The Whispers of a Nation: Unearthing America’s Enduring Legends, from Ancient Spirits to Modern Myths

America, a land forged in the crucible of migration, conflict, and innovation, pulses with a vibrant undercurrent of legend. These are not merely quaint folktales for children; they are the echoes of history, the embodiment of fears, hopes, and the very spirit of a diverse people. From the ancient, sacred narratives of its Indigenous inhabitants to the sprawling, often bizarre myths of the modern age, America’s legends offer a profound glimpse into its collective soul. Among the most potent and least understood of these are the intricate beliefs surrounding witchcraft within Native American traditions, particularly the Zuni people, where the concept of na’lashi (witches) weaves a complex tapestry of spiritual balance and societal fear.

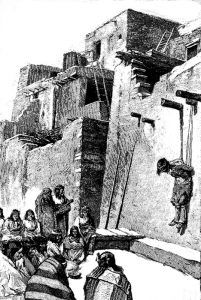

To truly understand America’s legendary landscape, one must first listen to the oldest voices—those of the Indigenous nations who walked this land for millennia. Their legends are not separate from their daily lives; they are the fabric of their existence, explaining the world, dictating social norms, and connecting them to the spiritual realm. Unlike the often whimsical or heroic legends of European origin, many Native American narratives delve into profound truths about creation, destruction, and the delicate balance of nature and humanity.

The Shadow and the Sacred: Zuni Witchcraft and the Na’lashi

Within the rich cultural tapestry of the Zuni people of New Mexico, a deeply spiritual and communal society, the concept of witchcraft, often referred to as na’lashi (witches) or those who practice na’lashi (the act of witchcraft), is a powerful and somber thread. It is not witchcraft as understood in Western pop culture, with broomsticks and spellbooks. Instead, Zuni witchcraft is rooted in the belief that certain individuals possess the ability to harness supernatural power for malevolent purposes, disrupting the harmony and balance that are paramount to Zuni life.

For the Zuni, the world is an interconnected web of spiritual forces, guided by benevolent deities and spirits known as Kachinas, who bring rain, fertility, and prosperity. But where there is light, there is also shadow. The na’lashi are individuals who, through envy, greed, or malice, turn away from the communal good. They are believed to transform into animals—coyotes, bears, owls—to inflict harm, steal souls, or cause illness, misfortune, or even death within the community. These are not external boogeymen; they are believed to be members of the community itself, often operating in secret, and their exposure or punishment traditionally served to restore balance and reaffirm communal values.

Anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons, in her extensive work on Zuni culture, documented the pervasive fear and belief in na’lashi during the early 20th century, noting how accusations and witch-hunts, while rare, could be devastating. The concept served as a powerful social control, discouraging envy, gossip, and any behavior that deviated from the cooperative, harmonious ideal. If a child fell ill inexplicably, if a harvest failed, or if an individual suffered a sudden string of misfortunes, the possibility of na’lashi activity would be considered. The fear was real, deeply embedded in the Zuni worldview, and was a testament to the immense power attributed to spiritual forces, both positive and negative, in shaping human destiny.

Crucially, understanding Zuni witchcraft requires moving beyond Western notions of "good" and "evil." It is about a disruption of hopi (balance and harmony) and the misuse of inherent power. The Zuni worldview emphasizes the collective over the individual, and the na’lashi represent the ultimate betrayal of that communal trust. While direct accusations and traditional punishments have largely faded due to modern legal systems and evolving societal norms, the stories and cautionary tales about na’lashi persist, serving as enduring reminders of the importance of community, humility, and the potential for malevolence lurking even within the familiar. They are a profound reflection of a people’s constant striving for spiritual and social equilibrium.

The Wild Frontier and the Birth of American Giants

As European settlers pushed westward, they brought their own folklore, blending it with the untamed landscape and the challenges of the New World. The dense forests of New England gave rise to tales of witches and spectral riders, most famously Washington Irving’s Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow, a phantom embodying the fears of the unknown lurking in the dark woods. These legends were often a fusion of Old World superstitions and New World anxieties, reflecting the struggle to tame a wild continent.

The 19th century, an era of rapid expansion and industrialization, saw the birth of distinctly American legendary figures: the larger-than-life heroes of the frontier. Paul Bunyan, the colossal lumberjack whose footsteps created lakes and whose blue ox, Babe, carved rivers, epitomized the American spirit of ingenuity and monumental effort required to conquer the wilderness. Johnny Appleseed, the gentle pioneer who spread apple seeds across the Midwest, symbolized the enduring hope and the benevolent spirit of those who sought to cultivate and settle the vast lands. These legends, often embellished by oral tradition and later by popular media, served to inspire and entertain, providing a narrative framework for the nation’s ambitious self-image.

Ghosts, Ghouls, and Glimmers of the Past

America’s bloody history, from colonial skirmishes to the Civil War, has bequeathed a rich legacy of ghost stories. Battlefields like Gettysburg are said to be rife with spectral soldiers, still fighting phantom battles. Old plantations in the South whisper tales of enslaved spirits, forever bound to the land where they suffered. Iconic locations like the Winchester Mystery House in California, with its baffling architecture, are believed to be built to appease restless spirits, reflecting a uniquely American blend of architectural eccentricity and supernatural belief.

These ghost stories are more than just spine-tingling entertainment. They are a way for a nation to grapple with its past, to acknowledge unresolved traumas, and to remember those who came before. They imbue historical sites with an emotional resonance, turning old buildings and landscapes into living monuments to the human experience.

Cryptids and the Modern Mythos

In the 20th and 21st centuries, as science and technology promised to demystify the world, new legends emerged—the cryptids. Bigfoot, the elusive ape-like creature said to roam the Pacific Northwest forests; the Mothman, a winged harbinger of doom in West Virginia; and the Chupacabra, a blood-sucking creature of Latin American folklore that has found a home in the American Southwest.

These modern legends speak to a persistent human need for wonder and mystery in an increasingly rationalized world. They tap into our primal fear of the unknown, our fascination with the wild fringes of nature, and sometimes, our distrust of official narratives. Bigfoot, for example, embodies the last vestiges of true wilderness, a symbol of nature’s unconquered spirit in an era of environmental degradation. The Mothman, often linked to the collapse of the Silver Bridge in 1967, represents the anxieties surrounding industrial accidents and the fragility of human constructs. These creatures thrive in the digital age, spreading rapidly through online forums and documentaries, evolving with each retelling but always retaining their core appeal: the tantalizing possibility that there is more to the world than meets the eye.

The Enduring Power of Story

America’s legends, from the deeply sacred na’lashi narratives of the Zuni to the towering tales of Paul Bunyan and the eerie encounters with cryptids, form an indelible part of its cultural identity. They are not static relics but living, breathing stories that evolve with each generation, adapting to new fears and hopes while retaining their fundamental lessons.

They teach us about the land itself—its vastness, its mysteries, its power. They reflect the aspirations of a people—to conquer, to build, to find meaning. They expose the fears that haunt us—of the unknown, of the malevolent, of our own past misdeeds. And perhaps most importantly, they remind us of the universal human need to tell stories, to make sense of a chaotic world, and to connect with something larger than ourselves. In the whispers of these legends, America truly finds its voice, a chorus of diverse narratives echoing through time, revealing the enduring magic and complexity of a nation still writing its own story.