Where Culture Meets Calculus: The Transformative Curriculum of Tribal Colleges and Universities

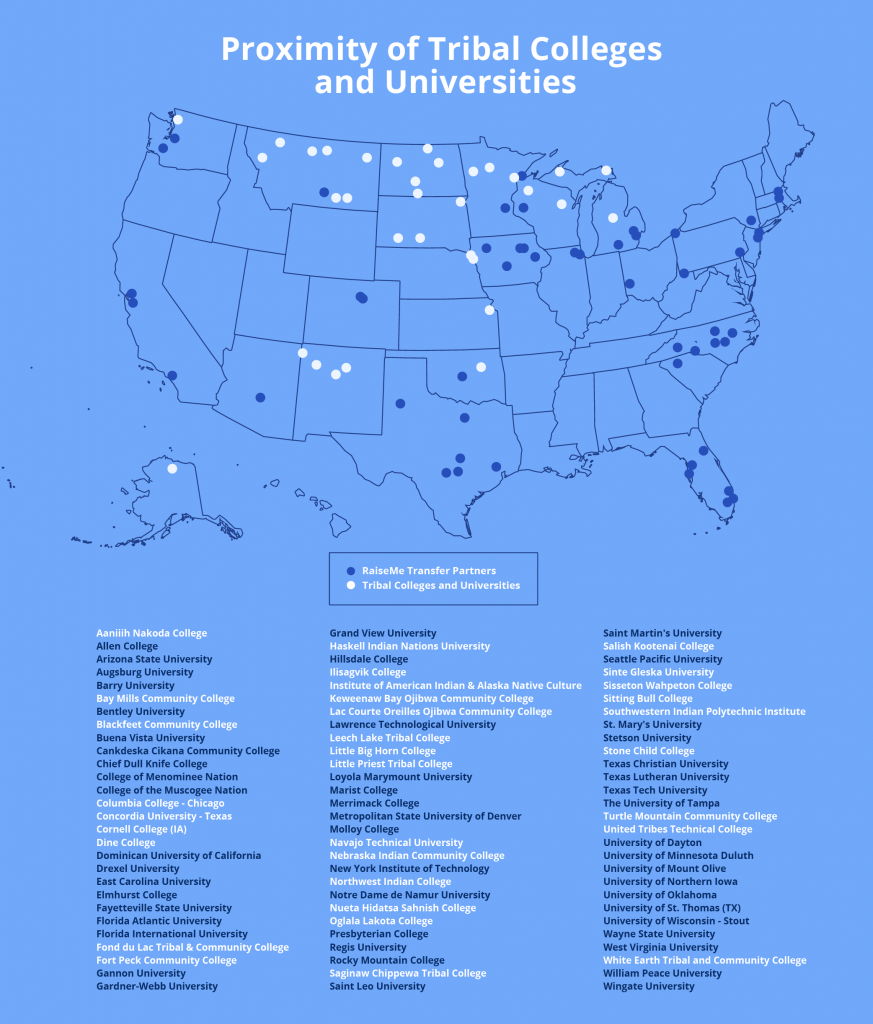

In the vast educational landscape of the United States, a unique constellation of institutions shines brightly, often outside the mainstream glare. These are the Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), some 35 institutions primarily located on or near reservations, serving Native American students and their communities. Far from being mere replicas of mainstream universities, TCUs offer a profound and distinctive curriculum, one that meticulously weaves together Western academic rigor with Indigenous knowledge, language, history, and cultural values. This is not just education; it is an act of cultural preservation, sovereignty, and community revitalization.

At their core, TCUs were born out of a critical need. For generations, Native Americans were subjected to assimilationist policies, often through boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian, save the man." Mainstream higher education, while offering opportunities, frequently overlooked or actively denigrated Indigenous perspectives. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as the self-determination movement gained momentum, tribal nations recognized that true sovereignty required control over their own education systems. They needed institutions that understood their unique challenges, celebrated their heritage, and prepared their citizens to lead their communities into the future on their own terms.

This foundational purpose directly informs the TCU curriculum, making it fundamentally different from its non-Native counterparts. "Education is the new buffalo," famously declared Dr. Henrietta Mann (Cheyenne/Arapaho), a revered elder and scholar in Indigenous education. This powerful metaphor underscores the idea that just as the buffalo sustained Plains tribes physically and spiritually, education – culturally relevant and tribally controlled – is now essential for survival, self-sufficiency, and cultural perpetuation.

The Pillars of Cultural Integration

The most striking feature of TCU curricula is its deep integration of Indigenous culture. This isn’t an add-on; it’s the very fabric of learning. While students pursue degrees in nursing, business, education, or STEM fields, they do so through a lens that acknowledges and respects their ancestral heritage.

One of the most vital components is language revitalization. Many Indigenous languages are critically endangered due to historical suppression. TCUs are on the front lines of reversing this trend. At institutions like Sinte Gleska University on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, the Lakota language is not just offered as a foreign language elective; it’s a core component of many degree programs. Students might study Lakota history in Lakota, or explore scientific concepts using traditional Lakota terminology. Faculty members are often fluent speakers, providing immersive learning environments that help students reconnect with their linguistic roots, a crucial link to cultural identity and traditional knowledge.

Beyond language, Indigenous history and governance are central. Unlike mainstream institutions where Native American history might be relegated to a single elective, at TCUs, it is foundational. Students learn about tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, traditional governance structures, and contemporary tribal nation building. This knowledge empowers them to understand their place in the world and prepares them for leadership roles within their own tribal governments and enterprises. Courses might delve into the specifics of a tribe’s origin stories, migration patterns, legal battles, and resilience in the face of adversity.

Bridging Traditional Knowledge and Modern Disciplines

Perhaps the most innovative aspect of TCU curricula is its ability to bridge traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and Indigenous science with Western academic disciplines. This concept is often referred to as "two-eyed seeing," a term coined by Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall, which means learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing and from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and to use both eyes together.

Consider environmental science or agriculture programs. While students learn about modern farming techniques, soil science, and ecological principles, they also study traditional Indigenous land management practices, sustainable harvesting methods, and the deep spiritual connection to Mother Earth. At institutions like Sitting Bull College in North Dakota, agricultural programs might focus on drought-resistant native plants or the reintroduction of traditional food systems, connecting food sovereignty directly to tribal health and economic development. This approach not only provides practical skills but also reinforces cultural values of stewardship and respect for the land.

In STEM fields, this integration is equally powerful. While a student at Navajo Technical University (NTU) in New Mexico might be studying advanced engineering or computer science, they are also encouraged to explore how traditional Navajo knowledge systems – which include sophisticated understandings of astronomy, architecture, and mathematics – can inform their modern studies. NTU, for example, offers a unique culinary arts program that blends modern techniques with traditional Navajo cooking, emphasizing nutrition and cultural foods.

For healthcare programs, the curriculum emphasizes culturally competent care. Students pursuing degrees in nursing or community health learn about traditional healing practices, the social determinants of health within Native communities, and how to navigate health disparities with sensitivity and understanding. This ensures that future healthcare providers are not only clinically skilled but also deeply empathetic to the cultural contexts of their patients.

Holistic Well-being and Community Development

TCUs also embrace a holistic approach to education, recognizing that academic success is intertwined with spiritual, emotional, and physical well-being. Counseling services, cultural ceremonies, and elder mentorship programs are often integral to the student experience. The curriculum extends beyond the classroom to active community engagement. Many programs incorporate service-learning, where students apply their knowledge to real-world challenges facing their tribal nations, from developing business plans for tribal enterprises to creating educational materials for local schools.

This community-centric focus is evident in business and entrepreneurship programs. While teaching standard business principles, TCUs often tailor the curriculum to the unique economic realities of reservations, focusing on tribal enterprises, sustainable economic development, and entrepreneurship that benefits the community rather than solely individual profit. Students learn about tribal gaming, resource management, and developing businesses that respect cultural values and contribute to tribal self-sufficiency.

Challenges and Resilience

Despite their vital mission and innovative curricula, TCUs face significant challenges. Chronic underfunding compared to mainstream institutions is a persistent issue. Many TCUs operate with limited resources, relying heavily on federal appropriations that often fall short of their needs. This impacts everything from faculty salaries and infrastructure to technology and student support services. Furthermore, TCUs often serve students who face unique socioeconomic barriers, including intergenerational trauma, poverty, and limited access to technology.

Yet, through it all, TCUs exhibit remarkable resilience. They are centers of hope and empowerment, producing graduates who are not only academically proficient but also culturally grounded and committed to their communities. They are reclaiming educational narratives, fostering a sense of pride and belonging, and preparing the next generation of leaders, educators, healthcare professionals, and innovators who will drive the future of their tribal nations.

The Future of Indigenous Education

The curriculum of Tribal Colleges and Universities represents a paradigm shift in higher education. It challenges the colonial legacy of knowledge dissemination by asserting the validity and importance of Indigenous ways of knowing. It demonstrates that academic excellence and cultural preservation are not mutually exclusive but, in fact, mutually reinforcing.

As TCUs continue to evolve, they serve as models for how education can be a tool for decolonization, healing, and self-determination. They prove that by rooting education in culture, language, and community, institutions can not only produce skilled graduates but also cultivate resilient, culturally vibrant, and sovereign nations. In a world increasingly recognizing the value of diverse perspectives, the innovative curriculum of TCUs stands as a powerful testament to the enduring strength and wisdom of Indigenous peoples.