Echoes of the Land: Unraveling the Elegant Complexity of Tlingit Grammar

In the misty fjords and ancient forests of Southeast Alaska and parts of Yukon and British Columbia, a language of profound depth and intricate beauty echoes through generations. Tlingit (Lingít), the language of the Lingít people, is more than just a means of communication; it is a living testament to a unique worldview, a sophisticated lens through which its speakers have understood and interacted with their environment for millennia. Yet, like many Indigenous languages globally, Tlingit faces the immense challenge of revitalization, with fewer than 200 fluent speakers remaining. Understanding its grammar, therefore, is not merely an academic exercise, but a vital step in appreciating the enduring legacy and potential future of a language that truly sings the land.

At first glance, Tlingit grammar can appear daunting to a speaker of English. Where English relies heavily on word order and prepositions to convey meaning, Tlingit operates on fundamentally different principles, particularly its polysynthetic and ergative-absolutive structure. "Our language is not just words; it’s a map to our soul, a guide to how we see the world," once remarked a Tlingit elder, a sentiment profoundly reflected in the very architecture of its sentences.

The Ergative Heartbeat: A Different Dance of Agency

Perhaps the most striking feature of Tlingit grammar is its ergative-absolutive case system. In English, a subject is typically marked in the same way, whether it performs an action (the agent of a transitive verb) or simply exists (the subject of an intransitive verb). For example, "He walks" and "He sees the bear." "He" is the subject in both.

Tlingit, however, distinguishes between these roles. The agent of a transitive verb (the one doing something to something else) is marked differently from the subject of an intransitive verb (the one just doing something) and the patient of a transitive verb (the one being acted upon). This is the essence of ergativity. The absolutive case marks the subject of an intransitive verb and the direct object of a transitive verb, while the ergative case marks the subject of a transitive verb.

Consider the Tlingit example:

- G̱ooch yatee. (The wolf is sleeping.) – G̱ooch (wolf) is in the absolutive case.

- G̱ooch-ch’ áx̱ tlákdu. (The wolf-ERGATIVE killed the deer.) – G̱ooch-ch’ (wolf-ERGATIVE) is marked differently, highlighting its active role in a transitive action, while áx̱ (deer) is in the absolutive.

This system places a unique emphasis on the relationship between an action, its agent, and its recipient. It’s not just about who did what, but how agency is distributed within the event. As linguist Dr. James Crippen notes, "Tlingit grammar prioritizes the outcome of an action as much as, if not more than, the initiator." This focus on the affected party and the nature of the action itself provides a fascinating window into Tlingit conceptualization.

The Verb: The Dynamic Core of Tlingit Expression

If Tlingit has a grammatical heart, it is undoubtedly the verb. Tlingit is a polysynthetic language, meaning that individual words, particularly verbs, can be incredibly complex, incorporating multiple morphemes (meaningful units) to express what might take an entire phrase or sentence in English. A single Tlingit verb can convey information about the subject, object, aspect, mood, direction, location, and even the shape or state of the object being acted upon.

Imagine a Tlingit verb as a meticulously constructed edifice, built from a core stem and adorned with a precise sequence of prefixes and suffixes. Linguists like Jeff Leer have identified a highly structured "verb template" with up to 12 or more potential positions for prefixes, each slot conveying a specific grammatical category.

Let’s break down some of these crucial elements:

-

Classifiers: One of the most intriguing aspects of Tlingit verbs is the use of "classifiers" or "translocational prefixes." These are morphemes attached to the verb stem that specify the shape, state, or nature of the object being moved or acted upon. For example, there are different classifiers for:

- A long, rigid object (e.g., a stick, a gun)

- A round, compact object (e.g., a rock, a ball)

- A liquid (e.g., water, oil)

- A mass of material (e.g., dirt, snow)

- An animate being

So, "to carry a stick" uses a different verb form than "to carry a rock," and both are different from "to carry water." This forces speakers to be incredibly precise about the physical properties of objects in motion, a reflection of a culture deeply attuned to its material world.

-

Aspect and Mode (Not Tense): Unlike English, which heavily relies on tenses (past, present, future) to mark when an action occurred, Tlingit primarily uses aspect and mode. Aspect describes the nature of an action’s completion, duration, or repetition (e.g., ongoing, completed, habitual, beginning, ending). Mode describes the speaker’s attitude towards the action (e.g., declarative, interrogative, imperative, optative, hypothetical).

For instance, instead of a simple "I ate," Tlingit might convey "I have finished eating" (perfective aspect), or "I am in the process of eating" (imperfective aspect). This provides a more nuanced understanding of the process of an event rather than just its chronological placement. This can be challenging for English speakers to grasp, as it requires a shift in how one conceptualizes time and action.

-

Directional Prefixes: Tlingit verbs are rich with prefixes that indicate precise direction and motion. Beyond simple "to" or "from," Tlingit can specify motion "upriver," "downriver," "to the shore," "away from the shore," "inland," "seaward," "through an opening," "around a corner," and many more. This hyper-specificity is another reflection of a people whose lives were intimately connected to their environment and its unique geography of waterways, mountains, and coastlines.

Nouns and Noun Phrases: Simplicity with Precision

While verbs are the stars of Tlingit grammar, nouns play a supporting, yet crucial, role. Tlingit nouns are relatively simple compared to their verb counterparts, lacking grammatical gender or complex declensions. However, they demonstrate precision in other ways:

-

Possession: Inalienable vs. Alienable: Tlingit distinguishes between two types of possession:

- Inalienable possession refers to things that are inherently part of something or someone and cannot be separated from them (e.g., body parts, family relations, inherent qualities). These are typically expressed by directly attaching a possessive prefix to the noun stem. For example, aaw (hand) becomes xa-aaw (my hand).

- Alienable possession refers to things that can be owned or separated (e.g., a canoe, a house, a tool). These are expressed using a separate possessive pronoun or particle. For example, xa-yát (my child) uses the inalienable form, while xat duwaan áa xát daat (my canoe) uses an alienable construction. This distinction highlights cultural values regarding kinship and inherent belonging versus acquired property.

-

Demonstratives: Tlingit possesses a rich system of demonstratives (words like "this," "that") that encode not only distance but also visibility, motion, and even vertical position. There are distinct words for "this (visible and close)," "that (visible and far)," "that (invisible but known)," "this (moving toward speaker)," "that (moving away from speaker)," "that (up high)," "that (down low)," and so on. This remarkable precision reinforces the Tlingit emphasis on spatial awareness and the dynamic nature of the world.

Sentence Structure: Flexibility and Emphasis

While English generally adheres to a strict Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) word order, Tlingit exhibits more flexibility. A common pattern is Verb-Subject-Object (VSO), but SVO and OVS are also possible, often used for emphasis or stylistic variation. The extensive information encoded within the verb itself means that word order is less critical for basic comprehension and can be manipulated to highlight specific elements of the sentence.

The Phonological Canvas: Sounds That Speak Volumes

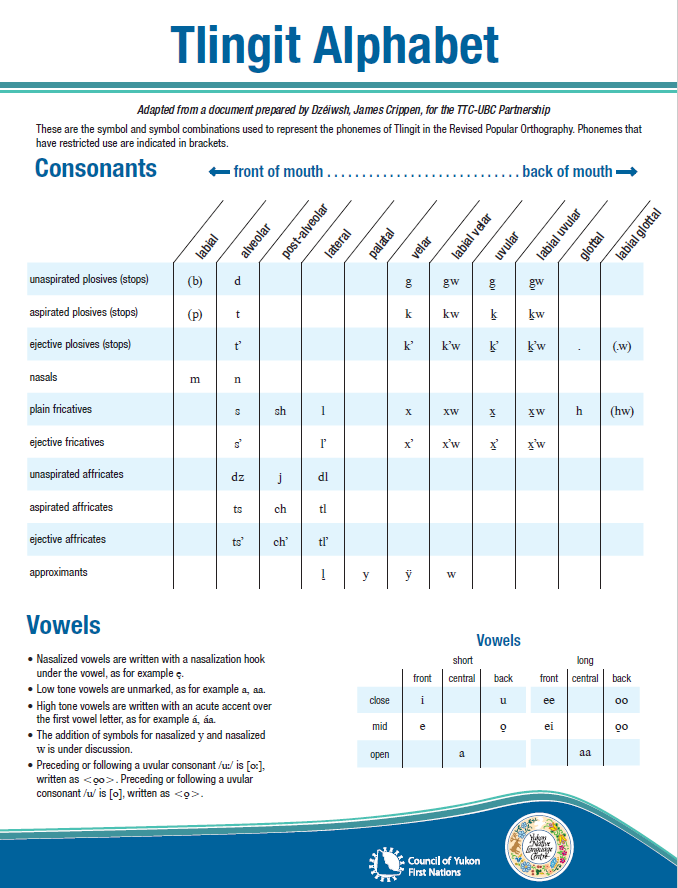

While not strictly grammatical, the phonology of Tlingit contributes significantly to its unique character and influences how its grammar is perceived. Tlingit is known for its rich inventory of consonants, including:

- Glottalized consonants: Sounds produced with a simultaneous closure of the vocal cords (e.g., kʼ, tʼ, chʼ).

- Ejectives: Sounds produced with a burst of air from the glottis (similar to glottalized consonants but more forceful).

- Lateral fricatives: Sounds like the "ll" in Welsh, produced by air flowing over the sides of the tongue (e.g., ḻ, ḻ’).

- Uvular consonants: Sounds produced at the back of the throat (e.g., ḵ, g̱).

These sounds give Tlingit a distinctive, sometimes guttural, quality that can be challenging for non-native speakers. It’s important to note, however, that Tlingit is not a tonal language like Mandarin Chinese. While pitch can play a role in emphasis, it does not distinguish word meanings in the same systematic way.

Grammar as a Cultural Lens: A Worldview Embodied

Beyond the linguistic mechanics, the grammar of Tlingit serves as a profound cultural lens. The emphasis on aspect over tense, the detailed classifiers, and the precise directional prefixes all point to a worldview deeply rooted in observation, process, and the interconnectedness of all things. The language encourages speakers to be highly attentive to the state, location, and motion of objects and beings within their environment.

"Learning Tlingit verbs is like learning to paint with an incredibly rich palette," explains X̱ʼunei Lance Twitchell, a prominent Tlingit language advocate and professor. "Every stroke, every prefix, adds a layer of meaning that forces you to think about the world in a different way." The ergative system, for example, subtly shifts focus to the result or patient of an action, perhaps reflecting a cultural value that considers the impact of an action as much as the actor’s intent.

Revitalization: The Future of Lingít

The beauty and complexity of Tlingit grammar highlight the immense loss that occurs when a language fades. Each unique grammatical structure represents centuries of accumulated knowledge, cultural nuance, and a distinct way of knowing the world. Recognizing this, the Tlingit people, along with dedicated linguists and educators, are engaged in a passionate and urgent struggle for language revitalization.

Efforts range from immersive language camps and master-apprentice programs, where fluent elders pass on their knowledge to dedicated learners, to the development of comprehensive dictionaries, grammars, and online learning resources. The work of linguistic giants like Richard and Nora Dauenhauer, who meticulously documented Tlingit language and oral literature for decades, provides an invaluable foundation for these modern efforts.

"Every Tlingit word carries the weight of generations, the wisdom of our ancestors," says a young Tlingit learner. "To speak it is to walk in their footsteps, to keep their spirit alive." The challenge is immense, requiring sustained dedication and resources, but the commitment of the Tlingit community is unwavering.

In conclusion, Tlingit grammar is a marvel of linguistic engineering, a system that challenges conventional notions of how language functions. Its ergative structure, verb-centric polysynthesis, and nuanced systems of aspect, classification, and direction offer a glimpse into a worldview shaped by the unique environment and rich cultural heritage of the Lingít people. As the struggle for its revitalization continues, understanding and appreciating the elegant complexity of Tlingit grammar becomes not just an academic pursuit, but an act of profound respect for a language that truly embodies the echoes of the land and the enduring spirit of its people.