The Whispers of the Wild: William Henry Vanderburgh and the Legends of America

America, a land of sprawling vistas and boundless ambition, has always been fertile ground for the birth of legends. From the mist-shrouded peaks of the Appalachians to the sun-baked deserts of the Southwest, from the deep, dark forests of the Pacific Northwest to the vast, untamed plains, every corner of this continent seems to hum with stories of the impossible, the heroic, and the utterly inexplicable. These are not merely fanciful tales; they are the cultural bedrock, the collective dreams and fears of a nation still defining itself, shaping its identity against a backdrop of wilderness and wonder. To truly understand these legends, one must consider the figures who lived on the cusp of the known and unknown, men like William Henry Vanderburgh, whose very existence in the raw American frontier placed him at the heart of where myths were born and whispered into being.

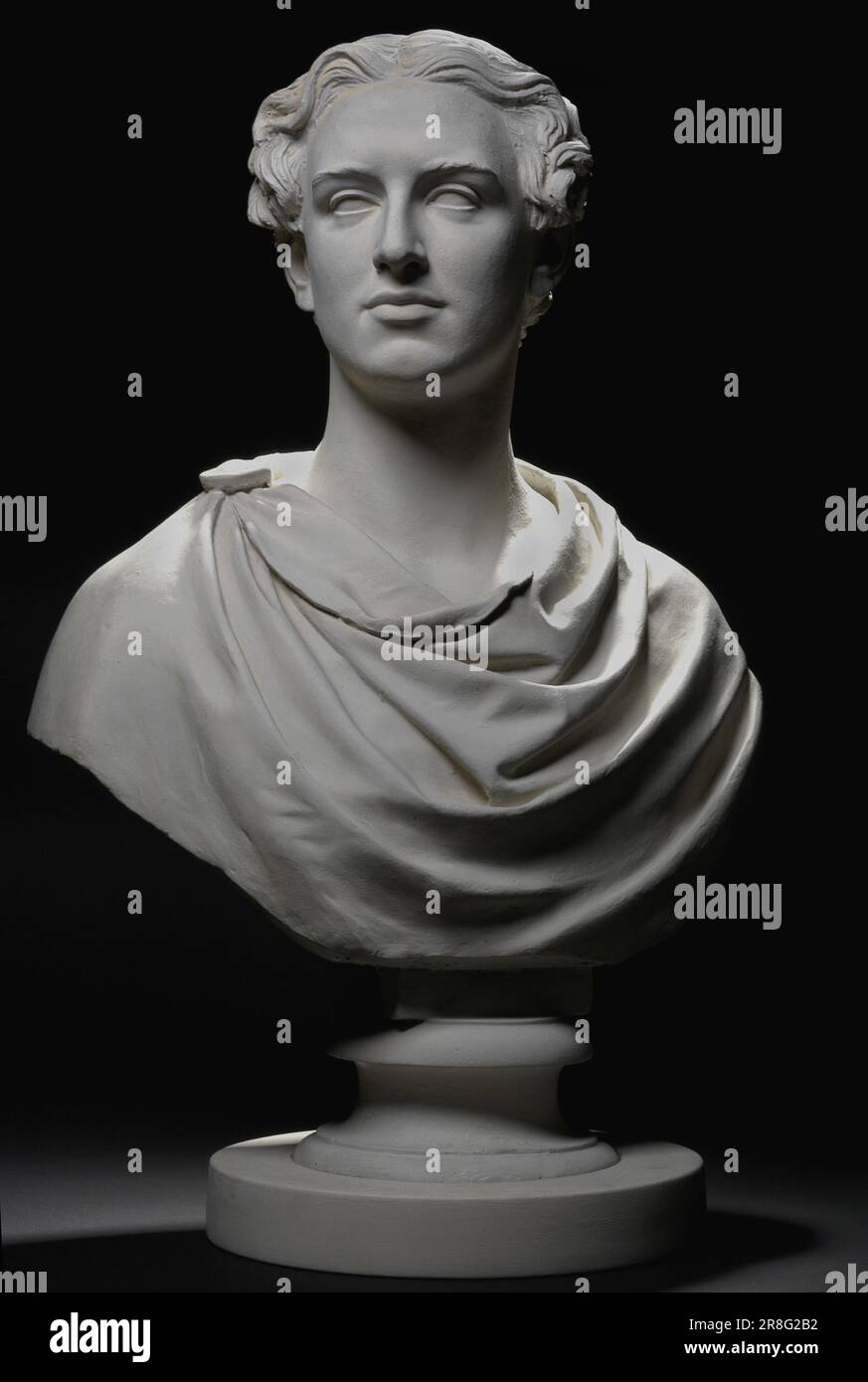

Vanderburgh, an officer in the U.S. Army and later a prominent figure in the fur trade, was a man forged in the crucible of the early 19th-century American West. His life, a relentless trek through uncharted territories, brought him face-to-face with the raw, untamed heart of the continent. He navigated treacherous rivers, scaled forbidding mountains, and negotiated with, or clashed against, the indigenous peoples who had called these lands home for millennia. It was an era when maps were largely blank canvases, and every distant sound, every fleeting shadow, held the potential for either discovery or dread. Vanderburgh’s world was one where the lines between fact and folklore blurred, a time when the very act of survival was often legendary.

The legends of America are as diverse as its landscapes. They speak of incredible feats of strength, uncanny wisdom, terrifying beasts, and spectral encounters. Many, like the iconic Paul Bunyan and his blue ox, Babe, are exaggerated tales born from the grueling labor of logging camps. Bunyan, a colossal lumberjack who carved out lakes with his axe and straightened rivers with a flick of his wrist, embodies the American spirit of conquering the wilderness, taming nature with sheer will and immense power. His stories, passed down by word of mouth, celebrated the hardworking individual and the communal effort required to shape a young nation.

Similarly, Johnny Appleseed (John Chapman), the benevolent pioneer who roamed the Midwest planting apple orchards, became a legend of generosity and foresight. His gentle nature and commitment to nurturing the land stood in stark contrast to the often-brutal realities of frontier expansion. He represented the hope of settled abundance in a wild land, a counterpoint to the more aggressive legends of conquest.

Then there’s Pecos Bill, the quintessential cowboy of the Southwest, who rode a mountain lion named Widow-Maker and lassoed a tornado. His tales reflect the audacious spirit of the cattle drives, the vastness of the plains, and the almost unbelievable challenges faced by those who sought to master the open range. These figures – Bunyan, Appleseed, Bill – are more than mere characters; they are allegories, personifications of the virtues and struggles that defined the nation’s formative years. Vanderburgh, traversing the same untamed landscapes, would have been acutely aware of the forces these legends represented: the immense power of nature, the necessity of hard work, and the boundless potential for human endeavor. He would have heard these types of stories, perhaps in nascent forms, around flickering campfires, told by weary trappers or hopeful settlers.

Beyond these celebrated folk heroes lie the creatures of American myth, the cryptids and monsters that haunt its wild places. The most famous among these is undoubtedly Bigfoot, or Sasquatch, a large, ape-like creature said to roam the dense forests of the Pacific Northwest. Stories of the "wild man of the woods" predate European settlement, deeply rooted in the oral traditions of indigenous tribes. For Vanderburgh, pushing into territories where no white man had trod, the possibility of encountering unknown species was a daily reality. His journals, though not extensively detailing such encounters, would likely have held accounts of strange tracks, unusual calls, or fleeting glimpses that, in less scientific times, would have been attributed to such mysterious beings. The very remoteness and primordial feel of the wilderness he explored made it a perfect incubator for such tales.

Further east, in the dark, foreboding Pine Barrens of New Jersey, lurks the Jersey Devil, a winged, horse-headed creature with bat-like wings, said to be the cursed 13th child of a local woman. In the mountains of West Virginia, the terrifying Mothman with its glowing red eyes has been sighted, often preceding disaster. These localized legends, while geographically specific, resonate with a universal human fear of the unknown and the uncanny. They speak to the anxieties of communities grappling with their environment, projecting their fears onto grotesque forms that embody the inexplicable.

Vanderburgh, a man of his era, would have possessed a blend of pragmatism and a healthy respect for the unseen. While his military and fur-trading mind was focused on logistics and survival, the world around him was steeped in superstition. Every unexplained event, every shadow, every strange sound in the deep wilderness could be interpreted through the lens of local lore. The frontier was not just a physical space; it was a psychological one, where the rational mind often wrestled with the primal fear of the unknown.

Perhaps the most profound connection between Vanderburgh’s world and American legends lies in the rich tapestry of Native American oral traditions. As an explorer and fur trader, he would have interacted extensively with numerous tribes, hearing their stories of creation, their spiritual beliefs, and their accounts of powerful beings that shaped their world. Figures like the Wendigo, a monstrous spirit from Algonququian folklore, embodying insatiable hunger and cannibalism, would have been part of the terrifying narratives of the northern forests. The Thunderbird, a massive bird spirit associated with storms and power, is a pervasive figure across many indigenous cultures, representing cosmic might.

These were not "legends" in the sense of tall tales for the indigenous peoples; they were deeply sacred narratives, spiritual truths that guided their understanding of the world. Vanderburgh’s encounters with these cultures would have opened a window into a belief system far older and more nuanced than his own. While he may have viewed some aspects through a Eurocentric lens, the sheer power and pervasive nature of these stories would have been undeniable. His own death in 1832, at the hands of Blackfeet warriors, underscores the perilous and often fatal interactions between cultures, interactions that themselves became the stuff of frontier legend and historical record. He died in a land where every tree, every river, every rock had a story, a spirit, a history.

American legends also include the spectral and the haunted. The Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow, a classic American ghost story rooted in Dutch folklore, captures the eerie beauty of the colonial landscape and the enduring power of supernatural terror. Later, more modern haunted locations like the Winchester Mystery House in California or the specters of Alcatraz prison demonstrate the nation’s ongoing fascination with restless spirits and tragic pasts. These tales, from the colonial period to the industrial age, reflect the evolving anxieties of American society – from fear of the unknown lurking in the woods to the weight of historical injustices and personal tragedies.

What unites these disparate legends – the mighty heroes, the elusive beasts, the ancient spirits, and the lingering ghosts – is their function. They serve as cultural touchstones, transmitting values, warning against dangers, explaining the inexplicable, and giving voice to collective hopes and fears. They are a means of making sense of a vast, often overwhelming continent, imbuing its mountains, rivers, and forests with meaning. They remind us of humanity’s place within nature, of the enduring power of good over evil, and of the thin veil between the mundane and the miraculous.

William Henry Vanderburgh, a man whose life was inextricably linked to the untamed American frontier, serves as a poignant, if silent, witness to this unfolding tapestry of myth. He was a man who lived and died in a landscape where legends were not merely stories but often felt like palpable realities. His tireless expeditions into the wilderness, his encounters with indigenous tribes, his very struggle for survival in a land that was both beautiful and brutal, mirrored the themes that underpin so many American legends. He did not create the myths of Paul Bunyan or Bigfoot, but he lived in the very conditions that gave them life. He walked the ground where they were whispered, where they were believed, where they took root in the American imagination.

In a modern world increasingly devoid of true mystery, the legends of America continue to captivate. They are a testament to the enduring human need for narrative, for meaning beyond the tangible. They are the echoes of a wilder time, a time when the continent was still largely unwritten, and every horizon held the promise of a new story. And in the shadowy figures of men like William Henry Vanderburgh, we glimpse the real-life courage and curiosity that dared to venture into that legendary unknown, forever intertwining their destinies with the very myths they helped to inspire. The whispers of the wild still carry their names, and the legends of America continue to tell their tales.