The Vanishing Echo: Unearthing the Story of Florida’s Acuera Tribe

In the verdant heart of central Florida, where ancient live oaks drip with Spanish moss and the earth holds secrets beneath its sandy soil, lies the largely forgotten narrative of the Acuera people. They were a vibrant, resilient, and fiercely independent tribe, one of the many indigenous groups that thrived in the peninsula long before the arrival of European sails. Their story, a poignant blend of cultural richness, courageous resistance, and tragic decline, serves as a stark reminder of the profound human cost of colonialism and the enduring power of a people’s will to survive against impossible odds.

Today, the Acuera are not just a footnote in history; they are an echo, a whisper in the wind that once carried the sounds of their villages, their ceremonies, and their defiant cries against invaders. To unearth their story is to reconstruct a mosaic from fragmented historical records, archaeological findings, and the silent testimony of the land itself.

A Flourishing World: Acuera Before Contact

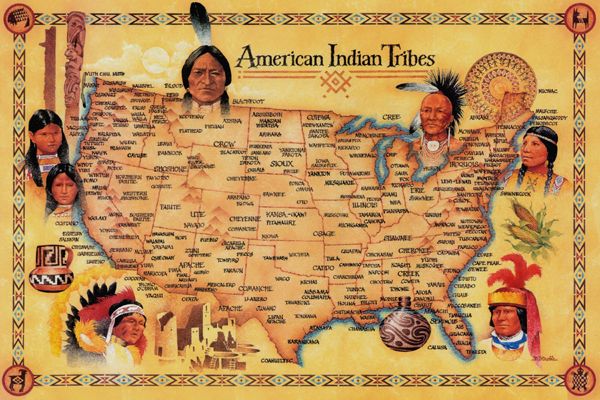

Before the 16th century, the Acuera occupied a significant territory centered around what is now Marion County, Florida, extending into parts of Lake and Sumter counties. Their lands, watered by numerous lakes, rivers, and springs, including the Ocklawaha River basin and areas near Lake Weir, provided an abundance that fostered a sophisticated and settled lifestyle. They were part of the broader Timucuan language family, a vast network of chiefdoms that dominated much of northern and central Florida.

The Acuera were primarily an agricultural people, their sustenance rooted in the cultivation of maize, beans, and squash. This agrarian base was supplemented by skillful hunting of deer, bear, and smaller game, as well as fishing in the rich waterways that crisscrossed their territory. Their villages were typically situated near water sources, often fortified with palisades, reflecting a need for defense even among neighboring tribes. Within these settlements, life revolved around community, family, and a deeply spiritual connection to the land.

"They lived in well-ordered villages, often around a central plaza," explains Dr. William Jones, a historian specializing in Florida’s indigenous past. "Their social structure was hierarchical, led by a chief, or cacique, who held significant spiritual and political authority. These weren’t nomadic bands; they were established societies with complex social rules, trade networks, and a rich oral tradition." Archaeological digs have revealed remnants of their pottery, tools, and burial mounds, painting a picture of a people skilled in craftsmanship and possessing a reverence for their ancestors and the spiritual realm. Their vibrant culture, however, was on the precipice of an irreversible collision.

The Shadow of Sails: First Encounters and Fierce Resistance

The first ripples of European presence reached Florida’s shores in 1513 with Juan Ponce de León. While his initial contact was with coastal tribes, it marked the beginning of a new era. For the Acuera, the true turning point came in 1539 with the arrival of Hernando de Soto’s expedition. De Soto, a veteran of the Pizarro conquest of Peru, landed in Florida with an insatiable hunger for gold and a brutal methodology for obtaining it. His expedition cut a path of destruction across the Southeast, forever altering the landscape and its native inhabitants.

The Acuera, unlike some coastal groups already weakened by earlier encounters or disease, met De Soto with an unyielding spirit. Spanish chroniclers, whose accounts often painted indigenous peoples as either docile or savage, noted the Acuera’s exceptional bravery and fierce demeanor. De Soto’s expedition, numbering hundreds of soldiers, priests, and enslaved Africans, along with horses, pigs, and war dogs, represented an overwhelming force. Yet, the Acuera refused to be easily subdued.

"The Acuera were known for their tenacious resistance," states a translated passage from the Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto in the Conquest of Florida. "They would not yield their villages or their stores of maize without a fight, inflicting casualties upon our men and retreating into the dense forests to wage guerrilla warfare." De Soto’s men eventually reached Acuera territory, demanding provisions, guides, and women, often met with arrows rather than compliance. Their chief, named Acuera by the Spanish, reportedly defied De Soto’s demands, stating that he would not "send him women for concubines, nor men for servants, but that he would send him back a head if he came into his country." This defiance, a powerful statement of sovereignty, characterized their initial interactions.

The Spanish, despite their superior weaponry, found the Acuera a formidable opponent. They were skilled archers and masters of their terrain, using the dense forests and swamps to their advantage. However, the sheer force and technological superiority of the Spanish, combined with the devastating, invisible enemy they carried – European diseases – began to take their toll.

A Century of Attrition: Missions, Disease, and War

Following De Soto’s destructive passage, the Acuera, like many other Florida tribes, faced a relentless onslaught on multiple fronts. The Spanish, after several failed attempts, established a permanent presence in Florida with the founding of St. Augustine in 1565. This ushered in the era of the mission system, a dual strategy of religious conversion and political control.

For the Acuera, located further inland, the full force of the mission system came later than for coastal groups. However, by the early 17th century, Franciscan friars began establishing missions within or near Acuera territory, such as San Luis de Acuera. These missions aimed to "civilize" and Christianize the native population, but their true impact was far more insidious. They fundamentally disrupted traditional social structures, forced cultural assimilation, and, most catastrophically, became centers for the spread of Old World diseases.

Smallpox, measles, influenza, and other pathogens, against which Native Americans had no immunity, swept through the indigenous populations with terrifying speed and lethality. Villages that had once numbered in the thousands were reduced to mere hundreds, sometimes within months. "It is impossible to overstate the impact of disease," says Dr. Jones. "Estimates suggest that 70-90% of Florida’s native population perished from disease alone within a century of European contact. This wasn’t just a loss of life; it was a collapse of entire societies, a demographic catastrophe that few cultures could ever recover from."

Compounding the demographic collapse were continued cycles of violence. The Spanish engaged in punitive raids against tribes that resisted conversion or control. They also exacerbated existing inter-tribal rivalries, often arming some groups against others, creating a volatile landscape of perpetual conflict. The Acuera, once a powerful chiefdom, found their numbers dwindling, their political cohesion fractured, and their traditional ways of life under siege. Many were enslaved and sent to labor in the Caribbean or the Spanish mines, further depleting their ranks.

By the late 17th century, the remnants of the Acuera were caught in a brutal pincer movement. From the north, English-backed Creek and Yamasee raiders, armed with firearms, launched devastating slave raids into Spanish Florida. From the east, Spanish authorities continued to press for control and conversion. The few remaining Acuera either sought refuge within the mission system, only to face disease and cultural dissolution, or fled into the deep interior, attempting to merge with other shattered remnants of Timucuan or Oconee groups.

The Fading Echoes: Disappearance and Legacy

By the early 18th century, the Acuera, as a distinct cultural and political entity, had effectively vanished. The few survivors were absorbed into the emerging Seminole confederacy, a diverse group formed from the remnants of Florida’s indigenous peoples and Creek migrants from Georgia, or they simply succumbed to the relentless pressures of disease, warfare, and cultural annihilation. The once-vibrant Acuera chiefdom, with its rich traditions and fierce independence, became little more than a memory, preserved only in the dry prose of Spanish colonial documents and the faint traces in the earth.

The story of the Acuera is a poignant example of the fate that befell countless indigenous groups across the Americas. Their disappearance wasn’t a natural evolution but a catastrophic erasure, a direct consequence of colonial expansion. Yet, their legacy, though subtle, endures. The land they inhabited still bears the imprint of their presence; archaeological sites continue to yield clues about their daily lives, their beliefs, and their resilience. The very name "Acuera," possibly meaning "fire" or "swift" in their language, resonates with the spirit of a people who fought valiantly for their homeland and their way of life.

Today, as Florida continues to grapple with its complex history, the Acuera serve as a powerful reminder of what was lost. Their story compels us to look beyond the dominant narratives and to acknowledge the vibrant, diverse indigenous cultures that thrived here for millennia. It is a call to remember the human cost of empire, to respect the memory of those who resisted, and to understand that the echoes of their past continue to shape the present, urging us to listen more closely to the whispers from the land. The Acuera may be gone, but their spirit of defiance and their profound connection to Florida’s heartland remain, an indelible part of the Sunshine State’s untold story.