Guardians of the Earth: The Enduring Power of Native American Environmental Movements

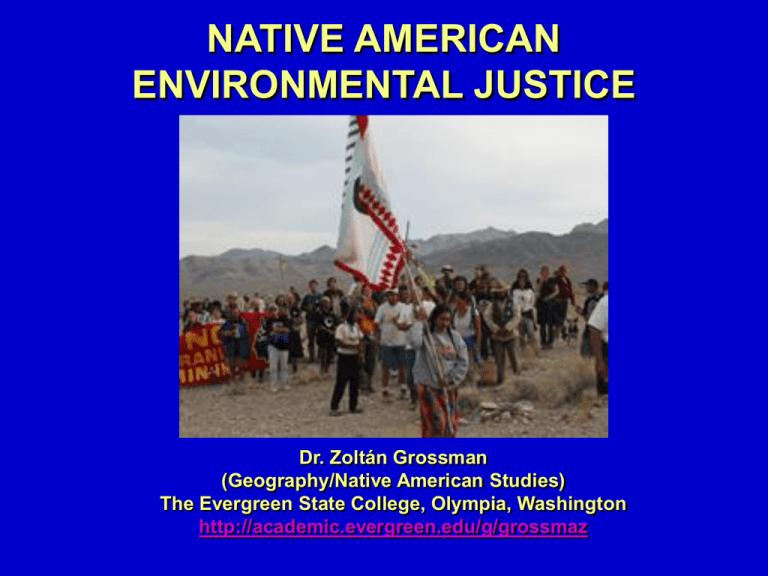

The biting winds of the North Dakota plains carried not just the chill of winter but also the resolute chants of "Mni Wiconi – Water is Life." For months in 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation became a crucible, a global focal point where thousands of Indigenous people and their allies converged to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). This wasn’t merely a protest; it was a profound spiritual and environmental stand, a modern manifestation of a centuries-old struggle that defines Native American environmental movements.

Far from being a recent phenomenon, Native American environmental activism is deeply rooted in ancient philosophies, traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), and an inherent understanding of humanity’s interconnectedness with the natural world. It is a movement born of stewardship, survival, and sovereignty, a continuous fight against the forces that seek to exploit the land and its resources without regard for its sacred essence or future generations.

A Sacred Trust: The Philosophy of Stewardship

To understand Native American environmental movements, one must first grasp the foundational worldview that underpins them. For most Indigenous cultures, land is not merely property or a commodity to be exploited; it is a living entity, a relative, the source of life, culture, and spiritual identity. This perspective stands in stark contrast to the dominant Western paradigm, which often views nature as separate from humanity, a resource to be managed and extracted for economic gain.

"We are part of the Earth, and the Earth is part of us," famously stated Chief Seattle of the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes, encapsulating a philosophy of profound reciprocity. This worldview fosters a deep respect for all living things and a responsibility to maintain balance and harmony. A core principle is that of the "Seventh Generation," which posits that decisions made today should consider their impact seven generations into the future, ensuring the sustainability of resources and culture for descendants. This long-term vision naturally leads to a conservation ethic far predating modern environmentalism.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) is another cornerstone. Passed down through oral histories, ceremonies, and practical experience, TEK encompasses a vast body of knowledge about local ecosystems, plant and animal behaviors, sustainable harvesting practices, and climate patterns. It’s a dynamic, evolving system of understanding that has allowed Indigenous communities to thrive in diverse environments for millennia. When Indigenous communities protect their land, they are simultaneously protecting this invaluable knowledge, which holds keys to sustainable living for all humanity.

The Genesis of Resistance: Colonialism and Resource Exploitation

The arrival of European colonizers fundamentally disrupted this symbiotic relationship. The history of the United States is replete with examples of land dispossession, forced removals, and the imposition of a resource-extractive economy that disregarded Indigenous land tenure and spiritual ties. The California Gold Rush, the systematic destruction of buffalo herds, the clear-cutting of forests, and the damming of sacred rivers all represent early environmental disasters directly linked to the colonization of Native lands.

As Native peoples were confined to reservations, often on lands deemed undesirable by settlers, they found themselves disproportionately impacted by industrial pollution, mining operations, and resource extraction projects. Uranium mines on Navajo lands led to devastating health consequences, coal-fired power plants on tribal borders polluted the air, and pipelines crisscrossed sacred ancestral territories. These historical injustices laid the groundwork for modern environmental activism, as communities fought not just for their physical survival but for the survival of their cultural and spiritual heritage tied to the land.

The Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s, which championed Indigenous self-determination and treaty rights, provided a crucial foundation for the environmental movement. Organizations like the American Indian Movement (AIM) began to incorporate environmental concerns into their broader advocacy for sovereignty and justice, recognizing that control over land and resources was inextricably linked to tribal nationhood.

Key Battles and Modern Manifestations

In recent decades, Native American environmental movements have gained increasing prominence, drawing global attention to their struggles and offering alternative pathways to sustainability.

1. Water Protection (Mni Wiconi): Standing Rock and Beyond

The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) became a watershed moment. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, joined by hundreds of other tribes and thousands of non-Indigenous allies, opposed the pipeline’s route beneath Lake Oahe, a sacred site and the tribe’s primary source of drinking water. The protests highlighted the disproportionate burden placed on Indigenous communities and galvanized a broad environmental justice movement. LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a leader of the Sacred Stone Camp, articulated the core belief: "Water is life. We are here to protect the water for the children, for the animals, for the trees." While the pipeline was eventually completed, the movement forced a national conversation about Indigenous rights, environmental racism, and fossil fuel infrastructure.

Beyond DAPL, battles over water rights continue across the continent. The Ojibwe people of Minnesota have been at the forefront of the fight against Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline, which threatens the headwaters of the Mississippi River and vital wild rice beds, a traditional food source. In the Southwest, tribes continually fight for their rightful share of diminishing water resources amidst drought and agricultural demands.

2. Sacred Sites and Land Protection:

Many environmental battles are fundamentally about the protection of sacred sites. Oak Flat (Chi’chil Bildagoteel) in Arizona, a traditional Apache holy ground, is threatened by a proposed copper mine. The Lakota people continue their struggle to protect the Black Hills (Paha Sapa) in South Dakota, a sacred landscape and the site of the Mount Rushmore monument. These fights underscore that for Indigenous peoples, land is not just an ecosystem but a living spiritual landscape woven into their identity, ceremonies, and oral histories.

3. Climate Justice:

Native American communities are often on the front lines of climate change, experiencing its impacts more acutely due to their reliance on traditional lands and subsistence practices. Coastal tribes face displacement from rising sea levels, Arctic communities contend with melting permafrost and disappearing ice, and Southwestern tribes grapple with extreme drought. Recognizing this vulnerability, Indigenous leaders have become powerful voices in the global climate justice movement, advocating for systemic change, a just transition away from fossil fuels, and the inclusion of TEK in climate solutions. Winona LaDuke, an Anishinaabemong environmental activist and founder of Honor the Earth, famously stated, "Indigenous people have been disproportionately affected by climate change and are leading the way in finding solutions."

4. Challenging Extraction and Pollution:

From uranium mining on the Navajo Nation to oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) – sacred to the Gwich’in people – Native American communities have consistently resisted extractive industries that pollute their lands, water, and air. They highlight the legacy of environmental racism, where polluting industries are disproportionately sited near marginalized communities, including tribal lands.

Strategies and Impact:

Native American environmental movements employ a diverse range of strategies:

- Direct Action and Civil Disobedience: As seen at Standing Rock, peaceful protest and occupation of contested sites are powerful tools for raising awareness and disrupting projects.

- Legal Challenges: Tribes frequently pursue litigation in federal courts, invoking treaty rights, environmental laws, and tribal sovereignty to protect their lands and resources. The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) and similar organizations play a crucial role in these legal battles.

- International Advocacy: Indigenous leaders regularly bring their concerns to international forums like the United Nations, highlighting human rights abuses and the global implications of environmental destruction on their lands.

- Education and Awareness: Through storytelling, media engagement, and community organizing, these movements educate the public about Indigenous perspectives on environmentalism and the interconnectedness of land, culture, and health.

- Building Alliances: Native American environmental movements have forged powerful alliances with non-Indigenous environmental groups, human rights organizations, and faith-based communities, amplifying their message and increasing their collective power.

The impact of these movements extends beyond individual victories against specific projects. They have fundamentally shifted the discourse around environmentalism, emphasizing social justice, Indigenous rights, and the value of TEK. They have also inspired a new generation of activists and brought greater visibility to the ongoing struggles of Native peoples. The appointment of Deb Haaland, a Laguna Pueblo woman, as the Secretary of the Interior marks a historic moment, placing an Indigenous leader at the helm of the federal agency responsible for managing much of the nation’s lands and natural resources.

The Path Forward: Resilience and Hope

Despite immense challenges – underfunding, continued pressure from powerful industries, and a persistent lack of understanding from mainstream society – Native American environmental movements remain resilient. Their fight is not just for themselves but for the health of the entire planet. As guardians of biodiversity, protectors of sacred sites, and holders of invaluable ecological knowledge, Indigenous peoples offer profound lessons in sustainable living and a powerful vision for a future where humanity lives in harmony with the Earth.

Their enduring message is a universal call to action: to recognize the sacredness of the land, to understand our place within the web of life, and to make decisions with the well-being of the Seventh Generation in mind. In a world grappling with climate crisis and ecological degradation, listening to and supporting Native American environmental movements is not just an act of justice, but a critical step towards planetary survival. Their legacy of resistance and stewardship offers a beacon of hope for a more balanced and sustainable future for all.