Echoes in the Canyons: The Enduring Legacy of Ute Tribal Lands

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

The vast, rugged landscapes of the American West whisper stories of ancient peoples, of resilience etched into sandstone and pine. Among the loudest of these echoes are those of the Ute, a proud and enduring people whose history is inextricably linked to the mountains, mesas, and rivers of what is now Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. Their lands, once an expansive dominion, have been diminished by centuries of encroachment, yet they remain the bedrock of Ute identity, sovereignty, and a future built on self-determination.

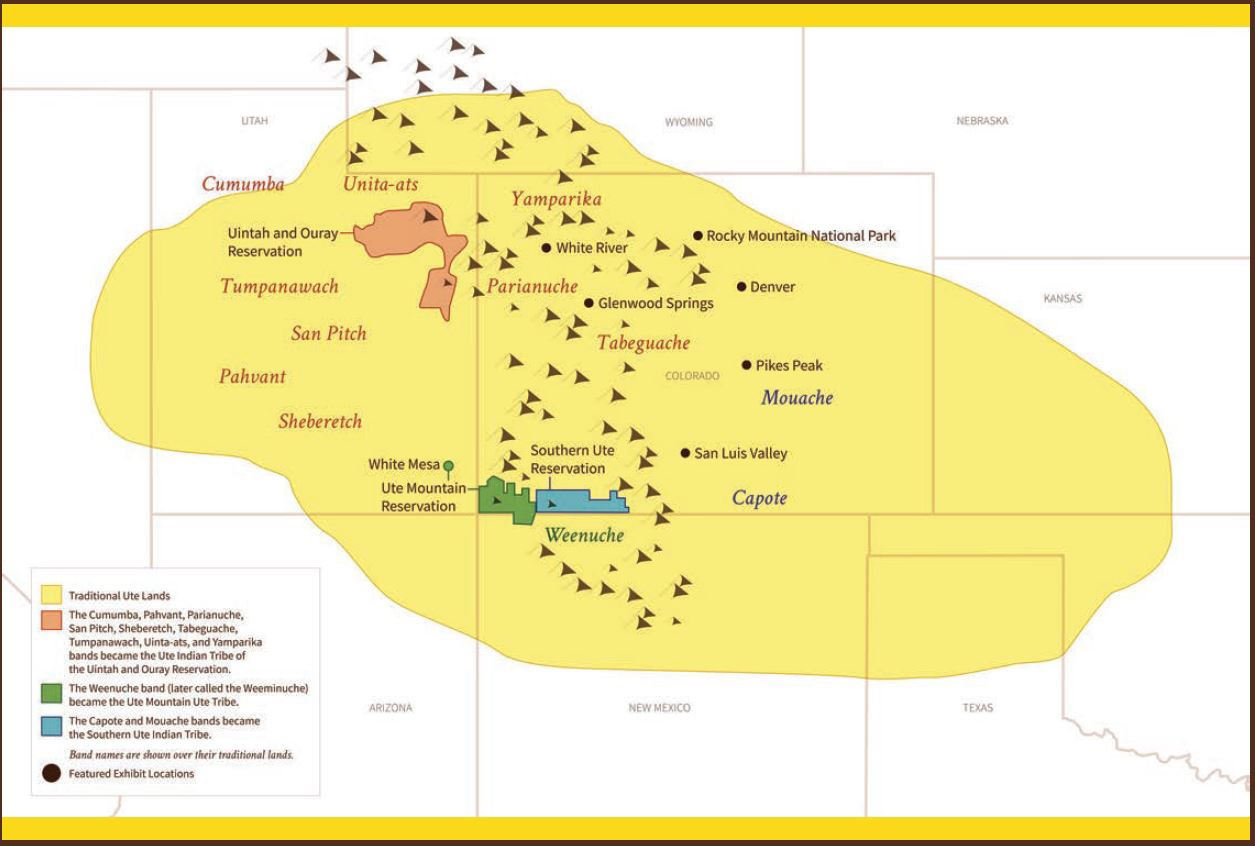

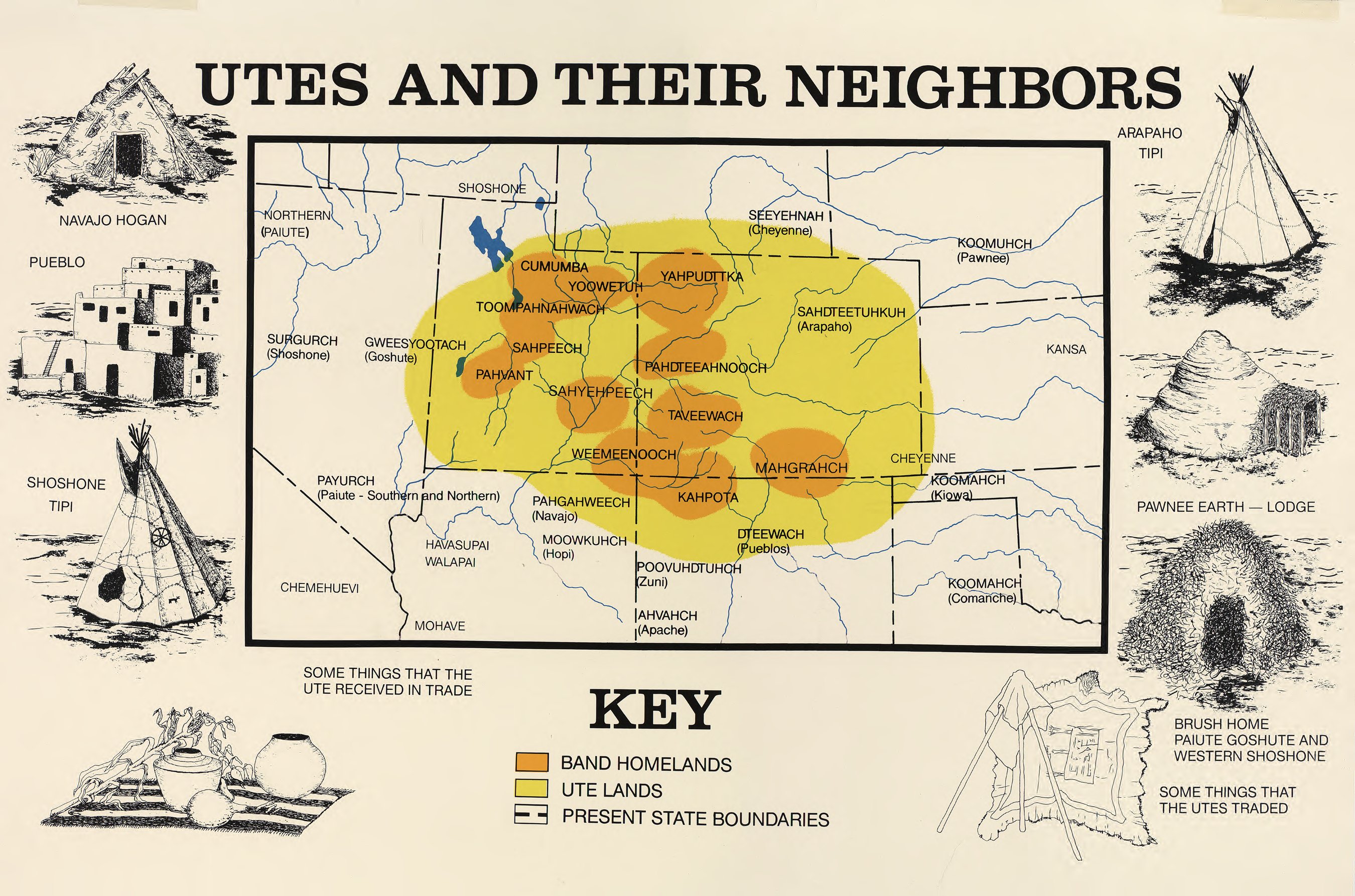

To truly understand the Ute is to understand their profound connection to the land. For millennia, the Nuche, "The People," as they call themselves, thrived across a territory that stretched from the Rocky Mountains’ eastern slopes to the Great Basin, and from southern Wyoming down into northern New Mexico. They were hunters and gatherers, skilled horsemen, intimately familiar with the rhythms of their environment. Their seasonal migrations followed game and ripening plants, their spirituality woven into every peak and valley. The land was not merely property; it was a living entity, a provider, a sacred trust passed down through generations.

"Our land is not just soil and rock; it is our history, our church, and our future," as one Ute elder recently put it, her voice resonant with the wisdom of her ancestors. "To protect it is to protect who we are, to ensure that the spirits of our people continue to walk here."

A Legacy of Loss: The Treaty Era and Its Aftermath

The arrival of European settlers in the 17th century marked the beginning of an era of profound transformation and tragic loss for the Ute. Initially, Spanish explorers and traders navigated the Ute territories, but it was the relentless westward expansion of the United States in the 19th century that truly reshaped the Ute world. Driven by the lure of gold, silver, and fertile agricultural lands, American settlers encroached upon Ute territories, leading to escalating conflicts.

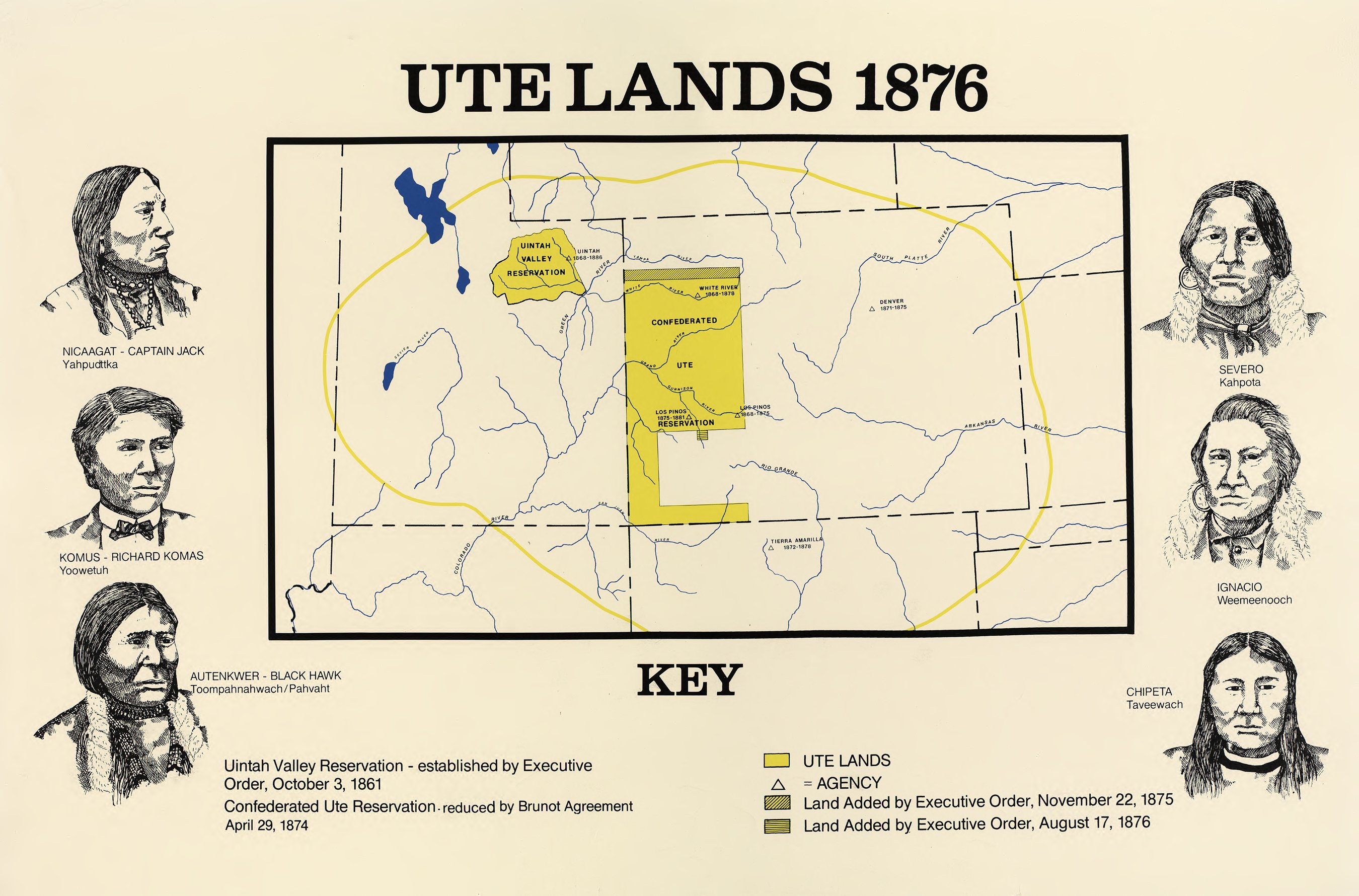

Between 1863 and 1880, a series of treaties were signed between the Ute and the U.S. government, each one progressively shrinking the Ute domain. The Treaty of 1868, for instance, established a reservation encompassing approximately 15.7 million acres in western Colorado, a significant reduction from their ancestral lands, but still a vast territory. However, even this agreement was short-lived. The discovery of gold in the San Juan Mountains, located within the new reservation, triggered a familiar pattern: miners flooded in, demanding access to the land.

This pressure culminated in the Ute Removal Act of 1880, which effectively dispossessed the U Ute of nearly all their remaining Colorado lands, forcing most to relocate to a new reservation in northeastern Utah. This act, a response to events like the Meeker Incident—a misunderstanding that escalated into violence—was a devastating blow, shattering their traditional way of life and severing deep cultural ties to specific places. By the early 20th century, the Ute, once masters of a vast domain spanning over 22 million acres, found their remaining land base reduced to scattered, often checkerboarded, reservations, totaling less than 1 million acres.

Today, three federally recognized Ute tribes carry forward this legacy: the Southern Ute Indian Tribe in Ignacio, Colorado; the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, primarily in Towaoc, Colorado, with lands extending into Utah and New Mexico; and the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in Fort Duchesne, Utah. Each tribe, while sharing a common heritage, has forged its own path, navigating the complexities of modern governance, economic development, and cultural preservation on their distinct land bases.

Sovereignty and Self-Determination: Building a Future

Despite the historical injustices, the Ute tribes have demonstrated remarkable resilience and a fierce commitment to self-determination. Central to this is the assertion of tribal sovereignty – the inherent right of tribes to govern themselves, manage their lands, and chart their own destinies. This principle, though often challenged by state and federal governments, forms the bedrock of their progress.

A prime example of this is the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, which has become a beacon of economic success among Native American nations. Leveraging their significant natural gas and oil reserves, the tribe established the Southern Ute Growth Fund in 2000. This highly diversified enterprise manages tribal assets and invests in a broad portfolio of businesses, both on and off the reservation, ranging from energy and real estate to telecommunications and private equity. The fund has generated substantial revenue, allowing the tribe to invest heavily in infrastructure, healthcare, education, and social services for its members.

"Our economic strength is a direct result of our ability to manage our own resources and make decisions that benefit our people," states a spokesperson for the Southern Ute. "It’s about self-sufficiency, ensuring that our children and grandchildren have opportunities that were denied to our ancestors."

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, situated amidst the dramatic landscapes of the Four Corners region, also actively manages its natural resources. They operate a modern casino and resort, a tribally owned farm and ranch, and engage in oil and gas production. Their focus on cultural preservation is equally strong, evident in the Weeminuche Construction Authority, which employs tribal members and works on projects that directly benefit the community, and the ongoing efforts to protect sacred sites like Bears Ears National Monument, a landscape rich with ancestral Ute history.

Further north, the Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation faces unique challenges and opportunities. Their reservation, one of the largest in the U.S. by area, is rich in energy resources, leading to significant oil and gas development. However, this also brings complex environmental considerations and jurisdictional disputes, particularly regarding "checkerboard" lands—parcels of tribal land interspersed with non-Indian owned land, creating legal and administrative headaches. The tribe has been at the forefront of landmark legal battles over water rights, crucial for both economic development and the sustenance of their communities in an arid region. The Ute Indian Tribe v. Utah case, for instance, affirmed the tribe’s jurisdiction over a significant portion of its reservation, a crucial victory for tribal sovereignty.

Cultural Resilience: Weaving Past into Future

Beyond economics and governance, the Ute tribes are fiercely dedicated to preserving their rich cultural heritage. Language revitalization programs are paramount, aiming to ensure the Ute language, a Shoshonean language, continues to be spoken by younger generations. Elders play a critical role in passing down traditional knowledge, stories, and ceremonies, such as the Sun Dance and the Bear Dance, which remain central to Ute spiritual life and community cohesion.

The land itself is an intrinsic part of this cultural preservation. Traditional ecological knowledge, honed over millennia, guides their land management practices. Protecting sacred sites, maintaining traditional hunting and gathering areas, and engaging in environmental stewardship are not just policy decisions; they are cultural imperatives, extensions of their identity.

"The land speaks to us, if we only listen," explains a cultural preservation officer with one of the tribes. "It tells us who we are, where we came from. Our ceremonies, our language, our stories—they all come from this ground. We cannot lose that connection, or we lose ourselves."

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite their successes, Ute tribal lands and communities face ongoing challenges. Socioeconomic disparities, including higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and health issues compared to national averages, persist. The legacy of historical trauma continues to impact community well-being. Environmental concerns related to resource extraction, coupled with the broader impacts of climate change, demand careful management and adaptation. Jurisdictional disputes with state and local governments over law enforcement, taxation, and land use are a constant reminder of the complex relationship between tribal nations and the surrounding society.

Yet, the Ute remain steadfast. Their vision for the future is one of continued self-sufficiency, cultural vibrancy, and responsible stewardship of their lands and resources. They are actively exploring renewable energy projects, developing tourism initiatives that share their culture respectfully, and investing in education and healthcare for their members. They are also increasingly asserting their voice in regional and national dialogues, advocating for tribal rights, environmental protection, and a more equitable future for all Indigenous peoples.

The story of Ute tribal lands is not merely a tale of past injustices; it is a living narrative of adaptation, perseverance, and unwavering connection. From the high mountain peaks to the red rock canyons, the echoes of the Nuche resonate, a testament to a people who, despite all odds, continue to thrive on the lands that have defined them for generations. Their journey reminds us that the true value of land lies not just in its resources, but in the identity, culture, and spirit it nurtures—a legacy that will endure for countless generations to come.