Sentinels of Cedar: The Enduring Legacy of Tlingit Haida Totem Pole Carving Traditions

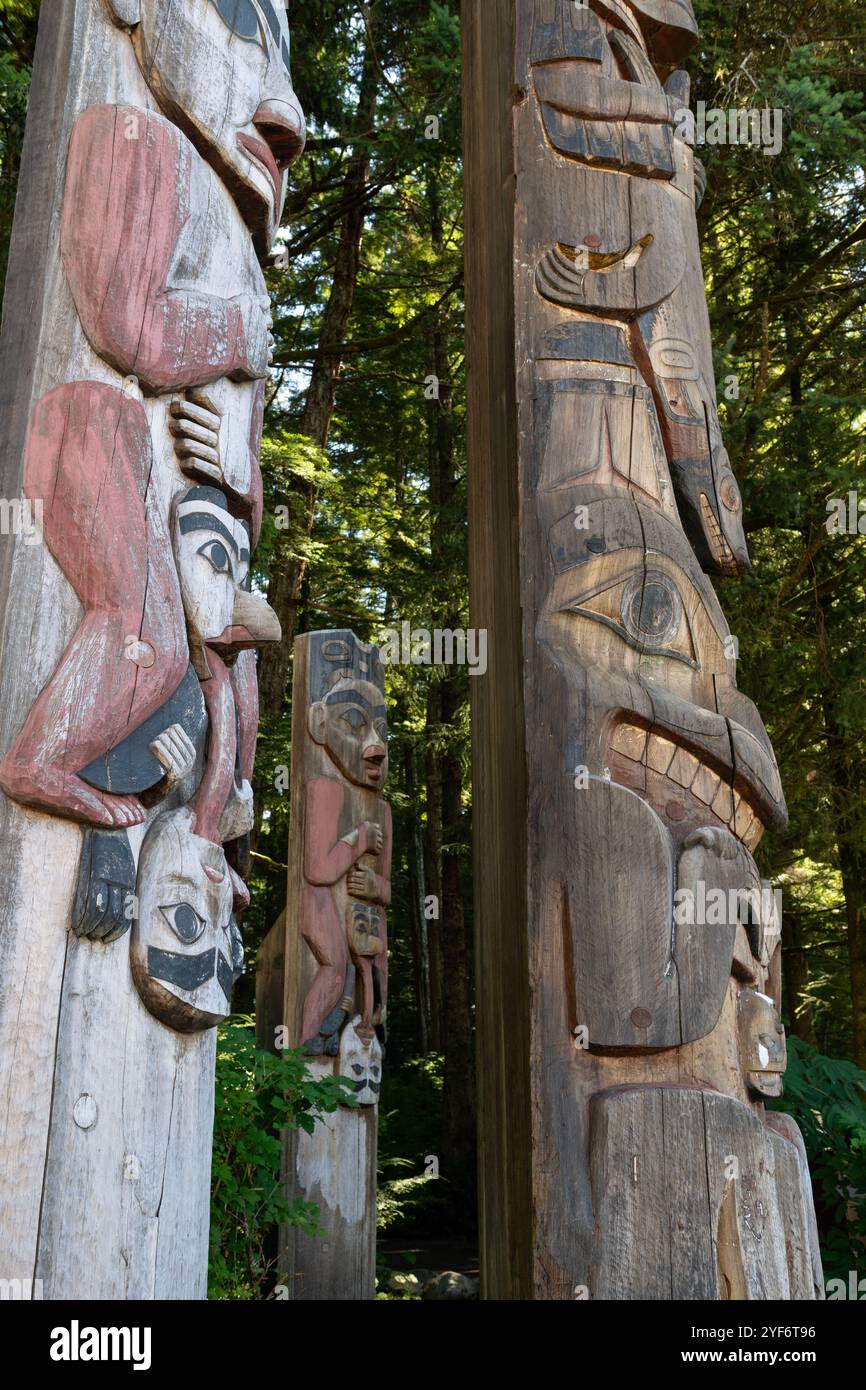

In the misty, verdant embrace of the Pacific Northwest, where ancient forests meet the restless sea, stand silent, majestic storytellers. Carved from the heartwood of monumental cedar, these towering sentinels – the totem poles of the Tlingit and Haida peoples – are far more than mere artistic expressions. They are living archives, monumental genealogies, and profound testaments to resilience, tradition, and an unbreakable connection to land and lineage. Their very presence speaks of a cultural heritage that, despite immense pressure, has not only endured but is experiencing a powerful, vibrant resurgence.

The tradition of carving totem poles among the Tlingit and Haida, two of the most prominent Indigenous nations of the Northwest Coast, stretches back millennia. These poles, known as gháay in Haida or ḵutaan in Tlingit, are not religious idols to be worshipped, but rather powerful visual narratives. They chronicle family histories, clan crests, significant events, and ancient myths, serving as mnemonic devices that reinforce cultural knowledge and social structures. "Each pole is like a book," explains a contemporary Haida carver, "it tells a story that we carry in our blood, a story that connects us to our ancestors and to the land."

The types of poles vary, each serving a distinct purpose. Memorial poles commemorate deceased chiefs or prominent individuals, often featuring their crests and significant life events. Mortuary poles traditionally contained the remains of the deceased in a box at the top, while house frontal poles were integrated into the very structure of a longhouse, often serving as the main entrance, their carved figures welcoming or warning visitors. Welcome poles, typically placed near the water’s edge, greeted guests arriving by canoe, while rarer shame poles were erected to publicly denounce individuals or groups who had committed a significant offense, often remaining until restitution was made. Each pole, regardless of its specific function, was a declaration of identity, status, and rights.

The artistry inherent in these poles is deeply rooted in the distinctive Northwest Coast "Formline" art style. This intricate system of design, characterized by its flowing, curvilinear lines, ovoid shapes, and U-forms, is used to depict stylized animals, mythical beings, and human figures. Every element within a carving has meaning, often representing crests that belong to specific clans – such as the Raven, Eagle, Bear, Wolf, Killer Whale, or Beaver. The choice of crests and their arrangement on a pole is never arbitrary; it is carefully chosen to reflect the specific lineage, privileges, and stories of the family or individual commissioning the pole. The figures are often interlocking or superimposed, creating a dynamic visual narrative that must be "read" from bottom to top or top to bottom, depending on the story being told.

The material of choice for these monumental carvings is the Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata), a tree revered for its towering height, straight grain, and natural resistance to rot. Its soft, yet durable wood makes it ideal for carving, allowing for the deep cuts and intricate details characteristic of Tlingit and Haida art. The process of creating a pole is a profound undertaking, steeped in ceremony and collaboration. It begins with the careful selection of a suitable tree, followed by rituals to honor the tree’s spirit. Once felled, the log is painstakingly moved, often over long distances, to the carving shed.

Traditional carving tools included specialized adzes – elbow adzes for deep cuts and D-handled adzes for smoothing – and various chisels made from bone, stone, or later, iron. These tools, wielded with incredible precision, allowed carvers to shape the massive logs into vibrant, expressive forms. The work is arduous and time-consuming, often taking a team of master carvers and apprentices many months, or even years, to complete a single pole. Once carved, the poles are meticulously painted with natural pigments – black from charcoal, red from ochre or iron oxide, and blue-green from copper carbonate – mixed with fish eggs or animal fats as binders, bringing the figures to life with striking contrast.

The culmination of the carving process is the raising of the pole, a monumental event often accompanied by a potlatch. The potlatch, a complex ceremonial feast, is central to Tlingit and Haida culture, serving as a legal and social institution where rights and privileges are publicly witnessed and validated through feasting, dancing, and the distribution of gifts. The raising of a new totem pole, often requiring the combined strength of an entire community using ropes, levers, and sheer determination, was the ultimate validation of the pole’s narrative and the family’s status. It was a public declaration, etched in cedar and celebrated with profound cultural significance.

However, this vibrant tradition faced a devastating assault with the arrival of European colonizers and the subsequent imposition of Canadian and American laws. From the late 19th century through the mid-20th century, Indigenous cultures across North America were systematically suppressed. For the Tlingit and Haida, the Potlatch Ban, enacted in Canada in 1884 (and similar policies in the US), was particularly destructive. This legislation, which remained in force until 1951, aimed to dismantle Indigenous governance, spiritual practices, and social structures. Carving, an integral part of potlatch ceremonies, diminished drastically. Many existing poles were stolen, sold to museums, or left to decay, while the knowledge of their creation was forced underground. Generations grew up without seeing new poles raised, and the vital intergenerational transfer of knowledge was severely disrupted. "There was a time when our poles stood silent, or fell to the ground, and we worried the stories would be lost with them," recounts an elder from Haida Gwaii, reflecting on this dark period.

Yet, the spirit of the cedar and the stories it held refused to be silenced. The lifting of the Potlatch Ban in 1951 marked a turning point, ushering in an era of cultural revitalization. A new generation of carvers, often learning from the few remaining elders who had held onto the knowledge, began to rekindle the flame. Visionaries like the legendary Haida artist Bill Reid and the equally influential Haida carver Robert Davidson played pivotal roles in this resurgence. Davidson, in particular, is celebrated for carving and raising the first new totem pole in his home village of Masset, Haida Gwaii, in 1969, an event that galvanized a community and inspired countless others. "That day, we didn’t just raise a pole; we raised our spirits, our culture, our future," Davidson once stated.

Today, Tlingit and Haida totem pole carving is experiencing a powerful renaissance. Master carvers like Wayne Price, Freda Diesing (whose legacy lives on through the Freda Diesing School of Northwest Coast Art), and many others are not only producing magnificent new poles but are also dedicated to training the next generation. Cultural centers and art schools, often run by Indigenous communities themselves, are vital hubs for this knowledge transfer, ensuring that the intricate techniques, the Formline design principles, and the profound cultural narratives are passed down.

Contemporary poles are now found in prominent locations globally, from museums and art galleries to universities and government buildings, serving as powerful ambassadors of Indigenous culture and resilience. They stand as monuments to survival, symbols of reconciliation, and affirmations of identity. Modern carvers often blend traditional methods with contemporary tools, using chainsaws for initial shaping before returning to the precision of adzes and chisels for detailed work. This pragmatic approach ensures that the art form can continue to thrive in the modern world while respecting its ancient roots.

The process of raising a pole continues to be a profound community event, often drawing thousands of onlookers and participants. These ceremonies are not just artistic unveilings; they are acts of cultural assertion, celebrations of community strength, and powerful affirmations of Indigenous sovereignty. New poles are often commissioned to mark significant events, such as the opening of a new building, a treaty signing, or to honor a specific individual, continuing their role as living historical records.

The Tlingit and Haida totem poles are more than just magnificent wooden sculptures. They are living narratives, breathing embodiments of a people’s history, spirituality, and enduring connection to their ancestral lands. From the ancient forests where the cedar grows, to the skilled hands that transform logs into monumental works of art, to the communities that gather to raise them, these poles embody a continuous cultural thread. They stand as powerful reminders that despite periods of immense hardship, the Tlingit and Haida peoples have maintained their distinct identities and traditions. As new poles continue to rise against the backdrop of the Pacific Northwest, they not only honor the past but also carve a path for a vibrant, self-determined future, ensuring that the stories of the cedar will continue to be told for generations to come.