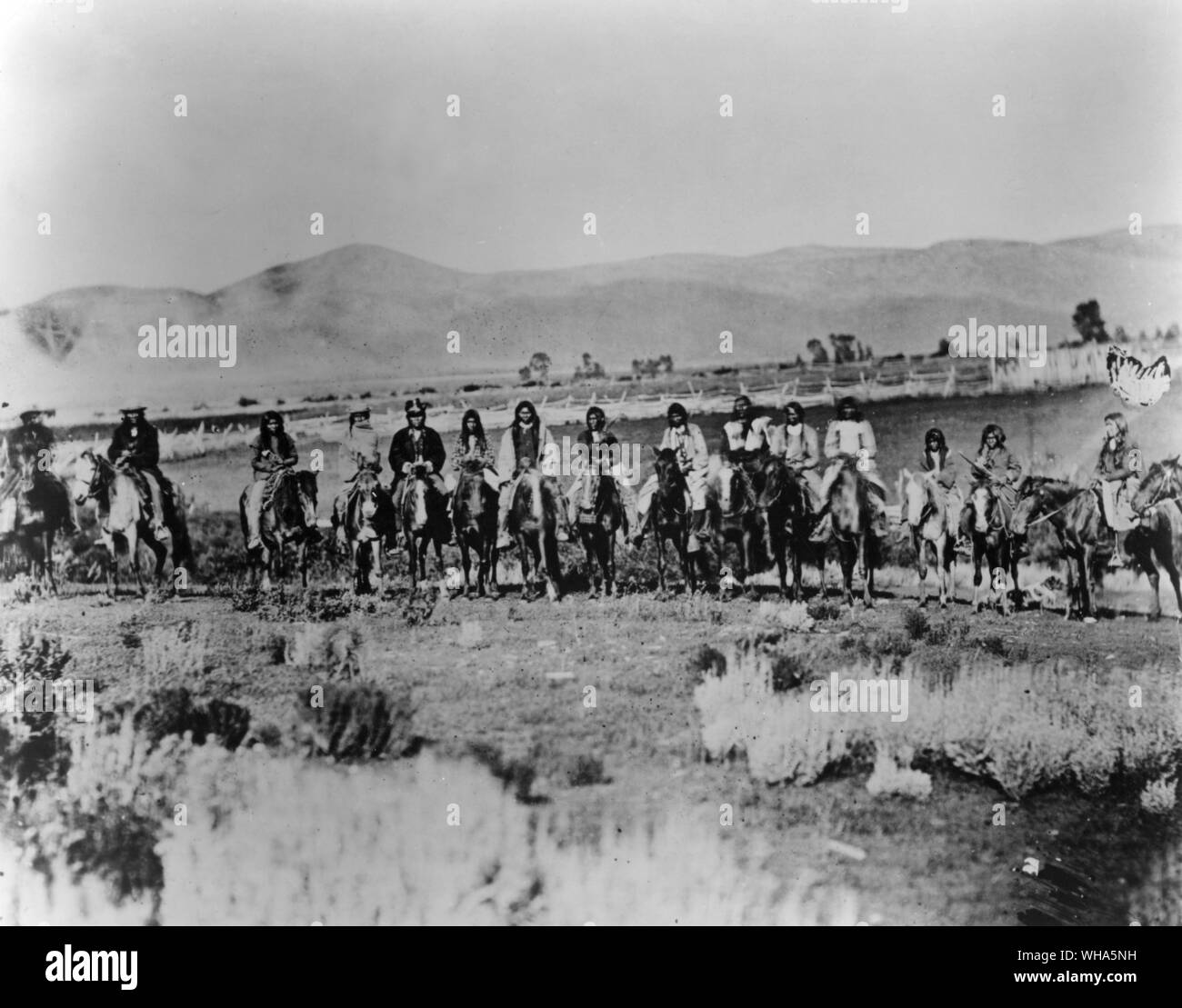

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Ute people were the undisputed masters of a vast domain stretching across what is now Colorado, Utah, and parts of New Mexico. They were skilled hunters, horsemen, and warriors, intimately connected to the rhythm of the mountains and valleys. Their legends spoke of the Creator, of the deer and the bear, and of a deep spiritual bond with the land that sustained them. For centuries, they had navigated the challenges of their environment, developing a rich culture adapted to the demanding Rocky Mountain terrain.

The mid-19th century brought a seismic shift. The discovery of gold and silver in Colorado ignited a stampede of prospectors and settlers, an insatiable wave of humanity driven by Manifest Destiny – the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstanding, steadily eroded Ute lands. By the 1870s, the once-expansive Ute territory had been whittled down to a fraction, primarily concentrated on reservations in western Colorado.

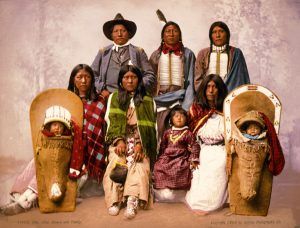

One of the most significant figures in this unfolding drama was Chief Ouray, a sagacious and remarkably intelligent leader of the Uncompahgre Ute. Ouray, born of a Ute mother and a Jicarilla Apache father, was fluent in several languages, including English and Spanish. He understood the overwhelming power of the encroaching white world and believed the only path to survival for his people lay in diplomacy and adaptation. He tirelessly advocated for his people’s rights, traveling to Washington D.C. multiple times to negotiate with presidents and politicians. His efforts, however, were often met with indifference or outright deceit. As historian Peter Cozzens noted in The Earth is Weeping, "Ouray walked a tightrope, trying to preserve what he could for his people while navigating the treacherous currents of American expansion."

The Seeds of Conflict: Meeker’s Vision and Ute Resistance

The stage for tragedy was set in 1878 with the appointment of Nathan C. Meeker as the Indian Agent for the White River Ute Reservation. Meeker was a former journalist, a utopian idealist, and a founder of the Union Colony (later Greeley, Colorado). He harbored a rigid vision for the Ute: they must abandon their nomadic hunting lifestyle, become Christian farmers, and adopt "civilized" ways, all within a generation. He saw their traditions not as a rich cultural heritage, but as an obstacle to progress.

Meeker’s policies were immediately confrontational. He demanded the Utes plow their land for farming, despite it being unsuitable for agriculture and against their cultural practices. He curtailed their traditional hunting rights, confiscated their horses, and even insisted on plowing a Ute horse racing track, a site of cultural importance and recreation, to plant potatoes. This act, more than any other, symbolized the profound disrespect Meeker held for Ute traditions and autonomy. The Utes, already frustrated by broken treaties and the encroachment of settlers, saw these actions as direct assaults on their way of life.

Tensions escalated rapidly. The Utes, particularly the young men, grew increasingly defiant, refusing to submit to Meeker’s dictates. Meeker, in turn, grew frustrated and fearful, perceiving Ute resistance as insolence and a threat. He requested military intervention, claiming the Utes were hostile and ungovernable.

The Cataclysm: Meeker Massacre and Thornburgh Ambush

On September 29, 1879, the simmering conflict erupted into full-blown war. Major Thomas T. Thornburgh, commanding a column of 175 soldiers from Fort Fred Steele, Wyoming, was en route to the White River Agency, ostensibly to restore order. The Utes, led by figures like Chief Jack and Chief Colorow, viewed the approaching soldiers as an invasion, a violation of their treaty rights that stipulated no soldiers were to enter the reservation without their consent.

As Thornburgh’s column entered a canyon near Milk Creek, about 18 miles from the agency, they were ambushed by Ute warriors. The ensuing battle was fierce. Major Thornburgh and 13 of his men were killed, and many more wounded. The surviving soldiers dug in, creating a defensive perimeter, and endured a siege that lasted for several days until reinforcements arrived.

Simultaneously, at the White River Agency, another tragedy unfolded. Ute warriors, enraged by the invasion and the escalating conflict, attacked the agency. Nathan Meeker and ten of his employees were killed, their bodies mutilated. Meeker’s wife, daughter, and other women and children were taken captive, enduring weeks of harrowing captivity before being released through the tireless diplomatic efforts of Chief Ouray and his wife, Chipeta.

The Aftermath: Removal and a Scarred Landscape

The "Meeker Massacre" and "Thornburgh Ambush," as they became known in the American press, ignited a firestorm of public outrage across the nation. Newspapers screamed for vengeance, demanding the complete removal of the Utes from Colorado. "The Utes Must Go!" became a rallying cry.

Despite Chief Ouray’s continued efforts to explain the Ute perspective and negotiate a peaceful resolution, the political will was overwhelming. The Ute people, scapegoated for the violence and deemed an obstacle to further settlement and resource extraction (especially after valuable coal deposits were discovered on their lands), were doomed.

In 1881, under the terms of a new agreement, the Utes were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands in western Colorado. The Uncompahgre and White River Utes were relocated to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in northeastern Utah. The Southern Utes were confined to a narrow strip of land in southwestern Colorado, forming what are now the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute Reservations. The move was devastating, a catastrophic blow to their culture, economy, and spiritual connection to their homeland. Many died during the arduous journey or in the harsh new environments.

The Legend Endures: A Legacy of Contradictory Truths

The Ute War is more than just a historical event; it is a profound American legend, embodying the nation’s complex and often contradictory truths. For many settlers and their descendants, it became a legend of heroic pioneers facing savage Indians, a justification for the relentless expansion and the "taming" of the West. For the Ute people, it is a legend of profound betrayal, a testament to their ancestors’ struggle to preserve their identity and way of life against overwhelming odds. It is a legend etched into their oral traditions, their ceremonies, and their very being.

This legend of the Ute War serves as a powerful reminder that American legends are rarely monolithic. They are often layered, fractured, and fiercely contested, reflecting different perspectives and experiences. It highlights the devastating human cost of Manifest Destiny and the often-unacknowledged sacrifices made by indigenous peoples in the forging of the United States.

Today, the lands of western Colorado still whisper tales of the Ute War. The mountains stand as silent witnesses to the Ute’s ancient dominion, the rivers flow over ground once soaked in blood and tears. The descendants of the Ute people carry the memory of the war, a living legend that informs their present struggles for sovereignty, cultural preservation, and justice.

America’s legends, from the fantastical to the historical, are the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and where we came from. But to truly understand the nation, we must engage with all of them – not just the comforting myths of expansion and heroism, but also the difficult, uncomfortable legends like the Ute War. Only by acknowledging these unwritten chapters, by listening to the voices of all who shaped this land, can we begin to grasp the full, rich, and undeniably complex tapestry of American identity. The legends of America are not just about the past; they are about understanding the present and building a more just future.