Echoes in Cedar: The Enduring Grandeur of Tlingit Clan House Architecture

By [Your Name/Journalist Alias]

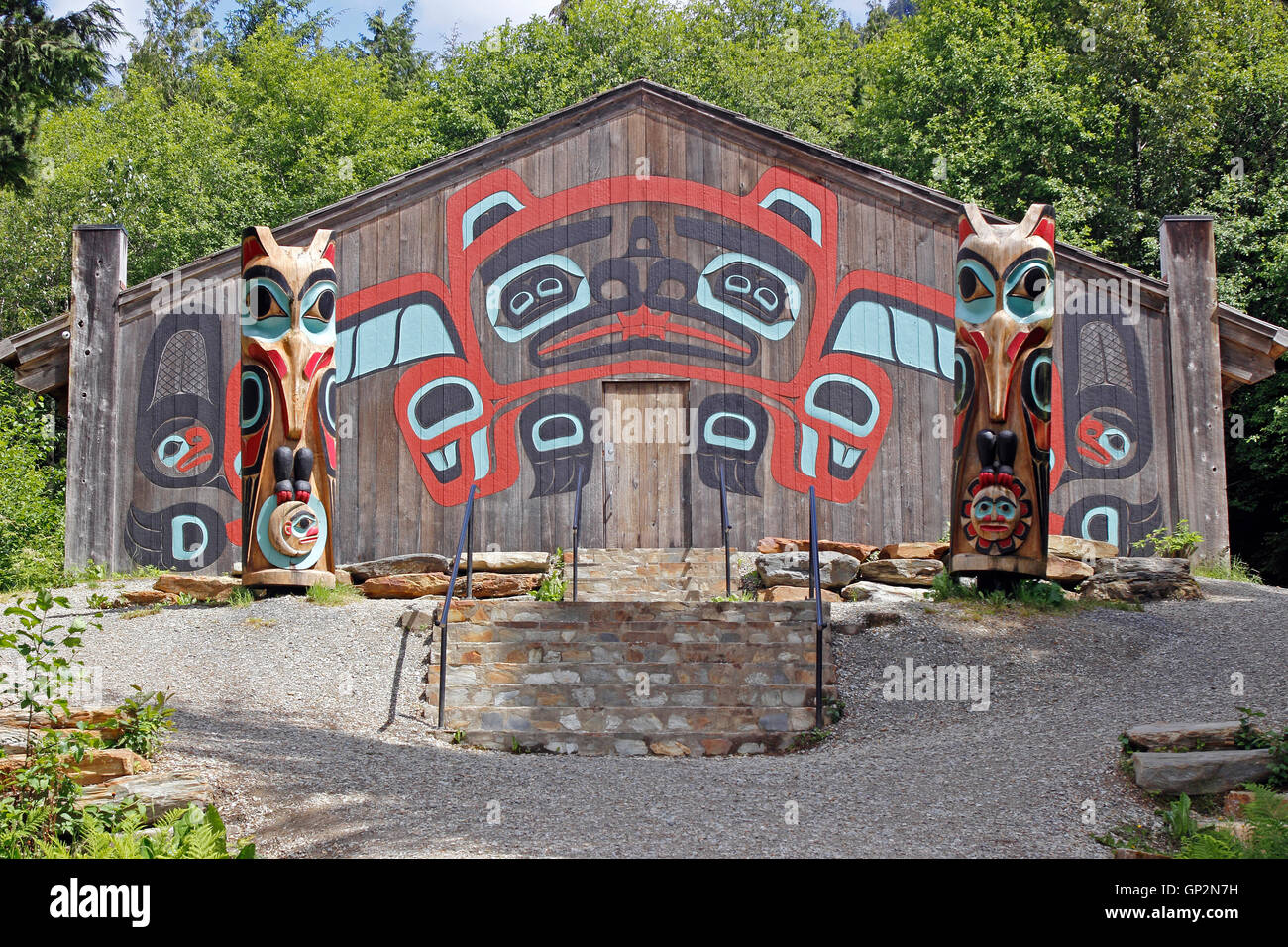

In the misty fjords and towering cedar forests of Southeast Alaska, where the Pacific Ocean meets ancient lands, stands a testament to ingenuity, artistry, and profound cultural connection: the Tlingit clan house. Far more than mere shelter, these colossal structures of wood were living entities, repositories of history, and the vibrant heart of a complex society. To step into an ancestral Tlingit clan house, or to behold its modern resurgence, is to witness an architectural tradition deeply intertwined with identity, spirituality, and the very fabric of the Tlingit universe.

For centuries, the Tlingit, one of the indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast, perfected a distinctive architectural style that harnessed the abundant natural resources of their environment, primarily the towering red cedar. These weren’t just buildings; they were a physical manifestation of Tlingit society’s matrilineal clan system, their spiritual beliefs, and their unparalleled woodworking prowess.

The Ancestral Blueprint: Engineering in Cedar

The typical Tlingit clan house, or Naa (meaning "house" or "living thing"), was a rectangular, gabled-roof structure of immense scale. Often measuring 40 to 60 feet wide and 60 to 100 feet long, with some even larger, these houses could accommodate multiple families within a single clan lineage. Their construction was a monumental undertaking, requiring collective effort, sophisticated engineering, and a deep understanding of the properties of wood.

The primary material was, without question, the Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata). Revered as the "Tree of Life" by Northwest Coast peoples, cedar was chosen for its remarkable qualities: its straight grain made it ideal for splitting into planks, its natural oils rendered it resistant to rot and insects, and its sheer size allowed for massive structural components.

"The Tlingit master builders understood cedar in a way modern engineers are only beginning to appreciate," notes Dr. Amy Mather, an anthropologist specializing in Indigenous architecture. "They didn’t just cut down trees; they engaged with them, respecting their spirit and utilizing every part for a specific purpose."

The construction began with the felling of enormous trees, often using stone adzes and wedges, a process that could take weeks. These massive logs were then painstakingly hauled to the building site, often over significant distances. The structural backbone of the Naa consisted of massive, upright cedar posts – sometimes 2 to 3 feet in diameter – sunk deep into the earth. These posts supported equally massive horizontal beams, forming a rigid, interlocking frame.

A remarkable feature of Tlingit architecture was the absence of nails or screws. Instead, builders employed ingenious joinery techniques: mortise and tenon joints, notched connections, and wooden pegs secured the heavy timbers together with incredible strength and precision. The walls were formed by splitting cedar logs into wide, thick planks, which were then fitted horizontally or vertically into grooves in the main structural posts. The gabled roof, designed to shed the region’s heavy rainfall, was also constructed of overlapping cedar planks. Smoke holes were strategically placed in the roof apex to allow smoke from the central hearth to escape.

Inside the Heartbeat of the Clan

Stepping inside a clan house was to enter a world of ordered communal living. The interior was typically organized around a large, central fire pit, the hearth that provided warmth, light, and served as the focal point for cooking and social gatherings. Above the hearth, a raised smoke hole allowed smoke to escape, though a persistent, pleasant aroma of woodsmoke always permeated the air.

Around the perimeter of the house, raised sleeping platforms, often two or three tiers high, provided individual family spaces. These platforms were sometimes partitioned by carved or painted screens, offering a degree of privacy within the communal dwelling. Storage areas for food, tools, and ceremonial regalia were often built beneath the platforms or in alcoves. The floor was typically packed earth, occasionally covered with woven mats.

The interior was not merely functional; it was also a canvas for artistic expression. Massive house posts, supporting the roof beams, were often intricately carved with clan crests – images of animals, mythical beings, or ancestors that represented the lineage’s history, rights, and privileges. These carvings were not just decorative; they were visual narratives, mnemonic devices for oral traditions, and powerful symbols of identity.

Beyond Shelter: A Canvas of Identity and Narrative

Perhaps the most iconic features associated with Tlingit clan houses are the towering totem poles that often stood before them. These monumental carvings, reaching heights of 50 feet or more, were not simply "idols" as early European observers often misconstrued. Instead, they were powerful statements of clan identity, historical records, and spiritual guardians. Each figure carved onto a pole represented a crest, a story, or an ancestral event belonging to the house’s inhabitants. They served as public declarations of a clan’s prestige, wealth, and the stories that defined them.

"The totem poles are like our libraries," explains a contemporary Tlingit elder, Daanaq’w (meaning "Strong Bear"). "They hold our history, our agreements, our humor, and our connection to the land and the spirit world. The house and the pole are inseparable; one tells the story of the other."

The house fronts themselves were often elaborately painted with bold, stylized designs incorporating clan crests and spirit beings, using natural pigments derived from minerals and plants. These painted facades, combined with the carved house poles and totem poles, transformed the clan house into a living monument, a visual embodiment of the clan’s spiritual and social power. The house was not merely a structure; it was a character in the clan’s ongoing narrative, often bearing a personal name like "House of the Raven," "House that Holds the Sky," or "Cloud House."

The Social and Ceremonial Hub: Potlatches and Lineage

The clan house was the undisputed center of Tlingit social and ceremonial life. It was here that daily activities unfolded: preparing food, weaving baskets, carving, and storytelling. But its most significant role was as the venue for potlatches – elaborate ceremonial feasts and gift-giving ceremonies that were central to Northwest Coast cultures.

Potlatches, hosted by a clan chief or head of a house, served multiple crucial functions: they validated claims to titles and resources, commemorated significant events like the raising of a new house or a death, redistributed wealth, and publicly displayed the host’s generosity and status. The sheer scale of these events, often involving hundreds of guests from other clans and villages, underscored the necessity of the large clan house as a communal gathering space. The house became a stage where power was asserted, alliances were forged, and cultural traditions were meticulously performed and passed down through generations.

Challenges, Resilience, and Revival

The arrival of European colonizers in the 18th and 19th centuries brought profound and often devastating changes to Tlingit society, including their architectural traditions. Disease, forced assimilation policies, the suppression of the potlatch (outlawed in Canada and effectively discouraged in the U.S.), and the introduction of new building materials and styles led to a decline in traditional clan house construction. Many ancestral houses were abandoned, fell into disrepair, or were dismantled. The knowledge of their intricate construction techniques, passed down orally for generations, began to erode.

However, the spirit of the Naa never truly died. In recent decades, a powerful movement of cultural revitalization has swept through Tlingit communities. This includes a renewed focus on traditional art forms, language, and, significantly, the reconstruction and creation of new clan houses.

Organizations like Sealaska Heritage Institute (SHI) in Juneau, Alaska, have been at the forefront of these efforts. SHI’s campus features a stunning clan house, Shuká Hít (Ancestors’ House), built using traditional techniques and materials, serving as a powerful educational and cultural center. This resurgence is not about simply replicating the past; it’s about re-engaging with traditional knowledge, adapting it for contemporary use, and ensuring its continuity.

"Building a new clan house today is more than just construction; it’s an act of sovereignty," says a contemporary Tlingit architect involved in one such project. "It’s about healing, about reclaiming our space, and about showing our youth that our culture is vibrant, alive, and strong." These modern houses often blend traditional aesthetics and construction principles with contemporary building codes and amenities, creating spaces that are both historically authentic and functionally relevant for the 21st century.

An Enduring Legacy

The Tlingit clan house, from its massive cedar timbers to its intricate carvings and painted facades, stands as a powerful symbol of a people deeply connected to their land, their history, and their identity. It embodies a holistic worldview where architecture, art, spirituality, and social structure are inextricably linked.

As these magnificent structures continue to rise again across Southeast Alaska, they are not merely monuments to a bygone era. They are living testaments to Tlingit resilience, a physical manifestation of cultural pride, and a powerful beacon for future generations, echoing the stories and strength of their ancestors in every grain of cedar. The Naa remains, as it always has been, a vibrant heartbeat of the Tlingit nation.