Guardians of Lineage: The Enduring Power of Tlingit Clan Systems and Crests

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

In the emerald embrace of Southeast Alaska, where ancient rainforests meet the glacial fjords of the Pacific, lives a people whose identity is woven into the very fabric of their landscape and history: the Tlingit. More than just a name for a distinct Indigenous nation, "Tlingit" translates to "People of the Tides," a testament to their profound connection with the sea. But beneath the surface of their everyday lives, a complex and enduring social structure—the Tlingit clan system, powerfully expressed through their crests—serves as the bedrock of their culture, governance, and spiritual beliefs.

Far from being mere decorative symbols, Tlingit crests are living narratives, embodying centuries of history, triumphs, migrations, and sacred encounters. They are the visual language of a society built on intricate relationships, responsibilities, and an unwavering respect for lineage. To understand the Tlingit, one must first grasp the profound significance of these emblematic markers.

The Duality of Identity: Raven and Eagle

At the heart of the Tlingit social order lies a dualistic structure, a system of two complementary halves known as moieties: the Raven (Yéil) and the Eagle (Ch’aak’). Every Tlingit individual is born into one of these two moieties, which is inherited matrilineally—meaning through the mother’s line. This is a fundamental principle: if your mother is Raven, you are Raven; if she is Eagle, you are Eagle.

This duality is not about opposition but about balance and reciprocity. Marriage within the same moiety is strictly forbidden; a Raven must marry an Eagle, and an Eagle must marry a Raven. This ensures the constant intertwining of the two halves, fostering interdependence and reinforcing social cohesion. In traditional Tlingit society, this system regulated not only marriage but also ceremonial roles, economic partnerships, and even the conduct of funerals, where the opposite moiety would perform crucial duties, ensuring proper respect and balance.

Within each moiety are numerous clans, each with its own unique history, traditional territories, and, most importantly, a distinct set of crests. For instance, within the Raven moiety, one might find clans like the Kiks.ádi (Frog/Killer Whale), L’uknax.ádi (Coho Salmon), or Deisheetaan (Beaver). On the Eagle side, prominent clans include the Wooshkeetaan (Shark/Wolf), Kaagwaantaan (Wolf/Bear), and Chookaneidí (Brown Bear). Each clan is further subdivided into "houses" (hít), which are specific extended family units, often named after their ancestral dwelling or location.

Crests: More Than Just Symbols

The crests associated with these clans are not arbitrary designs. They are powerful emblems, typically depicting animals, mythological beings, or natural phenomena, that serve as visual representations of a clan’s identity, history, and inherited rights. A crest might symbolize a clan’s origin story, a significant historical event, a migration, a spiritual encounter with an animal, or a claim to a particular territory or resource.

"Our crests are our identity, our history, our very being," explains Rosita Worl, a prominent Tlingit anthropologist and president of the Sealaska Heritage Institute. "They are not something you choose; they are something you inherit, something that carries the weight of your ancestors’ experiences and accomplishments."

Unlike a coat of arms in European heraldry, Tlingit crests are not merely decorative. They are deeply spiritual and legally significant. Each crest is considered the exclusive "property" of a specific clan or house, and its use is strictly controlled. One cannot simply appropriate a crest; it must be inherited, earned, or validated through specific events, most notably the potlatch.

Common crest figures include the Raven, Eagle, Bear, Wolf, Killer Whale, Beaver, Frog, Salmon, and Shark, among others. Each animal holds specific symbolic meanings within the Tlingit worldview, often reflecting qualities like strength, wisdom, cunning, or adaptability. For example, the Killer Whale (Keet) might represent power and prestige, while the Beaver (S’eek) could signify industriousness and resourcefulness.

The Potlatch: A Living Tapestry of Identity

The potlatch, a grand ceremonial feast and gathering, is the vital mechanism through which the Tlingit clan system and crests are publicly affirmed and perpetuated. For centuries, these elaborate events served as the cornerstone of Tlingit society, acting as a combined court, parliament, and cultural festival.

During a potlatch, a host clan would invite members of the opposite moiety to witness and validate significant life events: the raising of a totem pole, the naming of a chief, the transfer of property or titles, or the mourning of a deceased loved one. The host would display their inherited crests—on totem poles, button blankets, masks, carved boxes, and other ceremonial regalia—to publicly assert their lineage and rights. The generosity of the host, demonstrated by the distribution of vast amounts of gifts to the guests, was a crucial element. The more lavish the gifts, the greater the prestige and validation for the host clan.

This system of reciprocal giving and witnessing ensured that the oral histories, names, and crest rights associated with each clan were formally recognized and remembered by the entire community. It was a powerful act of governance, cultural transmission, and economic redistribution.

However, the potlatch, along with other Indigenous cultural practices, faced severe suppression during the colonial era. In 1884, the Canadian government (followed by similar bans in the U.S.) outlawed the potlatch, viewing it as an impediment to assimilation and Christianization. This ban, which lasted until 1951, forced many ceremonies underground, threatening the very fabric of Tlingit society. Despite the persecution, many Tlingit leaders and families risked imprisonment to continue their traditions, ensuring that the knowledge of their clan systems and crests survived.

Artistic Expression: Where Spirit Meets Form

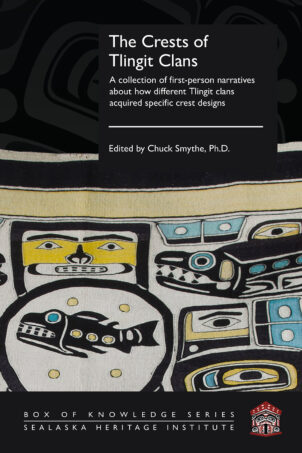

The visual artistry of the Tlingit is inextricably linked to their clan system and crests. From monumental totem poles that stand sentinel over coastal villages to intricately carved masks, elaborately beaded button blankets, and finely woven Chilkat robes, every piece of Tlingit art is a testament to the power of these ancestral symbols.

Totem Poles: Perhaps the most iconic expression, totem poles are not idols but mnemonic devices and genealogical records. Each carved figure on a pole represents a crest, telling a story or commemorating an event related to the clan that owns it. They stand as powerful assertions of lineage and history.

Button Blankets: These magnificent cloaks, typically made of wool or felt with mother-of-pearl buttons, are ceremonial regalia. The central design on a button blanket is always a clan crest, making the wearer a living embodiment of their ancestral identity during potlatches and other significant events.

Masks: Carved from wood, often with intricate inlays of abalone or copper, masks depict clan crests, spirit beings, or ancestors. Worn during ceremonial dances, they transform the wearer, allowing them to embody the spirit or character represented by the mask, further bringing the crests to life.

Bentwood Boxes and Chilkat Robes: Even utilitarian items like bentwood boxes, used for storage, or the exquisitely woven Chilkat robes, adorned with clan crests, transform into sacred objects, reflecting the Tlingit belief that art and spirituality are interwoven into daily life.

The distinctive "Formline" art style, characterized by its flowing, curvilinear shapes, ovoids, and U-forms, is the visual grammar through which these crests are depicted. It is a highly formalized system, yet capable of immense expressiveness, ensuring that the integrity and recognition of each crest are maintained across generations.

Resilience and Revival in the Modern Era

Today, the Tlingit clan system and the power of their crests continue to thrive. After the lifting of the potlatch ban, Tlingit communities embarked on a remarkable journey of cultural revitalization. Elders who had preserved the knowledge in secret began to teach the younger generations, language programs were established, and traditional art forms experienced a resurgence.

Modern potlatches are held, often adapted to contemporary life, but still serving their essential function of public validation and cultural transmission. Tlingit artists, many of whom are master carvers, weavers, and painters, continue to create breathtaking works, ensuring that the visual language of the crests remains vibrant and relevant.

The Tlingit clan system is not a relic of the past but a living, breathing framework that continues to define identity, guide social interaction, and inform political engagement. It is a testament to the resilience of a people who have faced immense challenges but have held fast to the intricate tapestry of their heritage.

In a world increasingly grappling with questions of identity and belonging, the Tlingit clan system and its crests offer a profound model of how a society can maintain deep historical connections, govern itself through complex relationships, and find strength in the enduring power of its ancestral narratives. The Tlingit, the People of the Tides, continue to navigate the currents of change, their crests shining brightly as beacons of their unwavering spirit and timeless identity.