Timothy O’Sullivan: The Unflinching Eye of America’s Frontier

In the grand tapestry of American history, certain figures, though instrumental, often remain in the shadow of their more celebrated contemporaries. Timothy O’Sullivan, a name that might not immediately resonate with the general public, stands as one such essential, yet frequently overlooked, pioneer. His lens, a window into the raw, unvarnished truth of a nation in flux, captured the brutal aftermath of the Civil War and the breathtaking, untamed expanse of the American West with an unflinching realism that redefined the very purpose of photography. More than a mere technician, O’Sullivan was an artist whose stark, objective vision chronicled a pivotal era, shaping perceptions of war, wilderness, and the very identity of a burgeoning superpower.

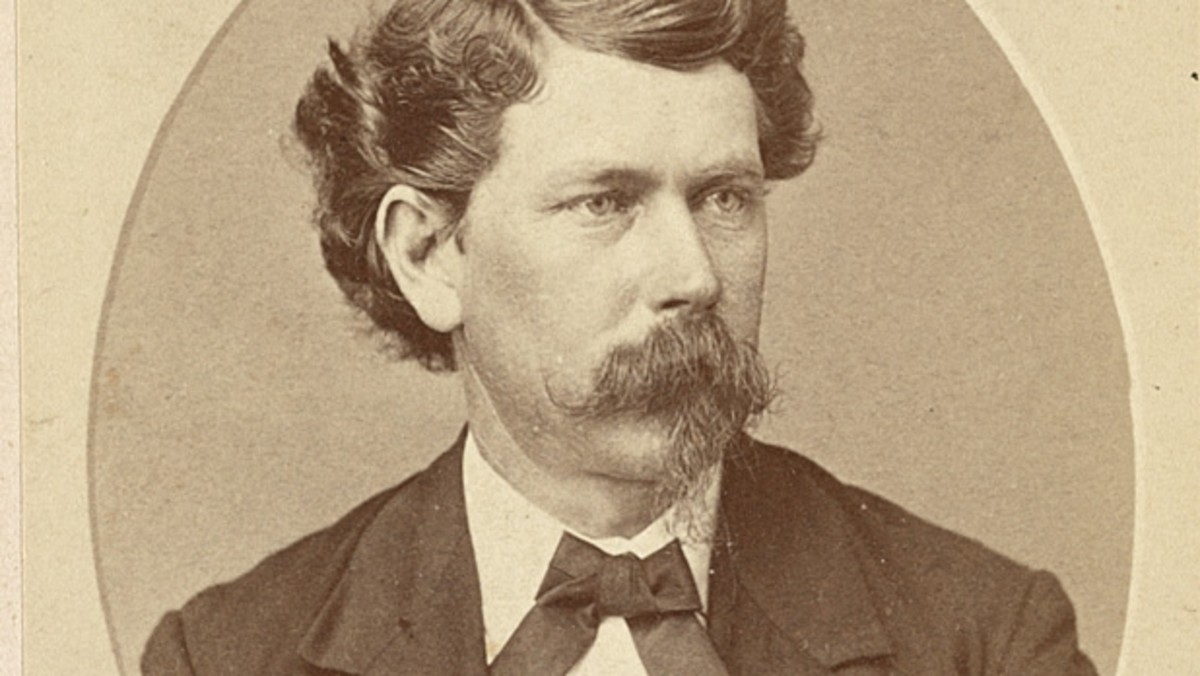

Born in Ireland around 1840, O’Sullivan’s journey to photographic renown began, like many of his era, in the bustling studios of New York City. He apprenticed under the legendary Mathew Brady, the visionary entrepreneur who famously declared, "The camera is the eye of history." It was within Brady’s tutelage, and later in Alexander Gardner’s studio after a professional split, that O’Sullivan honed his craft, mastering the laborious and demanding wet-plate collodion process. This intricate technique required photographers to prepare a glass plate with light-sensitive chemicals, expose it, and develop it on-site before the emulsion dried – a logistical nightmare even in a controlled studio, let alone on a battlefield or in the remote wilderness.

It was the American Civil War (1861-1865) that first thrust O’Sullivan into the crucible of history. While Brady and Gardner are often credited with the iconic images of the conflict, many of the most harrowing and historically significant photographs were, in fact, captured by their intrepid staff photographers, O’Sullivan prominent among them. His work at sites like Gettysburg, Petersburg, and the immediate aftermath of battles, particularly at Antietam, offered a stark, unromanticized glimpse into the realities of modern warfare.

His photograph, "A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, July 1863," taken for Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, is perhaps his most enduring Civil War image. It depicts the bodies of fallen soldiers, bloated and distorted, strewn across a desolate field, stripped of their dignity and their boots. There is no heroism, no glory, only the grim, undeniable evidence of mass slaughter. O’Sullivan’s lens didn’t shy away from the gruesome details; instead, it presented them with a chilling detachment that forced viewers to confront the true cost of conflict. Unlike some of his contemporaries who might have posed bodies for dramatic effect, O’Sullivan’s approach was often one of stark, almost clinical, documentation. He showed war for what it was: a brutal, dehumanizing affair.

As the smoke of the Civil War cleared, the nation’s gaze shifted westward. The concept of Manifest Destiny, coupled with the burgeoning fields of geology, cartography, and resource extraction, spurred a series of ambitious government-sponsored surveys aimed at mapping, understanding, and ultimately settling the vast, unexplored territories. This new frontier became O’Sullivan’s next, and perhaps most significant, canvas.

Between 1867 and 1874, O’Sullivan embarked on a series of expeditions that would cement his legacy. His first major post-war assignment was with Clarence King’s Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel. King, a brilliant and ambitious geologist, understood the power of photography not just as a visual record but as scientific evidence. For five years, O’Sullivan traversed parts of Nevada, Utah, and California, enduring unimaginable hardships. His portable darkroom, a cumbersome tent or wagon laden with glass plates, chemicals, and water, had to be hauled by mules, packed on his back, or even floated on makeshift rafts across rivers.

The images from the King Survey are characterized by their immense scale and geological focus. O’Sullivan was tasked with documenting rock formations, canyons, and vast, desolate landscapes that had never before been seen by the eyes of the eastern public. His photographs of the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada were not merely picturesque; they were vital scientific data. "Shoshone Falls, Snake River, Idaho" (1868) and "Ancient Ruins in the Cañon de Chelle, Arizona" (1873), though taken on later surveys, exemplify his ability to capture both the grandeur of nature and the subtle evidence of human history within it. He often dwarfed human figures within his landscapes, emphasizing the insignificance of man against the monumental power of nature and geological time. This stylistic choice became a hallmark of his Western work.

In 1870, O’Sullivan briefly diverted from the arid West to join the Darien Expedition, a U.S. Navy survey tasked with finding a suitable route for a trans-isthmian canal through Panama. This was a stark contrast to his previous work: dense, humid jungle, disease-ridden environments, and torrential downpours replaced the dry, expansive deserts. While less iconic than his Western work, the Darien photographs showcased O’Sullivan’s remarkable adaptability and resilience, proving his ability to document under the most extreme conditions imaginable.

Upon his return, O’Sullivan rejoined the Western surveys, this time with Lieutenant George M. Wheeler’s U.S. Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian (1871-1874). Wheeler’s survey was more explicitly military in its objectives, aiming to map and claim territories for the United States, often clashing with King’s more purely scientific endeavors. Despite the political rivalries, O’Sullivan continued his meticulous work, producing some of his most iconic and widely recognized photographs.

His images from the Wheeler Survey, particularly those of the Grand Canyon and the Black Cañon of the Colorado River, offered the American public their first comprehensive visual understanding of these natural wonders. The sheer scale and stark beauty of these landscapes, captured with O’Sullivan’s characteristic clarity, were awe-inspiring. His photograph "Black Cañon of the Colorado River, looking above from Camp 8" (1871) is a masterclass in composition, with the tiny survey boat appearing as a fragile speck against the towering, ancient walls of the canyon, once again emphasizing nature’s immense power.

The technical challenges O’Sullivan faced were monumental. The wet-plate collodion process demanded speed and precision. Glass plates had to be cleaned, coated with collodion, sensitized in a silver nitrate bath, exposed while still wet, and then developed immediately. In the scorching heat of the desert, the collodion could dry prematurely, ruining the plate. In the cold, chemicals could freeze. Water, essential for both the process and survival, was often scarce. Yet, O’Sullivan persevered, producing hundreds of pristine, large-format negatives that stand as testament to his skill and tenacity. Clarence King himself lauded O’Sullivan’s "indomitable energy and patience" in his official reports.

O’Sullivan’s photographic aesthetic was distinct. He was less interested in the dramatic romanticism often favored by other landscape artists of the time. His compositions were often stark, almost minimalist, focusing on geological forms, light, and shadow. Human presence, when depicted, was usually small, serving to emphasize the vastness of the environment rather than to imbue it with narrative drama. This objective, almost scientific, approach gave his photographs a powerful sense of authenticity. They were not just pretty pictures; they were records, visual truths.

His work fundamentally altered how Americans perceived their expanding nation. Before O’Sullivan, the West was largely a matter of rumor, fanciful paintings, and written accounts. His photographs brought its rugged reality into parlors and government offices across the country. They revealed a land of immense beauty, but also one of harshness, desolation, and ancient mysteries. They helped fuel the drive for settlement and resource exploitation, while simultaneously inspiring a sense of awe and wonder.

Despite his prolific output and the profound impact of his work, Timothy O’Sullivan never achieved widespread fame or financial security. After the surveys, he worked briefly for the U.S. Geological Survey and then for a mining company, his life fading into relative obscurity. He died in 1882, likely from tuberculosis, at the young age of 42.

Today, however, Timothy O’Sullivan is recognized as a pivotal figure in the history of photography. His Civil War images remain indispensable historical documents, while his Western landscapes are celebrated as masterpieces of early documentary photography. He was a pioneer who pushed the boundaries of his medium, both technically and artistically, proving that photography could be a powerful tool for scientific inquiry, historical record, and profound aesthetic expression. His legacy is etched not only in the annals of photography but in the visual memory of the American continent itself. Through his unflinching eye, we continue to see the raw, vital forces that shaped a nation.