Wagon Bed Spring: The Prairie’s Enduring Oasis and a Testament to American Grit

The vast, undulating expanse of the Kansas prairie, stretching to horizons that seem to mock human scale, has long been a canvas for American dreams and the crucible of its enduring spirit. Within this immense landscape, amidst the whispering grasses and the relentless sun, lies a deceptively simple landmark: Wagon Bed Spring. More than just a trickle of water in the dust, this humble spring on the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail was a vital artery, a beacon of survival, and a silent witness to the triumphs, tragedies, and indomitable will of those who dared to venture west.

Today, marked by a stone monument and the quiet reverence of history enthusiasts, Wagon Bed Spring may appear unremarkable to the casual observer. But to understand its profound significance is to peel back layers of time, to hear the creak of ox-drawn wagons, the shouts of teamsters, the desperate gasps of the thirsty, and the wary silence of those who knew danger lurked just beyond the next rise. It is to grasp the sheer, brutal necessity of water in a land that offered little mercy.

The Great Artery West: The Santa Fe Trail

The Santa Fe Trail, forged in 1821 by the intrepid William Becknell, was America’s first international highway, a commercial artery that pulsed with the promise of trade and adventure. Stretching nearly 900 miles from Independence, Missouri, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, it connected the burgeoning United States with the ancient, exotic markets of the Southwest. But it was no easy road. Travelers faced blistering heat, freezing blizzards, treacherous rivers, and the ever-present threat of Native American encounters.

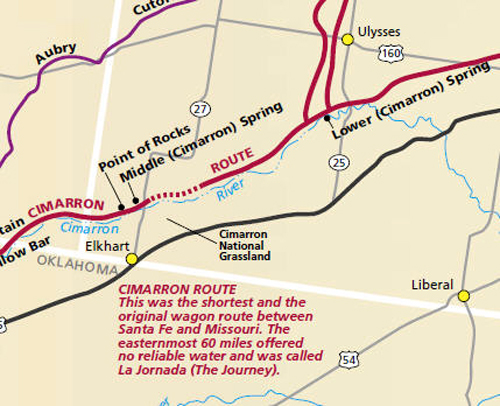

The trail branched into two main routes west of Dodge City, Kansas. The Mountain Route, while longer, offered more reliable water sources and timber. The Cimarron Cutoff, however, promised a shorter, flatter, and therefore faster journey – a crucial factor for traders eager to reach market. But this shortcut came at a steep price: a brutal 60-mile stretch, often referred to as the "Jornada del Muerto" (Journey of the Dead Man) by some, almost entirely devoid of reliable water. It was in the heart of this parched wilderness that Wagon Bed Spring became not just important, but utterly indispensable.

A Life-Giving Trickle: The Spring’s Unique Role

What made Wagon Bed Spring so unique was its dependable, albeit shallow, supply of water. Unlike ephemeral prairie puddles, this spring, fed by an underground aquifer, offered a constant source. Its name itself tells a story: pioneers often had to dig out a "bed" or depression, sometimes lining it with a wagon bed to prevent the sandy soil from collapsing, in order to collect enough water for themselves and their livestock.

"To see the faint shimmer of water after days of parched earth was to feel life itself surge back into weary bones," a sentiment often echoed by those who traversed the Cimarron Cutoff. For men, women, and animals pushed to the brink of endurance, the spring represented the difference between life and agonizing death. It was the last reliable water source for westbound travelers on the cutoff for many miles, and the first for those heading east. Its location was etched into the minds of every teamster, trader, and soldier who dared the Cimarron.

A Crossroads of Cultures and Conflict

The Cimarron Cutoff, and Wagon Bed Spring specifically, was not an empty wilderness. It was the ancestral hunting grounds of various Plains Indian tribes, particularly the Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who viewed the influx of American wagons as an invasion. These tribes depended on the vast buffalo herds that roamed the plains, and the Santa Fe Trail disrupted these herds and the tribes’ traditional way of life. This fundamental clash of cultures inevitably led to conflict.

Travelers along the trail were constantly on guard. Attacks by Native American warriors, often seeking horses, supplies, or simply to drive the intruders from their lands, were a constant danger. Wagon Bed Spring, being a critical stop, became a focal point for these encounters. It offered a respite, but also a vulnerable target.

One of the most notable conflicts occurred in August 1864, a grim year on the Santa Fe Trail. A detachment of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, under the command of Captain George H. Backus, was stationed at Wagon Bed Spring to protect supply trains and travelers. On August 8th, a large war party of Cheyenne warriors, numbering over 100, launched a surprise attack on Backus’s men.

The skirmish, often referred to as the Battle of Wagon Bed Spring, was fierce. The soldiers, though outnumbered, managed to defend their position, taking cover in the spring’s shallow banks and behind their wagons. They were eventually relieved by a column of troops, but not before suffering casualties. The battle underscored the perilous nature of the trail and the constant threat faced by those who dared to traverse it. It was a stark reminder that even at a life-giving oasis, death was often a close companion.

Beyond the Battles: Everyday Hardship

While battles captured headlines, the everyday grind of the trail exacted a heavy toll. Thirst was a constant companion. Josiah Gregg, a prominent trader and chronicler of the Santa Fe Trail, wrote extensively in "Commerce of the Prairies" about the suffering endured on the Cimarron Cutoff. His accounts, though perhaps not explicitly naming Wagon Bed Spring in every instance, vividly describe the desperate search for water: "The Cimarron route… was attended with greater risk and suffering, being almost entirely destitute of water." He recounts instances of men driven to madness by dehydration, of animals collapsing from exhaustion, and of the agonizing choices travelers had to make when water ran out.

The weather, too, was an unforgiving adversary. Blistering summer heat could send temperatures soaring, baking the earth and shriveling crops. Sudden, violent thunderstorms could turn dry arroyos into raging torrents, while winter blizzards could strand wagon trains for days, burying men and animals in snow and ice. Disease, from cholera to dysentery, spread rapidly through close-knit wagon trains, claiming lives with chilling efficiency. For every grand tale of adventure, there were countless stories of quiet suffering and resilience, of graves dug by the side of the trail, marked only by a simple cross or a pile of stones.

The Legacy Endures

As the 19th century drew to a close, the advent of the railroad gradually rendered the Santa Fe Trail obsolete. The iron horse, with its speed and capacity, replaced the lumbering ox-drawn wagons, and the need for remote oases like Wagon Bed Spring diminished. The ruts of the trail slowly faded into the prairie, swallowed by grass and time.

Yet, the legacy of Wagon Bed Spring endures. Today, it is recognized as a significant landmark on the Santa Fe National Historic Trail, managed by the National Park Service. Historical markers guide visitors to its location in Grant County, Kansas, inviting them to step back in time and contemplate the immense challenges faced by those who came before. The spring itself, still flowing though often a mere seep, continues its quiet work, a testament to the enduring power of nature and the timeless human need for sustenance.

Visiting Wagon Bed Spring today is a deeply contemplative experience. The silence is profound, broken only by the wind whispering through the prairie grasses, a sound that has remained unchanged for centuries. One can almost hear the echoes of the past: the distant lowing of cattle, the crack of a bullwhip, the desperate prayers for rain, the wary whispers of guards, and the grateful sighs of those who found life in its muddy waters.

The spring stands as a powerful symbol of American grit – the unyielding determination to overcome adversity, to push boundaries, and to forge a new path in the face of daunting challenges. It reminds us of the raw courage of pioneers, the fierce defense of ancestral lands by Native Americans, and the stark realities of survival on the frontier.

In a world increasingly defined by speed and convenience, Wagon Bed Spring serves as a vital anchor to our past, a tangible link to a time when every drop of water, every mile gained, and every sunrise was a hard-won victory. It reminds us that progress often comes at a cost, etched into the landscape and the very fabric of our national story, a story that continues to flow, like the enduring waters of this small, yet immensely significant, prairie oasis.