Unearthing the Truth: The Wampanoag Perspective on Thanksgiving

PLYMOUTH, Massachusetts – For generations, the story has been etched into the American consciousness: a harmonious gathering in 1621, where Pilgrims, fresh off the Mayflower, shared a bountiful harvest feast with their Native American friends, the Wampanoag. It’s a foundational myth, painted with images of goodwill, shared prosperity, and the birth of a nation’s most cherished holiday. Yet, for the Wampanoag people themselves, the true narrative is far more complex, fraught with betrayal, loss, and a history that often remains untold.

The idyllic scene of cooperation, commonly depicted in school textbooks and holiday decorations, represents a carefully curated version of history, one that largely omits the devastating impact of colonial expansion on Indigenous communities. To truly understand the 1621 event, and the subsequent trajectory of Indigenous-settler relations, one must peel back the layers of myth and confront the uncomfortable truths beneath.

A World Before the Mayflower

Before the arrival of the English, the land now known as New England was a thriving, sophisticated landscape, meticulously managed by numerous Indigenous nations, including the Wampanoag. The Wampanoag, or "People of the First Light," had lived in the region for over 12,000 years. They were not primitive hunter-gatherers but a highly organized society with a complex political structure, advanced agricultural practices, extensive trade networks, and a deep understanding of their environment. Their diet consisted of corn, beans, squash, fish, shellfish, and wild game. They lived in settled villages, built sturdy homes, and maintained a rich cultural and spiritual life.

The village of Patuxet, where the Pilgrims would eventually establish Plymouth Colony, was once a vibrant Wampanoag community. But by the time the Mayflower arrived in 1620, Patuxet lay deserted, a haunting testament to a catastrophe that preceded the Pilgrims’ landing.

The Silent Killer: Disease

The most significant, yet often overlooked, factor shaping the initial interactions between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims was disease. European traders and explorers had been visiting the New England coast for decades prior to 1620, inadvertently introducing devastating Old World diseases like leptospirosis, smallpox, and measles against which Native populations had no immunity. From 1616 to 1619, a catastrophic epidemic – believed to be leptospirosis – swept through the region, decimating Indigenous communities. The Wampanoag population, estimated to be around 50,000 to 100,000 prior to contact, was reduced by as much as 90% in some areas. Patuxet was among the hardest hit.

This profound demographic collapse fundamentally altered the power dynamics. The Wampanoag Grand Sachem (paramount chief), Massasoit Ousamequin, found his confederation severely weakened, facing threats from rival Narragansett to the west, who had been less affected by the plague. It was this weakened state, not inherent friendliness, that drove Massasoit to seek an alliance with the newly arrived English.

The 1621 Event: A Strategic Alliance, Not a Friendly Invitation

The famous "First Thanksgiving" was not a spontaneous gesture of friendship but a direct outcome of a strategic political and military alliance forged in March 1621 between Massasoit and the Plymouth colonists. The Pilgrims, themselves ravaged by disease during their first winter (half of their original 102 passengers died), were in a precarious position. They needed help to survive in this unfamiliar land. Massasoit saw an opportunity to gain an ally against the Narragansett and access to European tools and weapons.

The feast itself, which occurred in the fall of 1621, was a harvest celebration by the Pilgrims. It was a three-day event. The Wampanoag were not "invited" in the modern sense. Instead, Massasoit and approximately 90 Wampanoag men appeared after hearing celebratory gunfire from the Pilgrim settlement, concerned about potential conflict. Seeing it was a feast, they joined, bringing five deer to contribute to the meal. The menu was likely very different from today’s turkey, stuffing, and cranberry sauce; it probably included wild fowl (ducks, geese, swans, but not necessarily turkey), venison, fish, shellfish, corn, beans, and squash.

"It was a diplomatic meeting, a practical arrangement for survival on both sides," explains Paula Peters, a Wampanoag historian and author. "It wasn’t about coming together in friendship and brotherhood. It was about Massasoit asserting his power and the Pilgrims needing to survive."

Tisquantum: The Complicated Interpreter

Central to the Pilgrim’s survival and the success of the initial alliance was Tisquantum, better known as Squanto. His story is far more complex and tragic than the simple "helpful Indian" narrative. Tisquantum was a Patuxet man who had been kidnapped by an English explorer, Thomas Hunt, in 1614 and sold into slavery in Spain. He eventually escaped, made his way to England, and learned English. He returned to his homeland in 1619 only to discover that his entire village, Patuxet, had been wiped out by the plague.

He found himself a man without a tribe, but with invaluable linguistic and cultural knowledge. Massasoit, recognizing his utility, effectively "assigned" him to the Pilgrims as an interpreter and guide. Tisquantum taught the Pilgrims how to cultivate native crops like corn, identify edible plants, and fish in the local waters. He was instrumental in mediating between the two groups, but his motivations were complex; he also leveraged his position for personal gain and influence, at times playing the Pilgrims and Massasoit against each other.

The Unraveling: From Alliance to Annihilation

The peace established in 1621, however, was short-lived. As more English settlers arrived, their demands for land and resources grew insatiable. The Pilgrims, driven by religious zeal and a belief in their divine right to the land, began to encroach on Wampanoag territory, dismantle their traditional way of life, and force conversions to Christianity. The initial alliance deteriorated into a pattern of escalating conflict.

Massasoit maintained the peace for over 40 years until his death in 1661. But his son, Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), recognized that the English expansion posed an existential threat to his people. By the 1670s, the Wampanoag and other Indigenous nations were pushed to the brink.

This escalating tension culminated in King Philip’s War (1675-1678), one of the bloodiest conflicts in American history. It was a brutal struggle for survival for the Indigenous people, and a fight for dominance for the colonists. The war resulted in the near-total destruction of the Wampanoag and their allies. Thousands of Native Americans were killed, enslaved, or forced to flee their ancestral lands. Many of those captured, including Metacom’s wife and son, were sold into slavery in the West Indies.

The end of King Philip’s War effectively marked the end of Indigenous sovereignty in southern New England. Ironically, some of the earliest "thanksgiving" proclamations by the colonists after 1621 were not about peaceful coexistence, but about celebrating military victories over Native Americans.

A Day of Mourning, Not Celebration

For many Wampanoag and other Indigenous peoples, Thanksgiving is not a day of celebration but a National Day of Mourning. This tradition began in 1970 when Frank James (Wamsutta), a Wampanoag leader, was invited to speak at a state dinner celebrating the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrim landing. When the organizers saw his prepared speech, which detailed the true history of betrayal and land theft, they forbade him from reading it. James refused to read an altered version and instead went to Cole’s Hill overlooking Plymouth Rock, where he delivered his powerful speech to a crowd of supporters.

"We, the Wampanoag, were the first to greet you, and it was our hands that helped you survive," James stated in his speech. "Yet, what we remember is not the feast, but the genocide, the theft of our lands, the destruction of our way of life. We are not celebrating Thanksgiving; we are mourning."

Since then, on every Thanksgiving Day, Indigenous people and their allies gather at Cole’s Hill for the National Day of Mourning, commemorating the genocide of their ancestors and the ongoing struggles of Native peoples worldwide. It is a day to reflect on the devastation wrought by colonization and to protest the racism and oppression that continue to plague Indigenous communities.

Reclaiming the Narrative

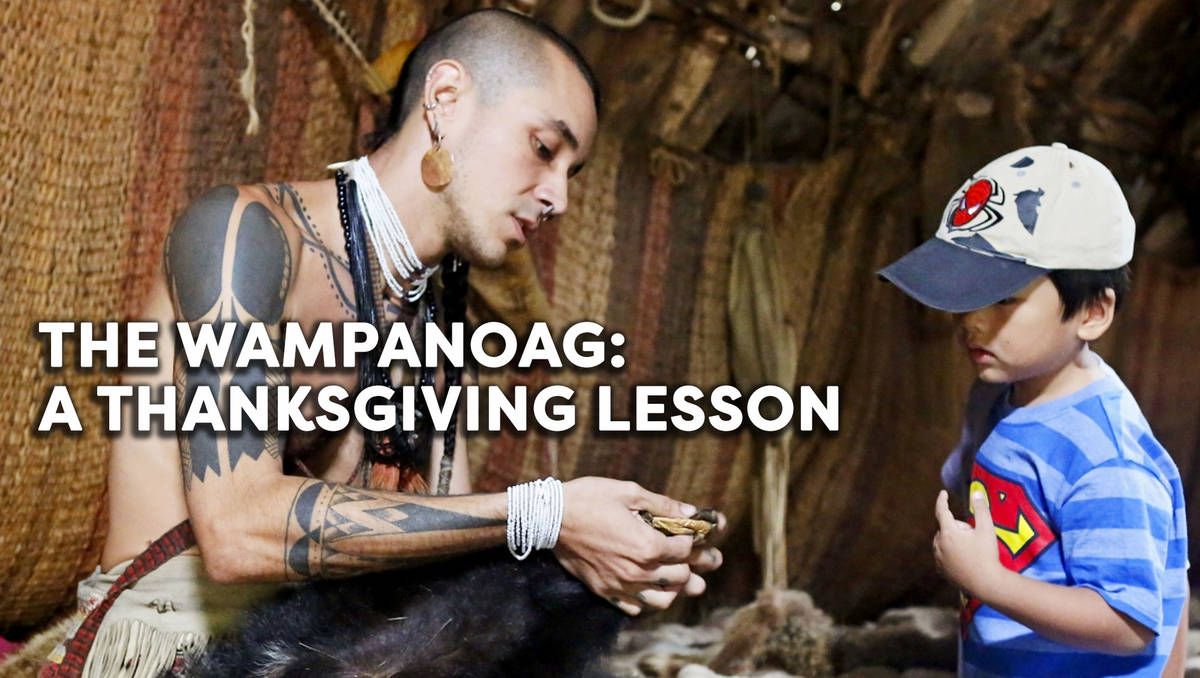

Understanding the true history of Thanksgiving is not about shaming or guilt-tripping, but about fostering a more accurate and inclusive understanding of America’s past. It’s about recognizing the resilience of Indigenous peoples and acknowledging the profound impact of historical events that continue to shape their lives today.

By embracing the Wampanoag perspective, we move beyond a simplistic myth to a richer, more nuanced, and ultimately more truthful narrative. It’s a narrative that acknowledges the complex humanity of all those involved, the strategic decisions made, the devastating consequences of disease and colonization, and the enduring strength of Indigenous cultures. As Americans gather around their tables, perhaps a moment of reflection on this deeper history, and the voices that have long been silenced, can transform the holiday from a mere feast into a genuine moment of historical reckoning and empathy. The truth, in all its complexity, is far more valuable than any comforting myth.