The Whispering Waters of Arrastre: California’s Forgotten Gold Rush Lifeline

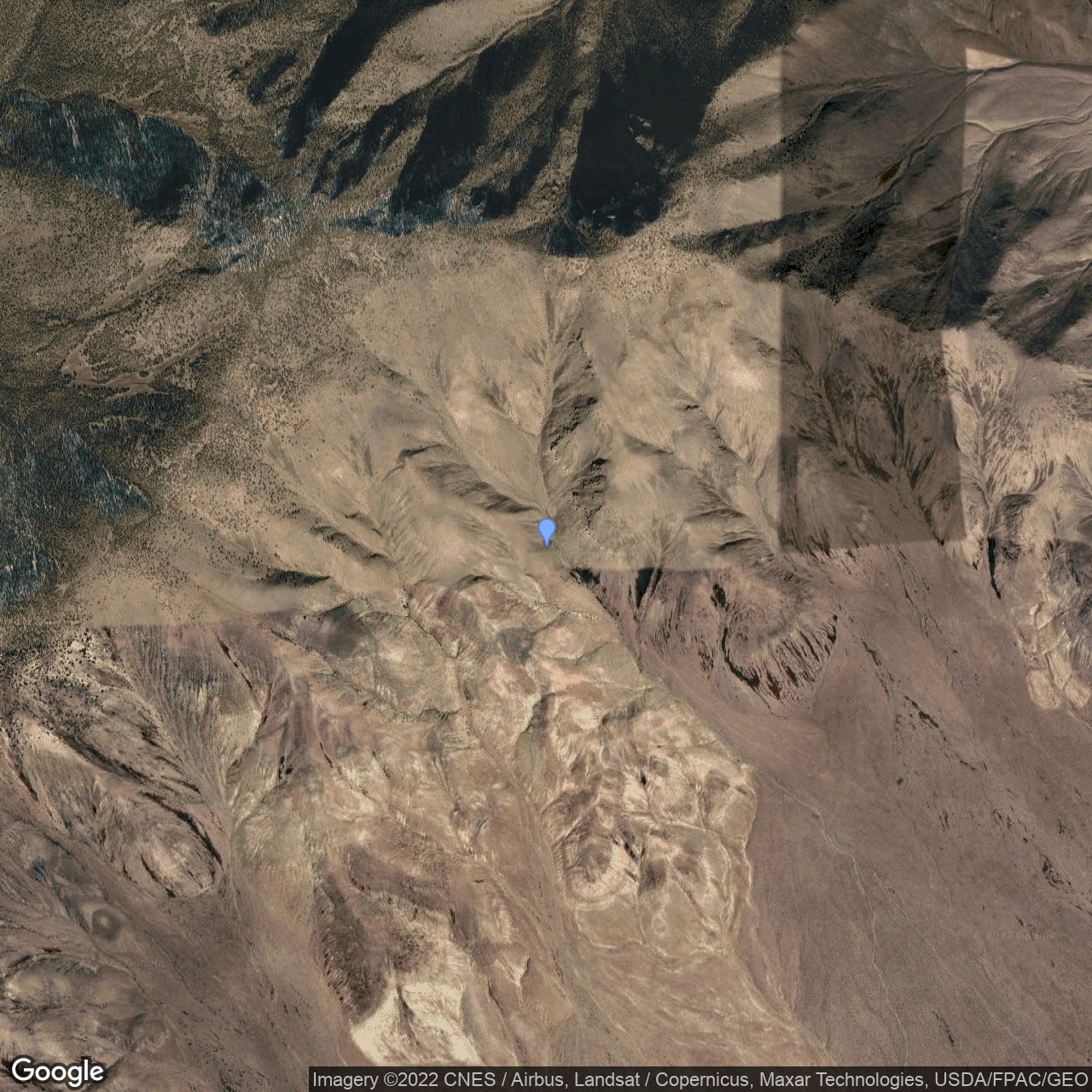

Deep within the rugged, sun-baked canyons and pine-scented forests of California’s Sierra Nevada, where the echoes of a frenetic past still seem to cling to the very air, lies a place whose name whispers tales of ingenuity, toil, and the relentless pursuit of gold: Arrastre Spring. More than just a geographical marker, this unassuming water source stands as a silent monument to a pivotal, yet often overlooked, chapter of the California Gold Rush – the transition from the easily panned placer gold to the stubborn, quartz-embedded riches that demanded a different kind of fight.

To understand the significance of Arrastre Spring, one must first understand the "arrastre" itself. This term, derived from the Spanish verb "arrastrar," meaning "to drag," refers to a primitive but remarkably effective milling device. Imagine a heavy stone, sometimes weighing several tons, tethered to a central post. A mule, horse, or even an ox would trudge in an endless circle, dragging this massive stone over a bed of quartz ore. The constant grinding, amplified by the addition of water, slowly but surely reduced the hard rock to a fine, gold-bearing powder, ready for amalgamation with mercury. It was a laborious, often brutal process, but for small-scale operations and prospectors lacking the capital for more sophisticated machinery, the arrastre was a lifeline.

And Arrastre Spring, wherever it was located across the vast expanse of California’s gold country, was the lifeblood of these operations. Without a reliable source of water, the arrastre would be nothing more than a static, useless monument to ambition.

From Placer to Quartz: The Gold Rush Evolves

The initial frenzy of the California Gold Rush, ignited by James W. Marshall’s discovery at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, was largely focused on placer mining. Gold, eroded from ancient veins, lay exposed in riverbeds and gravel bars, easily separated by pans, cradles, and sluice boxes. This was the era of the "forty-niner," the individual prospector with a pickaxe and a dream. But within a few years, the easily accessible surface gold began to diminish. The rivers had been turned over, the gravels sifted. Miners, driven by the insatiable desire for wealth, began to look deeper, into the solid rock formations – the quartz veins – where the gold originated.

This shift marked a profound change in the nature of the Gold Rush. Quartz mining was not a solitary endeavor; it required organized effort, capital, and technology. Shafts had to be sunk, tunnels blasted, and the hard, gold-bearing quartz extracted. Once brought to the surface, this ore had to be crushed to release the microscopic gold particles locked within its crystalline matrix. This is where the arrastre, and the springs that fed them, stepped into the spotlight.

The arrastre represented an intermediate technology. It was more advanced than a simple pan but far less sophisticated than the steam-powered stamp mills that would eventually dominate the landscape. Its appeal lay in its relative simplicity and low cost. A miner with a strong mule, some basic carpentry skills, and access to a constant water supply could set up an arrastre and begin processing his own ore, rather than relying on expensive commercial mills.

The Indispensable Flow: Why Water Was Gold’s Partner

For an arrastre to function, water was not merely helpful; it was absolutely critical. The water served several vital purposes:

- Lubrication and Grinding Medium: Water reduced friction between the grinding stone and the ore, making the process more efficient. It also helped carry away the pulverized rock, exposing fresh surfaces for grinding.

- Slurry Formation: As the ore was crushed, water mixed with the fine particles to create a slurry – a thick, muddy paste. This slurry was essential for the next step: amalgamation.

- Amalgamation: Mercury, introduced into the arrastre, would bind with the fine gold particles, forming an amalgam. The water helped keep the mercury in contact with the gold and allowed for easier separation of the amalgam from the waste rock.

- Drinking and Domestic Use: Beyond the mechanics of gold extraction, the spring provided potable water for the miners and their animals, sustaining life in often remote and arid environments.

Therefore, finding a quartz vein was only half the battle. Finding a quartz vein near a reliable spring was the true jackpot. Arrastre Spring, or any spring that bore that functional name, became a focal point of activity. Around such springs, temporary camps would spring up, sometimes growing into small, bustling communities. The rhythmic creak of the arrastre, the braying of mules, the shouts of men, and the constant murmur of the spring would have formed the soundtrack to daily life.

Life at the Spring: A Glimpse into the Past

Life for the arrastre miner was one of relentless toil. The work was physically demanding, often dangerous, and the rewards were far from guaranteed. They chipped away at rock faces, wrestled heavy stones into place, and endured the harsh elements. The dust, the noise, the mercury fumes – all contributed to a brutal existence. Yet, the promise of gold, that shimmering, elusive metal, kept them going.

Historical accounts from the era, though sometimes sparse regarding specific "Arrastre Springs," paint a vivid picture of the importance of water. One miner’s diary might note the anxiety caused by a dry spell, another the relief of a newly discovered spring. "The spring was not merely water," an imagined entry might read, "it was the very breath of our enterprise, without which the arrastre would stand silent, and our dreams would turn to dust."

These were often men on the fringes of society, driven by desperation or a thirst for adventure. They were immigrants from every corner of the globe – Chinese, Irish, Mexicans, Chileans, Germans – united by the common language of ambition and the shared hardship of the mining frontier. They cooked over open fires, slept in crude shelters, and often shared their meager provisions. The spring, therefore, wasn’t just an industrial asset; it was a social hub, a place where men gathered to drink, wash, and share stories, however briefly escaping the drudgery of their work.

The Fading Roar: Decline and Legacy

As the Gold Rush matured, technology advanced. The arrastre, efficient as it was for small operations, was slow and limited in its capacity. Larger, more powerful stamp mills, driven by steam engines or waterwheels, began to emerge. These mills could process hundreds of tons of ore per day, dwarfing the output of a mule-powered arrastre. With greater capital investment came deeper mines, more sophisticated extraction techniques, and eventually, the decline of the primitive arrastre.

As the richer quartz veins were exhausted, or as larger companies consolidated claims, many of the smaller arrastre operations became uneconomical. The miners moved on, following new strikes or abandoning the dream of gold altogether. The camps around the arrastre springs dwindled, then disappeared. The arrastres themselves fell into disrepair, their heavy stones settling into the earth, their wooden components rotting away. The springs, however, continued to flow, their waters whispering secrets to the wind, oblivious to the boom and bust cycles of human endeavor.

Today, the physical remnants of these arrastre operations are rare. A few preserved examples can be found in historical parks like Columbia State Historic Park or Bodie State Historic Park, offering a tangible link to this bygone era. But for many "Arrastre Springs," their exact locations might be lost to time, their names existing only on old maps or in dusty county records. They are often just faint depressions in the earth, a scatter of broken quartz, or perhaps the ghostly outline of a foundation stone, slowly being reclaimed by the wilderness.

The Enduring Significance

Yet, the story of Arrastre Spring, and the hundreds like it, remains profoundly significant. It is a microcosm of the entire California Gold Rush – a tale of human innovation in the face of daunting challenges, of relentless labor driven by hope, and of the transient nature of boomtown prosperity. It reminds us of the crucial role of natural resources, particularly water, in shaping human history and industry.

The springs were more than just sources of water; they were catalysts for industry, anchors for communities, and silent witnesses to the dreams and despair of countless individuals. They represent a fundamental truth: that even in the most ambitious and technologically advanced endeavors, the basic elements of nature remain indispensable.

Today, as hikers trek through the Sierra Nevada, they might stumble upon a forgotten spring, its waters still gurgling softly from the earth. They might not know its name, or the desperate human drama that once unfolded around it. But for those who understand the history, that spring is not just water; it is a living link to California’s foundational myth, a quiet testament to the enduring spirit of those who chased gold, and the essential role of a simple, flowing spring in making their dreams, however briefly, a reality. The whispering waters of Arrastre continue to tell a story, if only we take the time to listen.