Thunder on the Rappahannock: The Crucible of Cavalry in the American Civil War

The Rappahannock River, a serpentine vein weaving through the heart of Virginia, was more than just a geographical feature during the American Civil War; it was a contested frontier, a strategic prize, and, critically, the proving ground for the mounted arm of both the Union and Confederate armies. From audacious raids to the largest cavalry battle ever fought on North American soil, the Rappahannock theatre witnessed the transformation of cavalry from a supporting role into a decisive force, forever altering the landscape of warfare.

For much of the war’s early stages, the very mention of cavalry conjured images of the dashing Confederate "Jeb" Stuart, his plumed hat and golden spurs emblematic of Southern martial prowess. His "eyes and ears" for Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were legendary, capable of audacious rides around Union forces, gathering intelligence, disrupting supply lines, and demoralizing the enemy. The Union cavalry, by contrast, was often derided as little more than mounted messengers, plagued by poor leadership, inadequate training, and an inferiority complex. They were frequently outmaneuvered, outfought, and outshone.

The strategic importance of the Rappahannock cannot be overstated. Flowing southeastward, it formed a natural barrier, often delineating the front lines between the two great armies. Control of its crossings – Kelly’s Ford, Beverly’s Ford, Rappahannock Station – was paramount, offering gateways into enemy territory for reconnaissance, raiding, or full-scale offensives. The flat, open plains of Culpeper County, adjacent to the river, provided ideal terrain for large-scale mounted operations, making it an inevitable stage for cavalry clashes.

The Rise of Union Cavalry: A Hard-Won Transformation

The turning point for the Union cavalry began not with a single brilliant charge, but with a painful period of reorganization and a newfound determination to match their Southern counterparts. Under commanders like Alfred Pleasanton, John Buford, and David Gregg, the Federal horsemen began to shed their amateurish image. They received better horses, more rigorous training in dismounted combat (recognizing the carbine as a primary weapon), and, crucially, a shift in mindset. They stopped reacting and started initiating.

This burgeoning confidence was put to its first major test in March 1863, at Kelly’s Ford. A Union force of approximately 2,100 cavalrymen under Brigadier General William W. Averell, supported by artillery, crossed the Rappahannock with the objective of disrupting Confederate communications and surprising Stuart’s cavalry. They met fierce resistance from Confederate Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee’s brigade, a veteran unit.

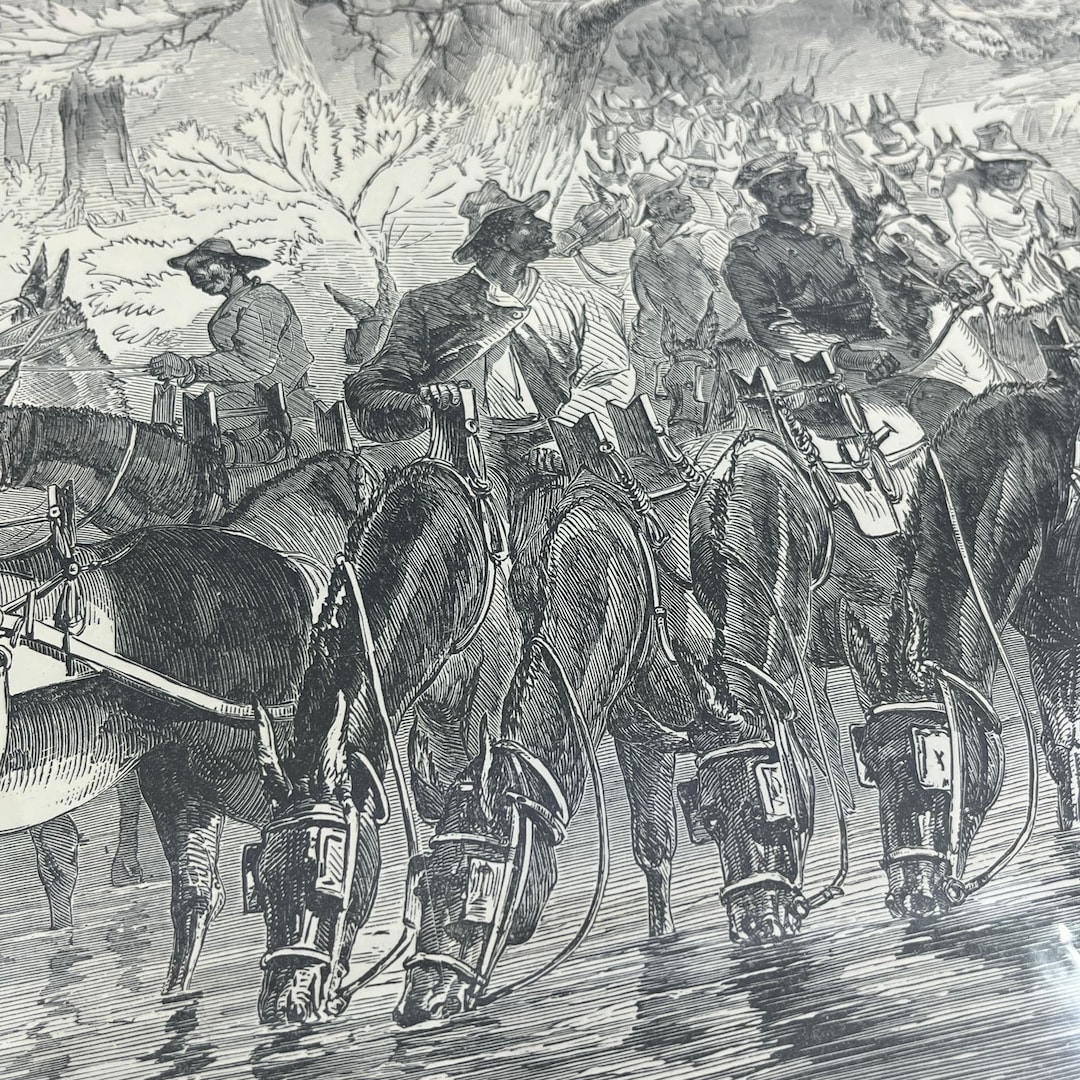

The fighting at Kelly’s Ford was a brutal, often hand-to-hand affair, characterized by repeated charges and dismounted skirmishes across open fields and through dense woods. The Union cavalry, for the first time, held its own, demonstrating a tenacity and tactical acumen previously unseen. They fought with a new ferocity, surprising the Confederates who had grown accustomed to easy victories. As historian Frank A. O’Reilly notes, "The fight at Kelly’s Ford was no mere skirmish; it was a declaration of intent. The Federals were no longer content to be ridden over."

Though the Union force eventually withdrew, having inflicted and sustained roughly equal casualties, the psychological victory was immense. The Confederates were shocked by the unexpected resistance, and the Union cavalry, though not achieving a decisive tactical victory, gained invaluable experience and, more importantly, a belief in their own capabilities. The battle also tragically claimed the life of Confederate Major John Pelham, the brilliant young artillery officer known as "Gallant Pelham," a severe blow to Stuart’s command.

Brandy Station: The Thunderous Dawn

Just three months after Kelly’s Ford, the Rappahannock theatre erupted in an unprecedented conflagration that would redefine cavalry warfare: The Battle of Brandy Station, fought on June 9, 1863. This colossal engagement, the largest cavalry battle in North American history, involved nearly 20,000 horsemen and served as the curtain-raiser for the Gettysburg Campaign.

General Robert E. Lee, preparing for his second invasion of the North, had concentrated his army around Culpeper, Virginia, just west of the Rappahannock. Stuart, eager to impress Lee and silence any lingering doubts after Kelly’s Ford, had staged a grand review of his cavalry corps near Brandy Station, a spectacle of flags, polished sabres, and thundering hooves. This display, however, inadvertently revealed his position to the Union high command.

Union Major General Alfred Pleasanton, commanding the newly formidable Federal Cavalry Corps, planned a surprise attack across the Rappahannock with two columns. Brigadier General John Buford’s division was to cross at Beverly’s Ford, while Brigadier General David Gregg’s column was to cross downstream at Kelly’s Ford and strike Stuart’s flank. The objective was to "disperse and harass the enemy’s cavalry" and determine Lee’s intentions.

The battle began at dawn as Buford’s troopers crashed into Confederate pickets at Beverly’s Ford, catching Stuart’s men completely by surprise. The fighting was immediate and savage, with dismounted carbine fire echoing across the fields, interspersed with desperate sabre charges. Buford’s men pushed the Confederates back towards Brandy Station and the strategic high ground of Fleetwood Hill, where Stuart’s headquarters had been.

Meanwhile, Gregg’s column, after a difficult crossing at Kelly’s Ford, arrived on the Confederate right flank, striking towards Fleetwood Hill. This simultaneous pressure from two directions created chaos and confusion within Stuart’s lines. Fleetwood Hill became the epicentre of the battle, changing hands multiple times in a desperate struggle. Charges and counter-charges, often in swirling dust and smoke, characterized the fighting. "The air was filled with the whiz of bullets, the clang of sabres, and the shouts of men," one Union trooper recalled.

By late afternoon, after more than ten hours of relentless fighting, Pleasanton, having achieved his objective of locating Lee’s army and proving his cavalry’s mettle, ordered a withdrawal back across the Rappahannock. The casualties were heavy on both sides, with the Confederates suffering slightly more.

Brandy Station was not a decisive victory for either side in terms of ground held, but its psychological and strategic impact was profound. For the Union cavalry, it was a triumph. They had not only held their own but had also initiated the attack, surprised Stuart, and fought him to a standstill on his own ground. The "Jeb Stuart myth" of invincibility was shattered. Stuart himself admitted to "dark days" following the battle, facing criticism for being caught unawares. For the first time, the Union cavalry had demonstrated its parity, if not superiority, with its Confederate counterpart, a crucial development that would play a vital role in the upcoming Gettysburg Campaign.

Beyond Brandy Station: The Continued Struggle

The Rappahannock remained a flashpoint for cavalry operations throughout 1863 and beyond. Following Brandy Station, Union cavalry continued to probe and fight through engagements like Aldie, Middleburg, and Upperville, as they shadowed Lee’s march north towards Pennsylvania. These skirmishes, though smaller, further honed the Union cavalry’s skills and cemented their aggressive posture.

In November 1863, during the Mine Run Campaign, cavalry played a critical role in screening infantry movements and engaging enemy forces at locations like Rappahannock Station and Mine Run. The Federal horsemen, now confident and well-led, effectively performed their roles of reconnaissance, screening, and flank protection, preventing the kind of surprises that had plagued earlier Union campaigns.

Tactics, Technology, and the Evolution of Warfare

The cavalry operations around the Rappahannock showcased the evolving tactics of the Civil War. While the romantic image of the sabre charge persisted, the reality was often far more brutal and reliant on firepower. Cavalry increasingly fought dismounted, using their carbines (like the Spencer or Sharps) and revolvers (Colt, Remington) as mounted infantry. This allowed them to hold defensive positions, pour accurate fire into enemy lines, and quickly remount to pursue or reposition. Horse artillery, with its speed and mobility, also became an indispensable component of cavalry commands, providing crucial fire support.

The Rappahannock operations underscored the fundamental importance of cavalry as the "eyes and ears" of the army. Their ability to gather intelligence, screen infantry movements, and raid enemy communications was vital. But they also demonstrated that cavalry could be more than just scouts; they could be a potent fighting force capable of engaging and defeating enemy cavalry, and even disrupting infantry formations.

Legacy of the Rappahannock Cavalry

The Rappahannock River was truly a crucible for cavalry during the American Civil War. It was here that the Union mounted arm shed its inferiority complex, learned to fight effectively, and ultimately matched, then arguably surpassed, its legendary Confederate counterpart. The battles of Kelly’s Ford and Brandy Station stand as monumental milestones in this transformation, marking the ascendancy of Federal cavalry and signaling a profound shift in the dynamics of the war.

The lessons learned on the plains and riverbanks of the Rappahannock – about leadership, training, tactics, and the sheer courage of the men and horses involved – resonated throughout the remainder of the conflict and beyond. The cavalry operations in this theatre did not just determine the fate of specific battles; they fundamentally reshaped the understanding of mounted warfare, leaving an indelible mark on military history. The thunder of hooves and the clash of sabres along the Rappahannock echo still, a testament to the epic struggle that unfolded there.