Wallace’s Whispers: Inside the Oasis Bordello Museum, A Time Capsule of Lives Unspoken

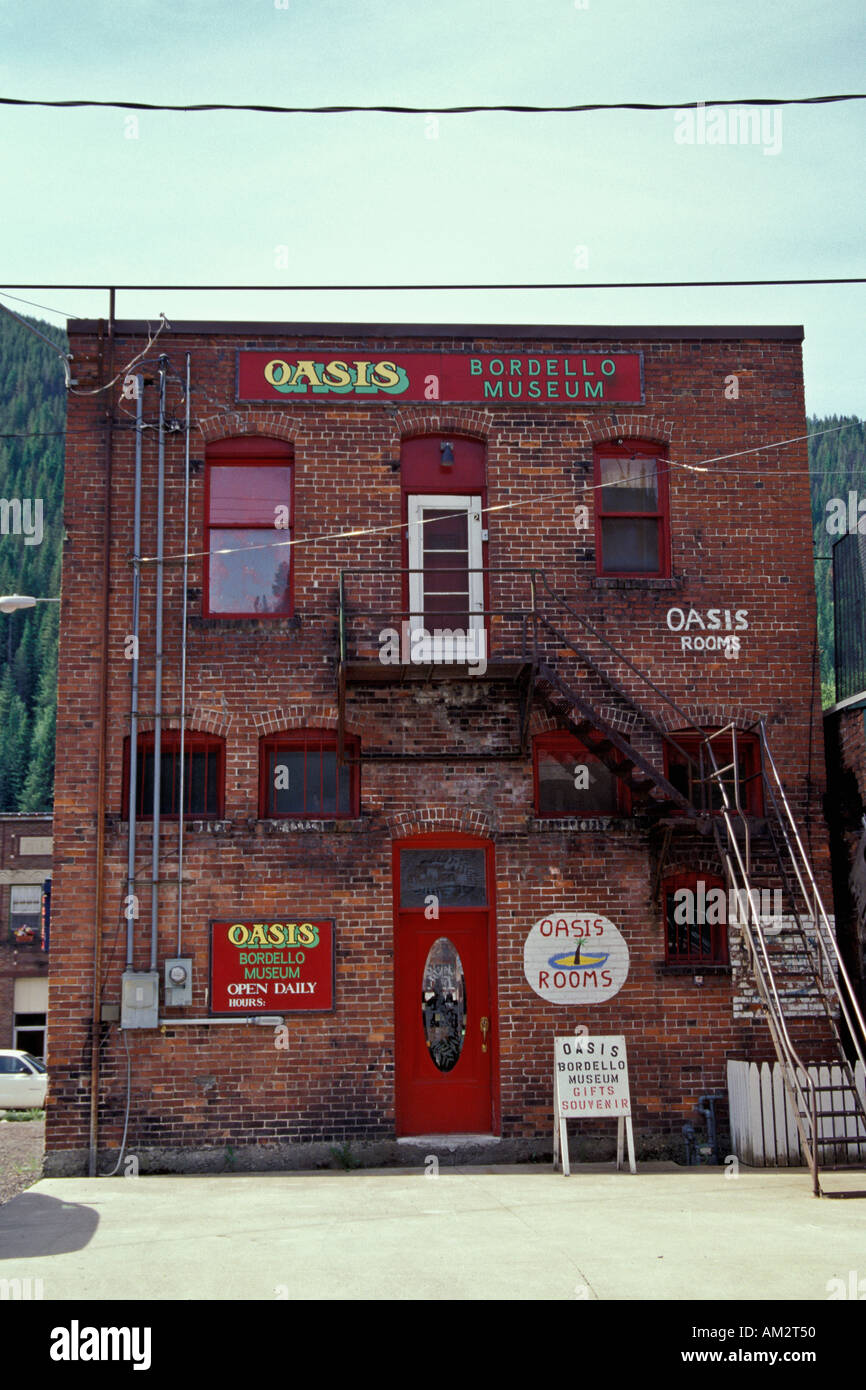

Wallace, Idaho. A town nestled deep within the Bitterroot Mountains, a place where the scent of pine and history hangs heavy in the air. It’s a town that proudly declares itself the "Center of the Universe," a tongue-in-cheek nod to its resilience and unique character. But beneath the surface of its quaint Victorian storefronts and a history etched in silver mining, Wallace holds a secret, a profound and poignant whisper from a bygone era: the Oasis Bordello Museum.

More than just a building, the Oasis is a perfectly preserved time capsule, a relic of a frontier past that refuses to be forgotten. Stepping inside its unassuming façade is like walking through a portal, not just to a different year, but to a different world. It’s a world of forbidden desires, economic necessity, and the complex lives of women who, for various reasons, found themselves entangled in the oldest profession. The museum doesn’t sensationalize or judge; it simply presents the stark, unvarnished reality of a segment of American history often relegated to hushed tones or sensationalized fiction.

The story of the Oasis, and indeed, many other bordellos in Wallace, is intrinsically linked to the town’s genesis. Founded in 1884 amidst the frenzy of the Coeur d’Alene mining boom, Wallace quickly became a bustling hub. Thousands of men flocked to the region, seeking their fortunes in silver, lead, and zinc. These were rough, isolated lives, often devoid of female companionship or the comforts of home. And where there is a large, transient male population with disposable income, there inevitably arises a demand for establishments like the Oasis.

For nearly a century, from its inception in the late 19th century until 1988, the Oasis operated openly, albeit sometimes with a wink and a nod, on Cedar Street. Prostitution, while technically illegal for much of its run, was often tolerated, even informally regulated, in boomtowns like Wallace. It was seen by some as a necessary evil, a pressure valve that kept the peace among a restless male workforce. The women who worked there were a recognized, if not always respected, part of the town’s social fabric. They frequented local shops, ate at the diners, and were, in many ways, an integral part of the local economy.

Then came the morning of February 12, 1988. Without warning, without a trace, the Oasis, along with Wallace’s other operating bordellos, simply closed. The women working there vanished, leaving behind their lives in astonishing detail. It was as if they had simply stepped out for a moment, perhaps for a lunch break or a quick errand, and never returned. The doors were locked, the lights turned off, and the passage of time inside was frozen.

For a decade, the building remained untouched, a silent sentinel on Cedar Street. Dust gathered, memories faded, and the whispers of its past grew fainter. Then, in 1998, new owners acquired the property. What they found inside was nothing short of extraordinary: a perfectly preserved tableau of lives suddenly interrupted.

"It was like a ghost ship, but on land," recounts a museum guide, her voice hushed as she walks visitors through the narrow hallways. "Everything was still here. Their clothes, their toiletries, even a half-eaten sandwich on a plate in the kitchen." This isn’t hyperbole. The museum’s rooms are filled with the personal effects of the women who lived and worked there: perfume bottles on dressers, hair curlers, cosmetics, magazines, records on a turntable, shoes neatly placed beside beds. A pair of reading glasses rests on a bedside table, a small notebook filled with numbers lies open. These aren’t staged props; they are the genuine articles, imbued with the lingering presence of their former owners.

The museum carefully preserves and displays these artifacts, offering a profound glimpse into the daily existence of the "working girls." There’s the main parlor, where clients would meet the women, a space adorned with velvet and ornate wallpaper, designed to project an air of sophistication. Beyond that are the "cribs" – smaller, more spartan rooms, each with a bed, a washbasin, and a minimal set of personal belongings. These were typically for the "crib girls," who worked on a faster, higher-volume basis. The "parlor girls," on the other hand, often had larger, more comfortable rooms, suggesting a higher status within the establishment and perhaps longer engagements with clients.

One of the most compelling aspects of the Oasis is its ability to humanize the women who worked there. They are often portrayed in popular culture as either tragic figures or glamorous vamps. The Oasis cuts through these stereotypes, revealing them as complex individuals. A closer look at the items left behind reveals snippets of their personalities: a romance novel, a self-help book, a photograph of a child, a worn deck of cards. These were women with hopes, dreams, sorrows, and daily routines, just like anyone else.

"We don’t glamorize it, and we don’t judge," explains Dave, a long-time resident and volunteer at the museum. "Our goal is to present the reality of their lives. For many of these women, this wasn’t a choice of luxury, but often a choice of survival. There were few opportunities for women in these mining towns, especially if they were single or without family support. This was a way to make a living, sometimes a better living than other options available to them at the time."

Indeed, historical accounts suggest that while the work was fraught with danger and social stigma, some women found a measure of independence and even financial security within the brothel system. They often earned significantly more than women working in other traditionally female roles like laundresses or domestic servants. Some saved money, bought property, or sent funds home to their families. The madam, who ran the establishment, often wielded considerable influence and managed a complex business operation.

The mystery of the sudden departure in 1988 continues to captivate visitors. Why did they leave so abruptly, abandoning their possessions and their livelihoods? While no definitive answer has ever emerged, speculation points to a confluence of factors: changing social attitudes, increased pressure from law enforcement (perhaps in response to a specific incident or a broader crackdown), or simply a quiet agreement to close down operations without drawing unwanted attention. The silence surrounding their departure is as profound as the silence that enveloped the building for a decade.

The Oasis Bordello Museum stands as a testament not only to the women who lived and worked there but also to Wallace’s unique place in American history. The entire town of Wallace is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a designation that ensures its architectural integrity and historical narrative are preserved. The museum adds another layer to this narrative, offering a vital, often overlooked, perspective on the social history of the American West. It challenges visitors to confront uncomfortable truths about gender, class, morality, and the economic forces that shaped the lives of individuals.

Walking through the Oasis, one can almost hear the faint echoes of laughter, the murmur of conversations, the clinking of glasses. The air, though still, seems to hold the ghosts of past lives, each object a silent witness to countless untold stories. It’s a powerful experience, prompting reflection on the complexities of history and the enduring human spirit.

The Oasis Bordello Museum is more than just a tourist attraction; it’s a profound educational experience. It forces us to reconsider our assumptions about the past, to look beyond the simplistic narratives, and to acknowledge the nuanced realities of lives lived on the fringes of society. It reminds us that history isn’t just about grand events and famous figures, but also about the everyday struggles and triumphs of ordinary people, especially those whose voices have long been silenced. In the quiet rooms of the Oasis, the whispers of those unspoken lives finally find an audience, ensuring that their stories, however unconventional, will never truly be forgotten.