The Veins of Fortune and Folly: Unearthing Southwestern Colorado’s Mining Legacy

The crisp, thin air of the San Juan Mountains today whispers tales of grandeur and grit, of fortunes won and lost, echoing through the majestic canyons and high-altitude passes. For modern travelers tracing the scenic San Juan Skyway, the breathtaking vistas of jagged peaks, alpine meadows, and cascading waterfalls are a testament to nature’s raw beauty. Yet, beneath this serene facade lies a history forged in pickaxes and dynamite, a saga of early southwestern Colorado mining that transformed a rugged wilderness into a crucible of human ambition, resilience, and often, despair.

This wasn’t merely a gold rush; it was a silver rush, a copper rush, a lead rush – a fevered pursuit of subterranean wealth that lured tens of thousands to one of America’s most unforgiving landscapes. From the mid-19th century through the early 20th, the San Juans became a magnet for dreamers, engineers, entrepreneurs, and outlaws, all driven by the promise of riches hidden deep within the earth.

The First Whispers of Gold: Challenging a Wilderness

Before the grand stampede, the San Juan Mountains were largely the domain of the Ute people, who had revered and roamed these lands for centuries. Their ancient trails, often following game paths, would later become the treacherous routes for prospectors. The first significant mineral discoveries in southwestern Colorado are generally credited to the Baker Expedition of 1860, which ventured into what is now Baker’s Park (near modern-day Silverton). Though their initial gold finds were modest and the venture quickly dissolved due to harsh conditions and Ute resistance, the seed of possibility had been planted.

The Civil War temporarily diverted attention, but by the late 1860s and early 1870s, prospectors, often veterans of earlier rushes, began to trickle back. These were men and a few hardy women of extraordinary resolve. They faced not just the elements – blizzards that could bury cabins for weeks, rockslides, and the constant threat of hypothermia at elevations often exceeding 10,000 feet – but also the very real danger of starvation, injury, and isolation. Transportation was rudimentary, relying on pack mules or the miners’ own backs, hauling supplies over passes still choked with snow in July.

"Every swing of the pick is a prayer, every glimpse of color a fleeting hope," one anonymous prospector supposedly scrawled into his diary during those early, lean years. This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the blend of desperation and optimism that fueled the initial push into the San Juans.

From Placer to Lode: The Shift to Hard Rock

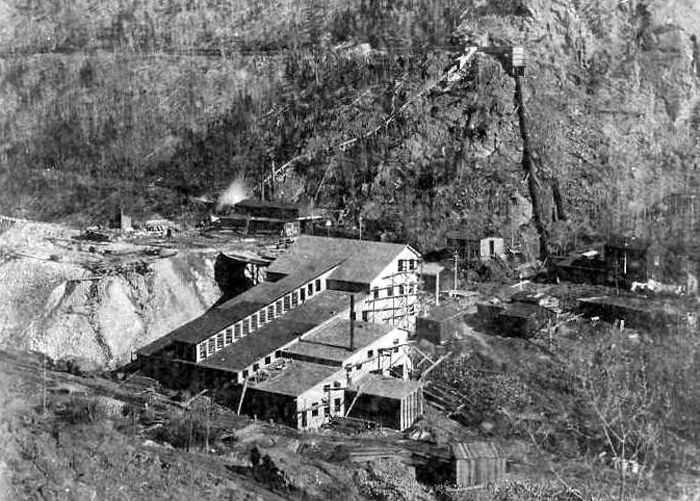

Initially, the focus was on placer mining – sifting gold from stream beds. But the true wealth of the San Juans lay not in the surface gravels but in the hard rock veins, deep within the mountains. This shift from placer to lode mining marked a turning point, demanding greater capital, advanced engineering, and a more organized approach. It also meant a transition from individual prospectors to mining companies.

The discovery of rich silver veins in the early 1870s, particularly around what would become Silverton and Ouray, sparked the true boom. The San Juan mining district officially opened in 1873 after a treaty with the Utes ceded a large tract of their ancestral lands, an agreement often seen as coerced and devastating for the indigenous population. This treaty, while opening the door for miners, simultaneously closed it on the Ute way of life, leading to further displacement and conflict.

Towns Forged in Ore: Silverton, Ouray, and Telluride

Suddenly, the remote mountain valleys pulsed with life. Silverton, nestled in Baker’s Park, quickly became the hub of the southern San Juans. Its name, "Silverton," was reportedly chosen by its founder, Levi Leiter, after a prospector exclaimed, "We’re not going to call this Gold Run; we’re going to call it Silverton, because there’s more silver here than gold!" It was a supply center, a place for miners to rest, resupply, and occasionally blow their hard-earned wages. Saloons, dance halls, and assay offices lined its dirt streets, and the clatter of hammers and the shouts of teamsters filled the air.

Just over the notorious Red Mountain Pass, a treacherous route even today, lay Ouray. Nicknamed the "Switzerland of America" for its stunning mountain backdrop, Ouray was a hotbed of silver and gold strikes. Its thermal hot springs, long known to the Utes, also provided a unique allure. Here, sophisticated mining operations like the Camp Bird Mine, founded by Thomas F. Walsh, extracted millions in gold. Walsh, a self-made man, would famously say of the Camp Bird, "It just goes down deeper than any other hole in the ground."

Further west, in a box canyon, grew Telluride, originally named Columbia. It became famous not only for its rich gold and silver mines but also for its pioneering use of alternating current (AC) electricity for industrial purposes. In 1891, the Ames Hydroelectric Generating Plant, just outside Telluride, became one of the first in the world to transmit AC power over a significant distance to run the compressors at the Gold King Mine. This technological leap dramatically increased efficiency and production, showcasing the innovative spirit of the mining era.

Other towns like Lake City, Ophir, Rico, and Gladstone also sprang up, each with its own story of boom and bust, each a testament to the relentless pursuit of mineral wealth.

The Lifeline: Railroads and Engineering Marvels

The scale of hard-rock mining demanded more than pack mules. It required heavy machinery, tons of supplies, and efficient transport for the ore. The solution came in the form of narrow-gauge railroads, engineering marvels that defied the seemingly impossible terrain.

The Denver & Rio Grande Railroad (D&RG), under the ambitious leadership of General William Jackson Palmer, began pushing its tracks into the mountains. In 1882, the D&RG reached Durango, and by 1882-83, the Silverton Railroad, a subsidiary, began laying tracks from Silverton up into the mining districts, eventually connecting to the main D&RG line. The construction was brutal: blasting through solid rock, carving ledges into sheer cliffs, and building trestles over dizzying gorges.

"The Iron Horse has truly conquered the impossible," declared the Silverton Miner newspaper upon the arrival of the first train. The railroads revolutionized the mining industry, drastically reducing freight costs and time. What once took weeks by mule train now took hours by rail. They brought in everything from massive stamp mills and giant steam engines to food, whiskey, and the mail, and carried out millions of dollars worth of ore. The sight and sound of a narrow-gauge locomotive chugging through the mountains, its whistle echoing off the canyon walls, became the very heartbeat of the mining economy.

Life in the Mines: Danger and Camaraderie

Life for the miners themselves was incredibly tough. Underground, the work was dark, damp, and dangerous. Explosions, cave-ins, and the insidious threat of silicosis (miner’s lung) were constant companions. A miner’s average lifespan was significantly shorter than those in other professions. Wages were decent for the time, but the cost of living in remote mountain towns was high, and many a miner’s pay packet ended up in the local saloon or gambling hall.

Despite the hardships, a strong sense of community often developed. Miners formed unions, pooled resources, and looked out for one another. They built churches, schools, and hospitals, trying to establish some semblance of normalcy in their isolated, transient lives. Women, often running boarding houses, laundries, or working as teachers and nurses, played a vital role in civilizing these raw frontier towns.

Boom and Bust: The Silver Panic of 1893

The mining economy of southwestern Colorado was largely built on silver. The U.S. government’s policy of bimetallism, which allowed silver to be minted into coins at a fixed ratio to gold, provided a stable market. However, this changed dramatically in 1893. The Silver Panic of 1893 was triggered by the repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which had required the government to buy large quantities of silver. With the government no longer obligated to purchase silver, its price plummeted.

The impact on the San Juans was immediate and devastating. Mines closed overnight, thousands lost their jobs, and entire towns emptied out. "The silver standard has brought us to our knees," lamented an editorial in the Ouray Herald. Many miners migrated to the remaining gold camps, like Cripple Creek, or left Colorado altogether. The bust underscored the inherent volatility of a single-commodity economy. While some mines managed to pivot to gold or other minerals, the region never fully recovered the widespread prosperity of the silver boom years.

The Lingering Legacy

Today, the San Juan Mountains remain dotted with the ghosts of this fervent past. Weather-beaten cabins cling to hillsides, rusting machinery lies half-buried, and mine portals stare like vacant eyes into the darkness. Ghost towns like Animas Forks and Eureka stand as poignant reminders of communities that once thrived. Yet, the legacy is not solely one of abandonment.

The towns of Silverton, Ouray, and Telluride, while no longer primarily mining towns, have reinvented themselves as vibrant tourist destinations, drawing on their rich history and unparalleled natural beauty. The Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad, originally built to haul ore, now carries thousands of tourists annually, offering a nostalgic journey through the very landscapes that once tested the mettle of pioneers.

The environmental impact of early mining is also a significant part of the legacy. Decades of unregulated mining left behind toxic tailings piles and acid mine drainage, which continue to affect water quality in the Animas River and its tributaries. Efforts to remediate these sites are ongoing, a complex and costly challenge that speaks to the long-term consequences of resource extraction.

The story of early southwestern Colorado mining is a powerful narrative of human endeavor against an awe-inspiring, yet formidable, natural world. It’s a tale of vast wealth and crushing poverty, of innovation and exploitation, of dreams realized and hopes dashed. The veins of gold and silver that once drew thousands to these mountains may largely be exhausted, but the indelible spirit of those who sought them – their grit, their ambition, and their enduring mark on the landscape – continues to resonate, a vital chapter in the unfolding story of the American West.