Echoes in Cedar and Thread: The Enduring Art of the Tlingit People

In the rugged embrace of Southeast Alaska, where ancient rainforests meet the icy breath of glaciers and the restless Pacific, lives a people whose artistic heritage is as profound and intricate as the landscape itself. The Tlingit, an Indigenous nation whose history stretches back millennia, have long expressed their worldview, identity, and spirituality through a vibrant and sophisticated artistic tradition. Far from mere decoration, Tlingit traditional arts are a living language, a repository of history, law, and lineage, and a powerful testament to resilience in the face of adversity.

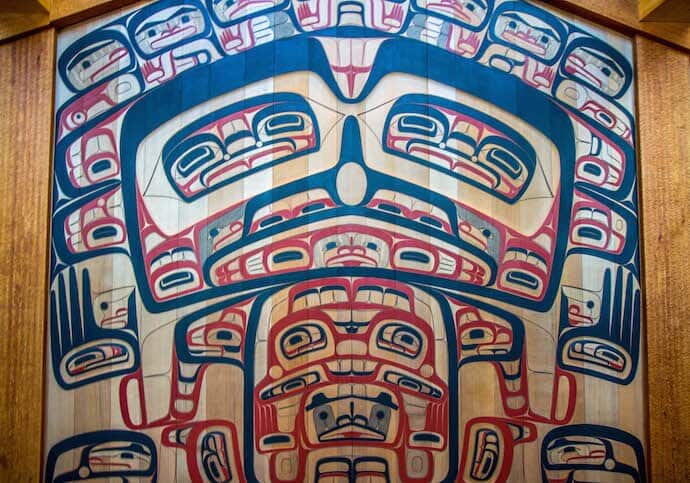

At the heart of Tlingit visual expression lies "formline," a unique artistic system that defines much of Northwest Coast Indigenous art. It is a precise and complex aesthetic grammar characterized by continuous, flowing lines that swell and diminish, creating ovoids, U-forms, and S-forms. These shapes, often rendered in black, red, and blue-green, interlock and overlap, transforming into highly stylized depictions of animals, spirits, and mythical beings. Every element within a formline composition holds meaning, and the negative spaces are as important as the positive, creating a dynamic interplay of balance and tension.

"Formline is not just about drawing a line; it’s about understanding the energy and spirit that flows through everything," explains acclaimed Tlingit artist Preston Singletary, whose work often bridges traditional forms with contemporary glass art. "It’s a system that allows us to tell stories, to show our clan crests, and to connect with our ancestors. It’s a language that everyone here understands." This intricate system ensures that even a small detail, like an eye within a wing or a hand within a tail, can represent an entire creature, inviting the viewer to decipher the layers of meaning.

The primary medium for Tlingit artistic expression has historically been wood, particularly the abundant and easily carvable cedar of the temperate rainforest. Towering totem poles, perhaps the most iconic symbol of Northwest Coast art, stand as monumental narratives. These are not objects of worship, but rather heraldic devices, memorial columns, or house frontal poles that recount clan histories, honor deceased chiefs, or commemorate significant events. Each figure carved into the pole—be it a raven, bear, eagle, or whale—represents a specific clan or a story belonging to that lineage, serving as a powerful visual mnemonic for oral traditions.

Beyond the monumental, Tlingit wood carving extends to a myriad of functional and ceremonial objects. Elaborately carved masks, often depicting transforming beings caught between human and animal forms, were central to ceremonies and dances, allowing wearers to embody spirits or ancestors. Bentwood boxes, ingeniously crafted from a single plank of cedar steamed and folded, were used for storage of valuables, food, and regalia. Their surfaces were often adorned with formline designs, transforming utilitarian objects into works of art. Canoes, vital for travel, trade, and hunting, were themselves masterworks of design and engineering, combining sleek functionality with carved and painted bows and sterns.

But Tlingit artistry is by no means limited to wood. Weaving, particularly the renowned Chilkat weaving, represents another pinnacle of their artistic achievement. Chilkat blankets, or "Naaxiin," are distinctive for their curvilinear formline designs rendered in a unique twining technique that allows for curved and circular patterns in textiles – a feat rarely achieved in weaving. Made from mountain goat wool and shredded cedar bark, these ceremonial robes shimmer with the movement of the wearer, the fringe swaying like the dancer’s hair. Each blanket tells a story or displays a clan crest, signifying the wearer’s identity and status.

"The Chilkat blanket is a living being," says master weaver Lily Hope, a Tlingit artist dedicated to revitalizing this complex art form. "It breathes with the dancer, and the designs hold the spirit of our ancestors. Learning to weave is not just about technique; it’s about connecting to that ancestral knowledge, about bringing something back to life." The immense time and skill required for a single Chilkat blanket—often taking a year or more to complete—reflects its profound cultural value.

Another significant weaving tradition is Ravenstail, characterized by its geometric patterns and typically used for dance aprons, tunics, and pouches. While Chilkat weaving is often associated with the later periods of Tlingit art, Ravenstail is believed to be an older form, showcasing a different aesthetic but equally demanding precision.

Beyond weaving, Tlingit artists also excelled in metalwork, particularly in silver and copper. Bracelets, rings, and ceremonial daggers were intricately engraved with clan crests and formline designs. "Coppers," large shield-shaped plates of hammered copper, were among the most valuable possessions, exchanged or broken during potlatches to demonstrate wealth and status, embodying the Tlingit economic system and social structure. Basketry, made from spruce roots, and beadwork on ceremonial garments further illustrate the breadth of Tlingit artistic ingenuity.

Crucially, Tlingit art is inextricably linked to the social and spiritual fabric of the community. It functions as a visual manifestation of the clan system, which is based on a dual moiety structure (Raven and Eagle). Every Tlingit belongs to one of these moieties, and within them, to specific clans. Art displays these affiliations: a totem pole outside a clan house, a crest on a button blanket, or a mask used in a ceremony all serve to affirm identity, lineage, and connection to the land and its resources.

The Potlatch, a grand ceremonial feast central to Northwest Coast cultures, served as the primary venue for the display and validation of Tlingit art. During these elaborate gatherings, art objects were commissioned, created, displayed, and often given away or destroyed, all to mark significant life events – a marriage, a naming ceremony, a death, or the raising of a totem pole. The very act of creating and displaying art was a form of asserting wealth, status, and rights, ensuring the continuity of cultural knowledge and social order.

However, this rich artistic and cultural heritage faced a severe threat during the colonial period. Missionaries and government agents, misunderstanding the profound significance of Tlingit ceremonies, moved to suppress Indigenous cultural practices. The infamous Potlatch Ban, enacted by the Canadian government in 1884 and later mirrored in some U.S. policies, forced Tlingit art and culture underground. Many priceless artifacts were confiscated, sold, or destroyed, and the intergenerational transmission of knowledge was severely disrupted. Children were sent to boarding schools, where their language and cultural practices were forbidden.

Despite these efforts to eradicate Indigenous identity, Tlingit art endured. Knowledge was passed on in secret, designs were remembered, and the spirit of creativity persisted. The lifting of the Potlatch Ban in the mid-20th century marked a turning point, ushering in an era of cultural revitalization.

Today, Tlingit traditional arts are experiencing a powerful resurgence. Organizations like the Sealaska Heritage Institute in Juneau have been pivotal in this revival, establishing language programs, cultural festivals like Celebration, and art mentorships. Master artists, often in collaboration with museums and cultural institutions, are actively teaching younger generations, ensuring that the intricate techniques and profound meanings of Tlingit art are not lost. Apprenticeships are common, with elders passing down knowledge directly to students, much as it was done for centuries.

Contemporary Tlingit artists are not merely replicating the past; they are building upon it. While deeply rooted in traditional formline and techniques, many artists are exploring new materials and media, from glass and metal to digital art and photography, infusing ancient aesthetics with modern sensibilities. This innovation demonstrates the living, evolving nature of Tlingit art – a tradition that honors its roots while looking to the future.

"Our art is our identity. It’s how we connect to our past, how we express who we are today, and how we teach our children for tomorrow," says Rosita Worl, a prominent Tlingit anthropologist and president of the Sealaska Heritage Institute. "It is a testament to the strength and resilience of our people that these art forms not only survived but are now flourishing."

From the majestic cedar poles that stand silent vigil over the Alaskan landscape to the intricately woven threads of a Chilkat blanket, Tlingit traditional arts are more than just beautiful objects. They are powerful narratives, living histories, and profound expressions of a vibrant culture that continues to thrive. They remind us that art, in its purest form, is not just something we see, but something that lives, breathes, and carries the spirit of a people across generations. As the Tlingit people continue to carve, weave, and create, they ensure that the echoes in cedar and thread will resonate for millennia to come.