The Valley Ablaze: Sheridan’s Scorched Earth Triumph in the Shenandoah

Autumn 1864. The Shenandoah Valley, Virginia’s verdant breadbasket and a vital artery for the Confederacy, was about to be put to the torch. For three long years, this picturesque region had served as both a strategic invasion route into the Union heartland and a seemingly inexhaustible larder for the Southern armies. But a new, relentless force was now unleashed upon it: Major General Philip Henry Sheridan, a compact, aggressive cavalryman, given a singular, brutal mandate by Ulysses S. Grant: neutralize the Valley, utterly and permanently.

What followed was a campaign of unprecedented ferocity and systematic destruction, a pivotal turning point that showcased the grim reality of "total war" and effectively sealed the fate of the Confederacy. It was a campaign not merely of battles won, but of resources obliterated, morale shattered, and a landscape transformed into a wasteland, ensuring that, as Sheridan famously declared, "a crow flying over the Valley would have to carry its own rations."

The Strategic Imperative: Grant’s Frustration and a New Vision

By the summer of 1864, the Union war effort, despite Grant’s relentless Overland Campaign, seemed bogged down. Jubal Early’s audacious raid on Washington D.C. in July had sent shivers through the Union capital, underscoring the enduring threat posed by Confederate forces operating out of the Shenandoah. Grant, weary of the Valley’s perennial role as a sanctuary and staging ground for Southern incursions, realized a change in strategy was imperative. He needed someone ruthless, efficient, and utterly dedicated to the task. His choice fell on Sheridan, a man whose meteoric rise was fueled by his aggressive tactics and unwavering loyalty.

Grant’s orders to Sheridan were chillingly clear. Beyond simply defeating Early’s Army of the Valley, Sheridan was to "eat out Virginia clean and clear as a hound’s tooth," to "waste the country in the Shenandoah Valley so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their provender with them." This was not just military engagement; it was economic warfare designed to cripple the Confederacy’s ability to feed its armies and sustain its fight. The Valley, a region that had contributed an estimated 25% of the Confederacy’s wheat harvest, was to be rendered useless.

Sheridan Takes Command: The Army of the Shenandoah

Sheridan, only 33, took command of the newly formed Army of the Shenandoah, a formidable force numbering nearly 40,000 men. Facing him was Lieutenant General Jubal Early, a seasoned, albeit often outnumbered, Confederate commander known for his tenacity and his ability to exploit the Valley’s terrain. For weeks, the two armies maneuvered cautiously, Sheridan biding his time, consolidating his forces, and gathering intelligence, while Early, ever the opportunist, sought to gauge his opponent’s temperament.

The waiting game ended on September 19, 1864, with the Battle of Opequon, also known as the Third Battle of Winchester. Early’s forces were positioned just outside Winchester, a town that had changed hands dozens of times throughout the war. Sheridan launched a massive, coordinated assault, utilizing his superior numbers and cavalry effectively. The battle raged for hours, characterized by fierce fighting, particularly on the Union left flank. Sheridan, riding across the battlefield, personally rallied his troops, his presence an electrifying force.

Despite initial Confederate resistance, the weight of the Union assault proved overwhelming. A decisive cavalry charge led by Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer and Wesley Merritt shattered Early’s left flank, turning a bloody stalemate into a rout. Early’s army was sent reeling, suffering over 5,000 casualties to the Union’s 4,000. It was a crucial Union victory, the first major blow to Early’s command in the Valley, and it opened the door for Sheridan to pursue his relentless mission.

Fisher’s Hill and "The Burning": The Valley Laid Waste

Three days later, on September 22, Sheridan pressed his advantage. Early had attempted to establish a defensive line at Fisher’s Hill, a strong natural position south of Strasburg, hoping to check the Union advance. However, Sheridan, with his characteristic aggressiveness, once again outmaneuvered him. While a frontal assault occupied Early’s attention, a flanking movement led by Maj. Gen. George Crook’s VIII Corps stealthily advanced through dense woods, striking the Confederate left. The surprise attack crumbled Early’s lines, sending his already battered army into another headlong retreat. The Union captured over 1,000 prisoners and 12 cannon, effectively completing the military phase of the campaign to eliminate Early as a significant threat.

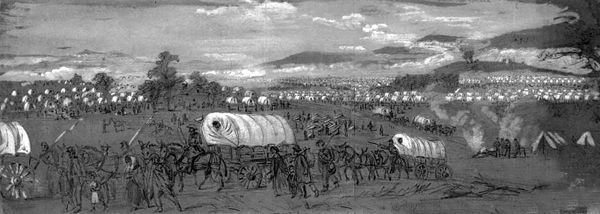

With Early’s army shattered and in disarray, Sheridan turned his attention to the second, more brutal part of his mission: the systematic destruction of the Valley’s agricultural capacity. From September 26 to October 8, a period chillingly known as "The Burning," Sheridan’s troops marched slowly north through the Valley, leaving a swathe of devastation in their wake.

This was not indiscriminate looting, though that undoubtedly occurred. This was a calculated, military operation. Cavalry detachments, often preceded by scouts, went from farm to farm, systematically destroying anything that could aid the Confederate war effort. Barns filled with hay and grain were set ablaze, mills used for grinding flour were dismantled or burned, and thousands of livestock—cattle, sheep, hogs—were either confiscated for Union rations or killed. Fences were torn down, fields were trampled, and even farm implements were often broken.

The human cost was immense. Thousands of civilians, mostly women, children, and the elderly, were left without food, shelter, or the means to survive the coming winter. Their pleas and protests were largely ignored by the Union soldiers, who were simply following orders. One Union soldier, reflecting on the grim task, wrote, "It was a sad sight to see the people standing by the road and see their barns and houses burning." Yet, for Sheridan and Grant, the strategic imperative outweighed humanitarian concerns. The goal was to render the Valley incapable of sustaining a hostile army, and in that, they were chillingly successful. The smoke from the burning barns and mills reportedly darkened the sky for days, visible for miles.

Cedar Creek: A Surprise Attack and Sheridan’s Ride

Just as the Union leadership believed the Valley campaign was drawing to a close, Jubal Early, ever the defiant spirit, launched one last, desperate gamble. On October 19, 1864, under the cover of a dense fog and darkness, Early’s forces launched a daring surprise attack on the sleeping Union camps along Cedar Creek. The assault was devastatingly effective. Union troops, caught completely off guard, broke and fled in panic. By dawn, Early had pushed the Union line back miles, capturing artillery and thousands of prisoners. It appeared to be a stunning Confederate victory, threatening to undo all of Sheridan’s previous successes.

However, Sheridan himself was not on the battlefield. He had been attending a conference in Washington D.C. and was returning to his command, having spent the night in Winchester, approximately 20 miles north of the battle. Waking to the sounds of distant cannon fire, he quickly grasped the gravity of the situation. Mounting his magnificent black charger, Rienzi (later renamed Winchester), Sheridan rode south at a furious pace.

His ride, immortalized in poetry and legend, was a pivotal moment. As he galloped along the Valley Pike, he encountered streams of retreating, demoralized Union soldiers. "Face the other way, boys! We’re going back!" he shouted, his small but powerful figure inspiring renewed hope. His mere presence, his calm demeanor, and his booming voice instilled courage in the shattered ranks. He rallied regiments, reformed lines, and personally led a counterattack.

By early afternoon, the tide had turned. Early’s forces, exhausted and disorganized by their morning’s success and laden with captured Union supplies, were unable to withstand Sheridan’s resurgent army. The Union counterattack, spearheaded by Sheridan’s fiery leadership, routed the Confederates completely. Early’s army suffered heavy casualties and lost nearly all of its remaining artillery. Cedar Creek was not just a Union victory; it was a devastating, irreversible defeat for Early and the Confederacy in the Valley.

The Aftermath and Legacy: A Harsh Victory

The victory at Cedar Creek effectively ended the Shenandoah Valley as a significant theater of the Civil War. Early’s army was shattered beyond repair and ceased to be an offensive threat. The strategic objectives of the campaign had been achieved: Washington D.C. was secure, the Confederacy’s "breadbasket" was destroyed, and a vital invasion route was sealed off.

The psychological impact was profound. For the Union, Sheridan’s victories, especially the dramatic turnaround at Cedar Creek, provided a much-needed boost in morale and significantly aided President Lincoln’s re-election chances in November 1864, demonstrating that the war was winnable. For the Confederacy, the loss of the Valley was a crippling blow, both materially and psychologically. It signified the relentless tightening of the Union’s grip and the effectiveness of Grant’s total war strategy.

Sheridan’s Valley Campaigns were a brutal testament to the evolving nature of warfare. They showcased the effectiveness of combined arms tactics, the importance of aggressive leadership, and the devastating power of economic warfare. The "Burning" remains a controversial chapter, highlighting the grim reality that victory in total war often comes at an immense cost to civilian populations. Yet, for Grant and Lincoln, it was a necessary evil, a harsh but effective means to hasten the end of a bloody conflict.

By late 1864, the Shenandoah Valley, once a symbol of Confederate resilience and abundance, lay desolate and broken. Its fertile fields were barren, its barns reduced to ashes, and its people scarred by the harsh reality of war. Sheridan’s campaign was a masterclass in military efficiency, a stark reminder that in the crucible of civil war, even the most picturesque landscapes could become battlegrounds for the soul of a nation, forever marked by fire and the relentless march of a determined general.