Okay, here is a 1200-word article in English, written in a journalistic style, about Native American loanwords in English.

Echoes in English: Unearthing Native American Loanwords

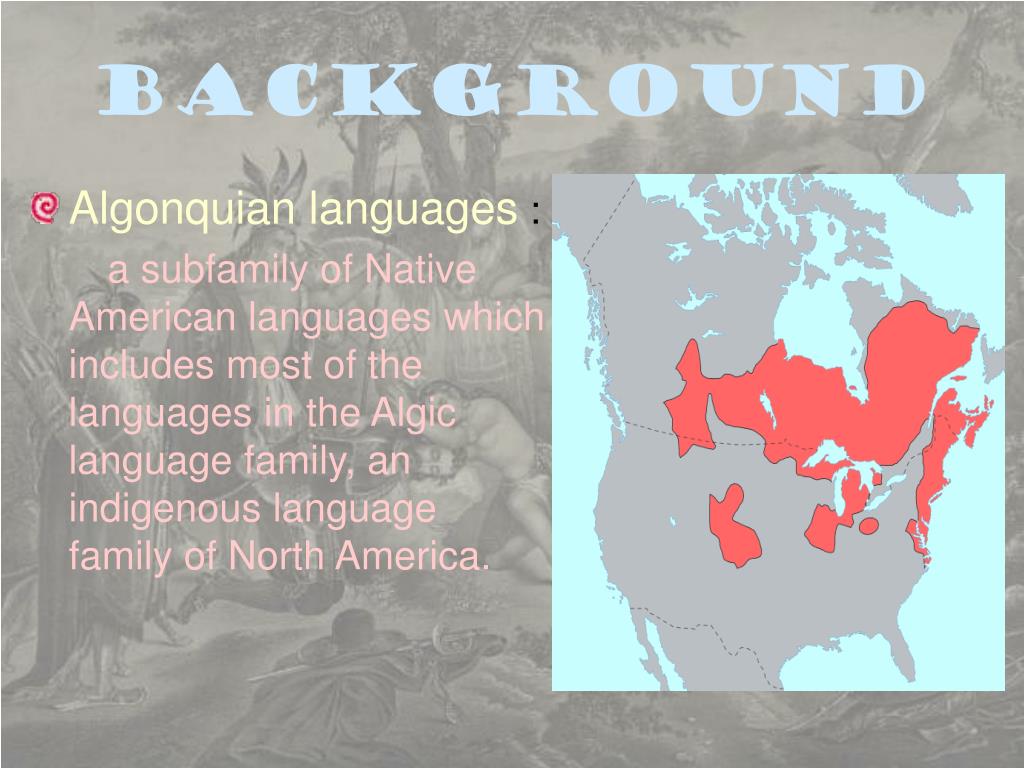

The English language, a vibrant tapestry woven from centuries of invasion, trade, and cultural exchange, often conceals its diverse origins within the mundane. We speak, write, and think in words whose journeys span continents and millennia, yet few realize how deeply some of our most common expressions are rooted in the very soil of the Americas. Beneath the surface of everyday conversation lies a fascinating linguistic layer: the enduring legacy of Native American loanwords.

These aren’t just obscure terms found in historical texts; many are words we use without a second thought, describing everything from the landscape we inhabit to the food we eat, the clothes we wear, and even the political processes we engage in. They are linguistic echoes of first encounters, indispensable tools for early European settlers to describe a new world, and silent testaments to the rich Indigenous cultures that shaped the continent long before the arrival of outsiders.

The Necessity of New Names

When European explorers and settlers arrived in North America, they encountered an utterly unfamiliar environment. The flora, fauna, geographical features, and social structures were unlike anything they had known in Europe. Faced with a continent teeming with new concepts and creatures, the existing English vocabulary proved woefully inadequate. Rather than inventing new words or attempting to force European labels onto American realities, settlers often adopted the terms already in use by the Indigenous peoples they encountered. This linguistic borrowing was a matter of practical necessity and cultural immersion.

"Language is a living thing, always borrowing, always adapting," notes Dr. Sarah Lingua, a historical linguist. "The sheer volume of new experiences for early settlers necessitated direct adoption of Indigenous terms. It was the most efficient way to communicate about their new surroundings."

This process was particularly evident in the naming of animals and plants unique to the Americas. Consider the humble skunk. Its distinctive odor and appearance were unknown in Europe, so the English borrowed the word from an Algonquian language (likely Massachusett or Narragansett), seganku or squnck, meaning "to urinate" or "to spray." Similarly, the agile raccoon comes from the Powhatan word arahkun, meaning "he scratches with his hands." The lumbering moose, a magnificent creature of the northern forests, derives its name from the Eastern Abenaki word moz.

Other iconic American animals that owe their names to Native American languages include the chipmunk (from an Ojibwe word ajidamoo, meaning "head-first tree climber"), the opossum (from Powhatan apasum, meaning "white animal"), and even the coyote (from the Nahuatl word coyōtl, though Nahuatl is a Mesoamerican language, its influence spread north).

From Forest to Farm: Food and Agriculture

Beyond the wild, Native American ingenuity in agriculture profoundly influenced the European diet and vocabulary. Many staple foods that are now global commodities were first cultivated by Indigenous peoples and introduced to the world via European contact, bringing their original names along.

The versatility of squash is legendary, and its name comes from an Algonquian word, askutasquash (Narragansett), meaning "green things eaten raw" or "something eaten raw or green." Over time, the word was shortened and Anglicized. Pecan, a delicious nut tree native to the southern United States, gets its name from the Algonquian word pakani, referring to a nut that requires a stone to crack.

Hominy, a dish made from dried maize kernels treated with an alkali, and succotash, a dish of maize and lima beans, are both contributions from Algonquian languages, specifically from Narragansett: homini from rockahominie (parched corn) and succotash from msickquatash (boiled corn kernels). These words reflect not just individual food items, but entire culinary practices adopted by the newcomers.

While many of the most famous food loanwords like tomato, chocolate, avocado, and chili hail from Nahuatl (the language of the Aztec Empire in Mesoamerica) rather than North American Indigenous languages, their widespread adoption often blends them into the broader category of "New World" linguistic contributions. Nevertheless, they underscore the profound impact Indigenous agricultural knowledge had on global cuisine and language.

Life and Culture: Tools, Dwellings, and Gatherings

The linguistic exchange wasn’t limited to the natural world and sustenance. Words describing tools, shelter, and social gatherings also found their way into English.

The canoe, an efficient and versatile watercraft, is a prime example. While various Indigenous groups had their own names for different types of boats, the word "canoe" entered English from the Taíno language of the Caribbean (canaoa), spreading north as the concept and craft were adopted. Similarly, the toboggan, a type of sled, and kayak, a type of small boat, are loanwords from Algonquian (specifically Mi’kmaq taba’gan) and Inuit languages respectively, reflecting the ingenious adaptations of northern peoples to their environments.

The traditional shelters of Native Americans also left their mark. Wigwam, a domed or conical dwelling, comes from an Algonquian word (wīkiwām in Ojibwe, wetu in Abenaki), meaning "their house." While often used generically, it specifically refers to the structures of Northeastern Indigenous peoples. The soft and comfortable moccasin, a type of shoe, is another Algonquian contribution (makasin in Powhatan or Ojibwe).

Perhaps one of the most widely recognized cultural loanwords is powwow. From the Narragansett word pauwau, meaning "spiritual leader" or "he dreams," it originally referred to a spiritual healing ceremony. Over time, its meaning in English broadened to encompass any gathering, particularly a large meeting or conference, though it still retains its association with Native American cultural events.

Politics and Place: Shaping the Map

Beyond daily life, Native American influence extends even into the realm of politics. The word caucus, a private meeting of a political party’s members to select candidates or decide policy, is believed to derive from an Algonquian word, possibly from the Massachusett caucauasu or kaukauas, meaning "adviser," "elder," or "one who advises." The Tammany Society, an influential political organization in 18th-century New York, was named after Tamanend, a revered Lenape chief, further cementing an Indigenous connection to American political discourse.

However, the most pervasive and undeniable linguistic legacy of Native Americans lies in the very names of the places we inhabit. A quick glance at a map of the United States reveals a mosaic of Indigenous names for states, cities, rivers, and mountains. These names are not mere labels; they are enduring monuments to the original inhabitants and their deep connection to the land.

-

States: At least half of the U.S. states bear names derived from Native American languages. Massachusetts (from Massachusett, meaning "at the great hill, place of"), Connecticut (from Mohegan-Pequot, meaning "on the long tidal river"), Ohio (from Seneca, meaning "great river"), Michigan (from Ojibwe, meaning "great lake"), Wisconsin (from Miami, meaning "river running through a red place"), Illinois (from Algonquian, referring to the Illiniwek people), Missouri (from Siouan, referring to the Missouria people), Dakota (from Dakota Sioux, meaning "friends" or "allies"), Iowa (from Ioway, meaning "sleepy ones"), Kansas (from Kansa, meaning "people of the south wind"), Nebraska (from Omaha-Ponca, meaning "flat water"), Oklahoma (from Choctaw, meaning "red people"), Wyoming (from Munsee Delaware, meaning "at the big river flat"), and Alaska (from Aleut, meaning "great land" or "mainland").

-

Cities and Rivers: The list is virtually endless. Chicago (from Miami-Illinois, meaning "wild garlic place"), Seattle (named after Chief Si’ahl of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes), Milwaukee (from Algonquian, meaning "good land" or "gathering place by the water"), Mississippi (from Ojibwe, meaning "great river"), Potomac (from Algonquian, meaning "where the tribute is brought"), Chattanooga (from Creek, meaning "rock that comes to a point"), and Spokane (from the Spokane tribe, meaning "children of the sun").

"The names on our maps are not just geographical markers; they are testaments to the original inhabitants and their profound understanding of the land," says Dr. Lingua. "They are a constant, albeit often unnoticed, reminder of the layers of history beneath our feet."

The Ongoing Journey of Words

The process of linguistic borrowing is rarely a static one. Over centuries, Native American loanwords have been Anglicized, their spellings and pronunciations adapting to English phonetic rules. The "opossum" became "possum," "askutasquash" became "squash," and the original sounds often softened or simplified. This assimilation process sometimes obscures their Indigenous origins, making them seem indistinguishable from words of Germanic or Latin roots.

Yet, despite this linguistic transformation, their presence in English is a powerful reminder of the deep and often overlooked contributions of Native American cultures. They represent more than just individual words; they embody a history of interaction, adaptation, and the invaluable knowledge shared by the continent’s first peoples.

In an increasingly globalized world, where languages constantly intertwine, the story of Native American loanwords in English serves as a poignant example of linguistic resilience and cultural exchange. They are not merely museum pieces of language but living threads in the fabric of our everyday communication, inviting us to reflect on the rich heritage that continues to shape our identity as Americans, one word at a time. The next time you enjoy a bowl of succotash, put on your moccasins, or simply look at a map, remember the echoes of the original voices that helped name this land and its wonders.