Echoes in the Earth and Sky: The Ingenuity of Traditional Native American Homes

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

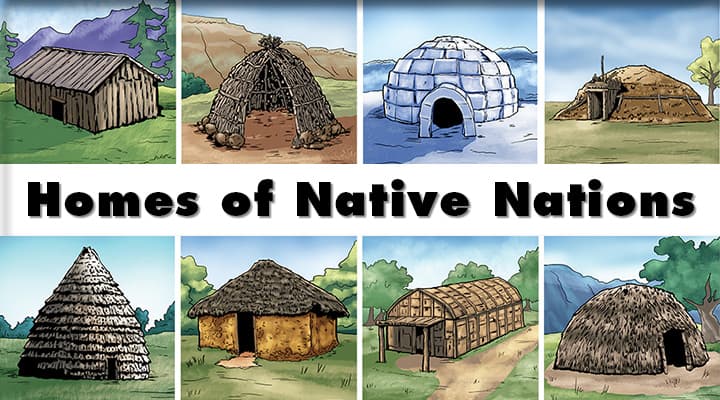

From the snow-swept plains of the Arctic to the sun-baked deserts of the Southwest, and the dense forests of the Northeast, the traditional homes of Native American peoples stand as profound testaments to human ingenuity, cultural depth, and an unparalleled understanding of the natural world. Far from the simplistic, often monolithic representations found in popular culture, Indigenous dwellings were incredibly diverse, meticulously designed, and deeply intertwined with the spiritual and social fabric of each distinct nation. They were not merely shelters; they were living extensions of the land, crafted from its bounty and shaped by its demands, echoing the wisdom of generations.

"To understand a people, you must understand their home," writes architect and scholar Frank Lloyd Wright, a sentiment that resonates deeply when exploring the architectural heritage of Native Americans. Each structure, whether a portable hide tent or a multi-story stone complex, reflects specific environmental conditions, available resources, and the unique cultural practices, mobility patterns, and social structures of its inhabitants. This article delves into the remarkable diversity and sophisticated design principles behind some of the most iconic traditional Native American housing types, revealing their enduring lessons in sustainability, community, and harmony with nature.

The Nomadic Ingenuity: Adaptability on the Move

For nations whose survival depended on following migratory game or seasonal resources, mobility was key. Their homes needed to be easily dismantled, transported, and reassembled, yet robust enough to withstand harsh elements.

The Tipi (Tepee): Symbol of the Plains

Perhaps the most globally recognized Native American dwelling, the Tipi (often spelled Tepee), is synonymous with the Plains Nations such as the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfoot. More than just a tent, the tipi was a highly sophisticated, aerodynamic structure perfectly adapted to the vast, windy plains.

Constructed from a conical framework of lodgepoles covered with stitched bison hides (later canvas), the tipi’s design was a marvel of engineering. Its sloped sides provided excellent stability against strong winds, while an adjustable smoke flap at the top allowed for ventilation and smoke escape from an indoor fire, even in inclement weather. The interior was surprisingly spacious and warm in winter, cool in summer, thanks to an inner liner that created an insulating air pocket.

"The tipi was not just a dwelling; it was a universe," explains a contemporary Lakota elder. "The poles reached for the sky, connecting us to the Creator, and the circular base grounded us to Mother Earth." Its portability was paramount for nations following bison herds. A large tipi could be taken down and packed onto a travois (a A-frame sled pulled by horses or dogs) in less than an hour, ready for the next encampment. The tipi embodied the nomadic spirit: adaptable, resilient, and deeply spiritual.

The Wigwam: Northeastern Versatility

In the dense forests of the Northeast and Great Lakes regions, nations like the Algonquin, Ojibwe, and Wampanoag developed the Wigwam (or Wìkiwam), a domed or conical dwelling that was also highly adaptable. Unlike the tipi’s rigid poles, wigwams were built with flexible saplings bent into an arch, forming a dome-like frame. This framework was then covered with sheets of bark (especially birch bark, prized for its waterproofing and lightness), woven mats, or animal hides.

Wigwams varied in size and shape, from small, single-family structures to larger, oval-shaped homes that could accommodate multiple families. While less mobile than the tipi, they could be dismantled and moved seasonally, or simply re-covered with fresh materials. Their natural insulation properties made them effective against the region’s cold winters and humid summers. The wigwam represented a harmony with the forest, utilizing its renewable resources for shelter.

Sedentary Settlements: Enduring Structures, Deep Roots

For nations with stable food sources, such as agriculture or abundant fishing, permanent or semi-permanent dwellings became the norm, leading to the development of remarkable architectural complexes.

The Longhouse: Communal Living in the Northeast

The Longhouse was the signature dwelling of the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee), including the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations, as well as other groups like the Huron. These impressive structures were true communal homes, reflecting the matrilineal and highly organized social structure of the Iroquois.

Built from a sturdy framework of saplings and posts, covered with elm bark shingles, longhouses were rectangular, tunnel-like buildings that could stretch for hundreds of feet. A typical longhouse might be 80 to 200 feet long, 18 to 20 feet wide, and 18 to 20 feet high. Inside, a central corridor contained multiple hearths, shared by families living in compartments along the walls. Each longhouse housed several related families, often descended from a common clan mother.

The longhouse was more than just a home; it was the heart of Iroquois society, serving as a residence, a meeting place, and a spiritual center. Its design fostered community, cooperation, and the sharing of resources. As one historian noted, "The longhouse was a living metaphor for the Iroquois Confederacy itself – many nations under one roof, united by a common purpose."

The Hogan: Navajo Earth and Spirit

In the arid Southwest, the Hogan is the traditional dwelling of the Navajo (Diné) people, a structure deeply imbued with spiritual significance and a profound connection to the earth. There are two primary types: the male (forked-stick) hogan and the female (circular, crib-style log) hogan.

The most common female hogan is a circular or hexagonal structure built from logs or stone, insulated with earth packed over the walls and roof. The door traditionally faces east, to welcome the morning sun and its blessings. Inside, the hogan is a single, open room, with a central fire pit and a smoke hole at the top. The earth construction provides excellent insulation against the extreme desert temperatures, keeping it cool in summer and warm in winter.

The Hogan is considered a living entity, a sacred space where ceremonies are performed, and daily life unfolds in harmony with the cosmos. It represents the universe in miniature, with the floor as Mother Earth and the roof as Father Sky. Every aspect of its construction and orientation is symbolic, reflecting Navajo cosmology and traditions.

The Pueblo: Enduring Desert Cities

The term "Pueblo" refers both to the people (e.g., Hopi, Zuni, Taos, Acoma) and their multi-story, apartment-like villages built from adobe (sun-dried earth bricks) or stone. Found throughout the Southwest, these structures represent some of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America, with origins dating back over a thousand years to the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi).

Pueblos were often built into cliff faces or on mesas for defensive purposes, and their communal nature allowed for shared resources and protection. They were typically multi-storied, with rooms accessed via ladders to upper levels, and often featured communal courtyards and subterranean ceremonial chambers known as kivas. The thick adobe walls provided exceptional insulation, regulating interior temperatures against the harsh desert climate.

The architecture of the Pueblo peoples is a testament to sophisticated urban planning and a deep understanding of sustainable building. Their homes were not just individual dwellings but integrated communities, embodying a philosophy of collective living and a reverence for the land that provided their materials.

The Earthlodge: Plains Sedentary Life

While some Plains nations were nomadic, others, like the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Pawnee, were sedentary agriculturalists who built substantial Earthlodges. These large, circular homes were semi-subterranean, with a deep pit forming the base, over which a sturdy timber frame was erected. This frame was then covered with layers of willow branches, grass, and a thick layer of earth, providing exceptional insulation.

Earthlodges were remarkably durable, lasting for decades, and could house multiple families, often 20 to 40 people. A central fire pit provided warmth, with a smoke hole at the top. The design offered protection from both the extreme cold of winter and the intense heat of summer, as well as strong winds. They represent a blend of the communal living seen in longhouses with the earth-based construction of hogans, tailored for the specific conditions of the riverine plains.

Other Notable Dwellings: A Glimpse into Regional Diversity

The vastness of North America necessitated countless other ingenious housing solutions:

- Chickee (Seminole & Miccosukee): In the hot, humid Everglades of Florida, the Seminole and Miccosukee peoples developed the Chickee, an open-sided dwelling with a raised platform floor and a thatched palmetto roof. This design allowed for maximum air circulation, protection from flooding, and a cool refuge from the subtropical heat and insects.

- Igloo (Inuit): In the Arctic, the Inuit people mastered the art of building temporary shelters from snow and ice. The Igloo (or Iglu) is a dome-shaped structure built from precisely cut snow blocks laid in a spiral. Snow, surprisingly, is an excellent insulator. With a small entrance tunnel trapping cold air, an igloo could be surprisingly warm inside, often reaching above freezing temperatures even when outside temperatures plummeted.

- Wikiup (Great Basin/Southwest): Simpler than the wigwam, the Wikiup was a conical or domed brush shelter used by groups like the Paiute and Apache. Made from a framework of branches covered with brush, grass, or bark, they were quick to construct and offered basic shelter, suitable for highly mobile groups in arid environments.

Enduring Lessons in Sustainability and Spirit

What unites these incredibly diverse housing types is not their form, but their underlying principles. They embody a profound respect for the environment, utilizing locally available, renewable resources with minimal waste. They are models of sustainability, built to last yet designed to return to the earth without harm when abandoned.

Moreover, Native American homes were rarely purely utilitarian. They were imbued with cultural meaning, spiritual significance, and often oriented to celestial bodies or sacred directions. The act of building was often a communal effort, reinforcing social bonds and shared responsibilities.

In a world grappling with climate change and the need for sustainable living, the wisdom embedded in traditional Native American housing offers invaluable lessons. They remind us that true architecture is not about conquering nature, but about collaborating with it; not about imposing rigid forms, but about adapting with grace; and not about isolated structures, but about homes that are deeply connected to community, culture, and the very spirit of the land. The echoes of these ancestral homes resonate today, reminding us of a time-honored path to living in harmony with the earth and sky.