Echoes of the Plains: Unveiling the Enduring Tapestry of Lakota Traditions

In the vast expanse of the North American Great Plains, where the wind whispers tales through tall grasses and the horizon stretches limitlessly, resides a people whose spiritual and cultural roots run as deep as the rivers that carve the land. They are the Lakota, a prominent division of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), often known as the Sioux. Far from being relics of a bygone era, Lakota traditions are a vibrant, living force, a testament to resilience, profound spirituality, and an unbreakable connection to the natural world.

To understand Lakota traditions is to step into a worldview where everything is interconnected – human, animal, plant, and spirit. It is a philosophy rooted in reciprocity, respect, and a deep reverence for Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery or Great Spirit, who permeates all existence. This isn’t merely a set of customs; it is a way of life, a framework for understanding one’s place in the universe and one’s responsibilities to community and creation.

The Spiritual Core: Wakan Tanka and Mitakuye Oyasin

At the heart of Lakota spirituality lies the concept of Wakan Tanka. This is not a single deity in the Abrahamic sense, but rather a collective term for all sacred powers and mysteries, encompassing the four directions, the sky, the earth, and the various spirits of animals and natural phenomena. Every aspect of life, from the rising sun to the smallest insect, is imbued with sacredness.

This profound understanding of interconnectedness is encapsulated in the well-known Lakota phrase, "Mitakuye Oyasin" – "All My Relations." It is a recognition that all beings are related, part of the same vast family, and thus deserve respect and compassion. This isn’t just a greeting; it’s a foundational principle that guides interactions, ceremonies, and daily life. It implies a responsibility to care for the earth, for fellow humans, and for all living things, as they are all part of one’s extended family.

The genesis of many Lakota sacred practices is attributed to the miraculous appearance of the White Buffalo Calf Woman. As the story goes, she brought the Chanunpa, the Sacred Pipe, to the Lakota people, along with instructions for its use and the seven sacred rites that form the bedrock of their spiritual life. The pipe is not merely a tool for smoking; it is a profound instrument of prayer, a conduit between the human and spirit worlds. Its smoke carries prayers to Wakan Tanka, and its bowl represents the heart, while the stem represents the path to truth.

The Seven Sacred Rites: Pathways to Understanding

The seven sacred rites, gifted by the White Buffalo Calf Woman, are the pillars of Lakota spiritual practice, each serving a unique purpose in purification, prayer, healing, and connection. While often adapted to modern contexts, their core meanings remain steadfast:

-

Inipi (Sweat Lodge Ceremony): Perhaps the most widely practiced Lakota ceremony today, the Inipi is a powerful rite of purification and renewal. Participants enter a dome-shaped lodge, often covered with blankets or tarps, where water is poured over heated stones in the center, creating intense steam. This dark, hot, womb-like environment symbolizes a return to the earth, cleansing the body, mind, and spirit. Prayers are offered for self, family, community, and all of creation, fostering humility and connection.

-

Hanblecheya (Vision Quest): A deeply personal and profound journey, the Vision Quest involves an individual isolating themselves in a remote, sacred location, often for several days without food or water. The purpose is to seek guidance, a vision, or a spiritual helper from Wakan Tanka. It is a test of endurance, a stripping away of worldly concerns to open oneself to spiritual insight. Successful questers return with clarity, purpose, and often a new name or song.

-

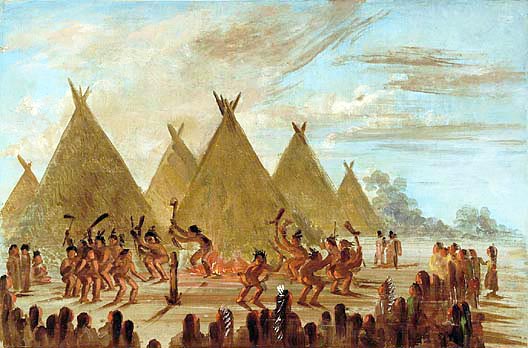

Wi-wanyang-wacipi (Sun Dance): The most sacred and arduous of Lakota ceremonies, the Sun Dance is an annual ritual of sacrifice, prayer, and renewal for the entire community. Held during the summer solstice, it involves several days of fasting, dancing, and prayer around a central sacred tree (the Cottonwood Tree, representing the Tree of Life). For some participants, a central element involves voluntary piercing of the chest or back, with rawhide thongs attached to the sacred tree. This physical sacrifice is a deeply personal offering to Wakan Tanka for the well-being of the community, for healing, or in fulfillment of a vow. As one elder might say, "It is a time for renewal, for giving back to the Creator what has been given to us, for the strength of our people." It embodies the Lakota values of courage, generosity, and community responsibility.

-

Hunkapi (Making of Relatives Ceremony): This ceremony creates a sacred bond, akin to adoption, between two individuals or families. It establishes a spiritual kinship that transcends blood ties, solidifying alliances and extending the concept of "Mitakuye Oyasin" to non-relatives, fostering unity and mutual support.

-

Isnati Awicalowanpi (Female Puberty Rite): This rite celebrates a young woman’s transition into adulthood and womanhood. It acknowledges her sacred power and her potential to bring forth life, emphasizing her importance to the family and community.

-

Wiwanyank Wacipi (Ghost Keeping Ceremony): This complex ceremony is performed to release the spirit of a deceased loved one, typically after a year of mourning. The spirit is "kept" in a sacred bundle, and through rituals and prayers, is finally released to the spirit world, allowing both the spirit and the grieving family to find peace.

-

Yuwipi (Healing Ceremony): A private, nighttime healing ritual conducted by a specially trained spiritual leader (Yuwipi man or woman). The leader is bound and placed in a darkened room, where spirits are invited to assist in healing, divination, or guidance for those present.

Social Fabric and Core Values

Beyond the grand ceremonies, Lakota traditions are woven into the very fabric of daily life and social structure. The Tiyospaye, the extended family unit, is the cornerstone of Lakota society. It encompasses not just immediate family but also aunts, uncles, cousins, and adopted relatives, functioning as a primary unit of support, education, and cultural transmission. Decisions are often made communally, reflecting the emphasis on harmony and collective well-being over individual ambition.

Traditional Lakota values are deeply ingrained and universally taught:

- Woohitika (Bravery/Courage): Not just in battle, but in facing challenges, speaking truth, and upholding principles.

- Woahwala (Humility/Respect): Respect for elders, for children, for women, for the land, and for all living things.

- Woksape (Wisdom): Acquired through experience, listening, and spiritual insight, often embodied by elders.

- Wowacintanka (Fortitude/Generosity): The ability to endure hardship and the willingness to give freely to others, even when one has little. Status was often gained not by accumulating wealth, but by giving it away in "giveaways."

The buffalo, or Tatanka, was central to Lakota life. It provided food, shelter (tipis from hides), clothing, tools, and spiritual sustenance. The Lakota’s nomadic lifestyle was intrinsically linked to the buffalo’s migratory patterns. The decimation of the buffalo herds by European settlers in the 19th century was not just an economic disaster but a profound spiritual and cultural wound, disrupting a way of life that had thrived for centuries.

Resilience and Revival in the Modern Era

The history of the Lakota people post-European contact is one of immense challenge, marked by broken treaties, forced removals, assimilation policies, and tragic events like the Wounded Knee Massacre. Yet, despite these adversities, Lakota traditions have not only survived but are experiencing a powerful revival.

Today, Lakota people are actively engaged in preserving and revitalizing their heritage. Language immersion programs are teaching Lakota to new generations, recognizing that language is a carrier of culture and worldview. Cultural centers, museums, and educational initiatives are sharing traditional knowledge, arts (like beadwork, quillwork, and hide painting), and storytelling with both tribal members and the wider world. Powwows, while often incorporating intertribal elements, remain important venues for celebrating Lakota identity through dance, song, and regalia.

Young Lakota people are increasingly embracing their ancestral practices, finding strength and identity in ceremonies like the Inipi and participating in Sun Dances. This resurgence is not a romanticized return to the past, but a dynamic adaptation of ancient wisdom to contemporary challenges, addressing issues like historical trauma, economic disparities, and environmental stewardship.

As LaDonna Brave Bull Allard (Standing Rock Sioux) once said, "Our spirituality is our resistance." For the Lakota, traditions are not merely historical artifacts; they are living pathways to healing, sovereignty, and a sustainable future. They offer profound lessons in humility, interconnectedness, and resilience that resonate far beyond the plains, providing a vital perspective for all who seek a deeper understanding of humanity’s place in the intricate web of life.

In a world increasingly disconnected from nature and community, the enduring traditions of the Lakota people stand as a powerful reminder of what it means to live in harmony with the earth and with one another, guided by the timeless wisdom of "Mitakuye Oyasin." They are indeed echoes of the plains, reverberating with profound meaning for generations to come.