The Invisible Nations: Understanding Non-Federally Recognized Tribes in the U.S.

In the vast tapestry of the United States, a narrative often told is one of diversity and self-determination. Yet, beneath the surface of commonly understood American history lies a complex and often heartbreaking truth for hundreds of Indigenous communities: they are tribes, with long histories, distinct cultures, and vibrant identities, but they are not federally recognized by the U.S. government.

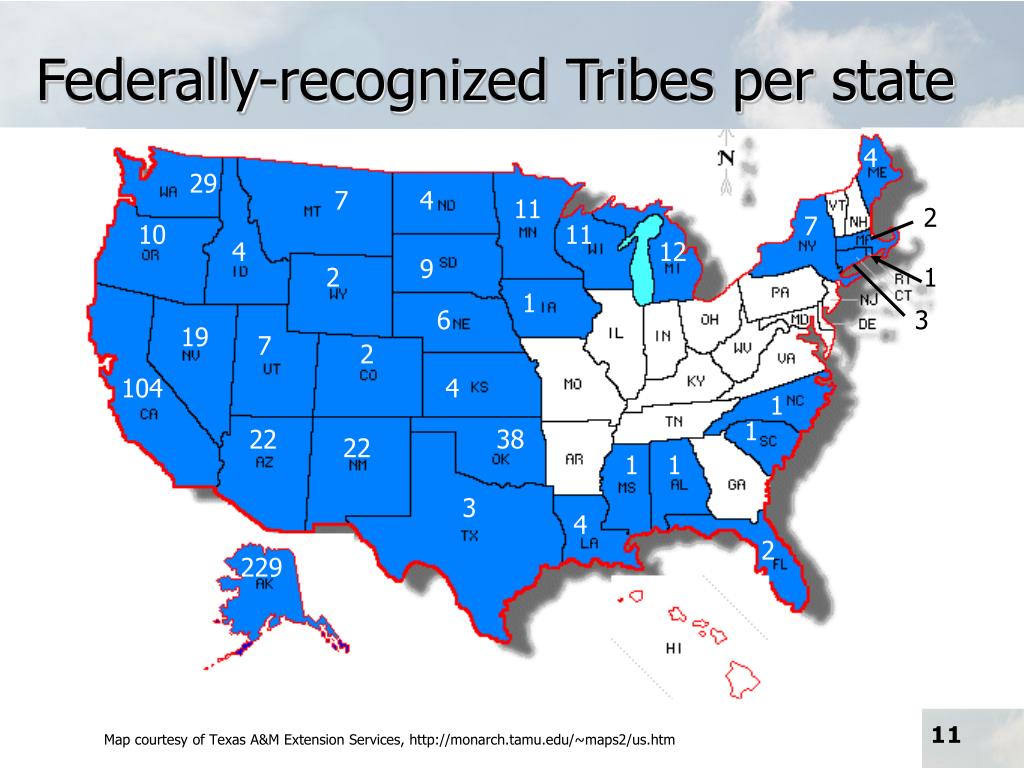

While the U.S. government officially recognizes 574 Native American tribes, each with a government-to-government relationship with Washington D.C., an estimated 400 additional tribes and Indigenous communities exist across the country, unrecognized by the federal system. These "invisible nations" navigate a unique and arduous path, fighting for their heritage, their rights, and their very existence in a system that often fails to acknowledge their inherent sovereignty.

What Does "Non-Federally Recognized" Mean?

To be clear, a "non-federally recognized tribe" is not a group that simply claims to be a tribe. These are communities that have maintained their cultural practices, social structures, familial ties, and historical narratives, often for centuries, despite immense pressure to assimilate or disappear. The distinction lies in their legal status with the U.S. government.

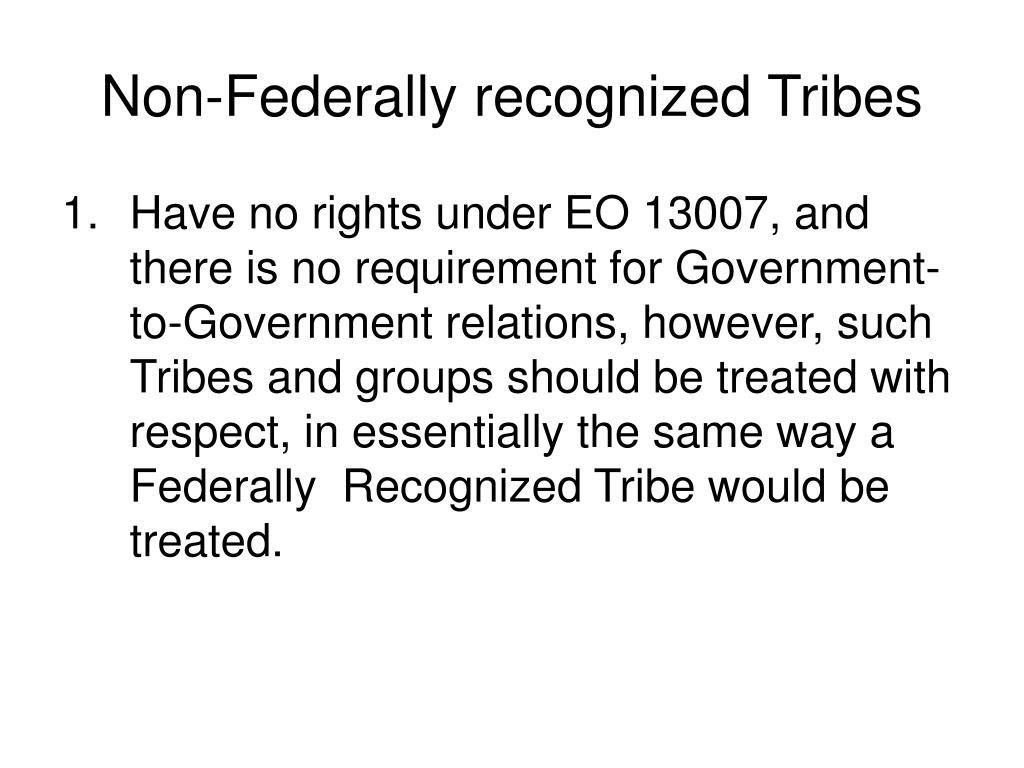

Federal recognition is a formal acknowledgment by the Department of the Interior that a tribe exists as a sovereign nation with a government-to-government relationship with the United States. This status confers a wide array of benefits and protections, including:

- Access to federal services: Healthcare (Indian Health Service), education (Bureau of Indian Education), housing, and social welfare programs.

- Land rights: Ability to place land into federal trust, protecting it from state taxation and development, and allowing for self-governance over their territory.

- Cultural and religious protections: Enhanced protections for sacred sites and repatriation of ancestral remains and cultural items under laws like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

- Economic development opportunities: Eligibility for federal grants, loans, and the ability to operate gaming enterprises under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA).

- Legal standing: The ability to assert sovereign rights in federal courts and engage in government-to-government negotiations.

For non-federally recognized tribes, these doors remain largely closed. They exist in a legal limbo, often unable to access the resources necessary to preserve their culture, develop their economies, or even adequately care for their elders and children.

A Legacy of Erasure: How Did This Happen?

The reasons for a tribe’s non-federal status are complex and rooted deeply in American history. They often stem from a combination of historical injustices, bureaucratic hurdles, and the very policies designed to "deal with" Indigenous populations.

- Termination Era (1940s-1960s): During this period, the U.S. government actively sought to end its relationship with Native American tribes, believing it would integrate Indigenous peoples into mainstream American society. Over 100 tribes were "terminated," meaning their federal recognition was revoked, their lands sold off, and their services cut. While some later regained recognition, many did not, leaving communities fractured and economically devastated.

- Lack of Treaties or Early Documentation: Many tribes, particularly those in the Eastern and Southern U.S., never signed treaties with the federal government. Their interactions were often with individual states, or they were simply overlooked during the westward expansion and land grabs. Without early federal documentation, proving their continuous existence and political authority to the satisfaction of modern bureaucratic standards becomes incredibly difficult.

- Genocide and Displacement: Violent conflicts, forced removals, and the deliberate destruction of cultural practices made it nearly impossible for some groups to maintain the kind of structured political organization that modern recognition processes demand. Generations of displacement and the need to hide their identity to survive led to gaps in documentation.

- The "Paper Genocide": Critics argue that the federal recognition process itself, administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), amounts to a form of "paper genocide." The criteria are incredibly stringent, requiring a tribe to prove continuous existence as a distinct community, a history of political authority, and descent from a historical tribe, all through voluminous historical and genealogical records. Many tribes, especially those whose records were lost due to forced removal, assimilation policies, or poverty, simply cannot meet these demands.

"It’s a process designed to fail," says Dr. David Wilkins, a prominent scholar of Native American politics, in his writings on federal recognition. "The burden of proof is astronomical, the costs are prohibitive, and the timeframes are measured in decades, not years." Indeed, a single petition for federal recognition can cost millions of dollars in research, legal fees, and administrative expenses, and can take 20, 30, or even 40 years to resolve. Many tribes simply run out of resources or generations pass before a decision is made.

The Staggering Consequences

The impact of non-federal recognition reverberates through every aspect of a community’s life:

- Healthcare Disparities: Without access to the Indian Health Service (IHS), members of non-recognized tribes often rely on underfunded state or local services, or have no healthcare at all. This contributes to higher rates of chronic disease and lower life expectancies.

- Educational Barriers: Lack of access to BIA schools or federal tribal education programs limits opportunities for their youth, perpetuating cycles of poverty.

- Economic Hardship: Without land in trust or the ability to engage in gaming, economic development options are severely limited. Businesses struggle to secure funding, and unemployment rates are often sky-high.

- Cultural Erosion: Without legal protections, sacred sites can be destroyed by development, and ancestral remains may not be repatriated. The fight for survival often overshadows efforts to revitalize languages and traditions.

- Identity Crisis and Mental Health: The constant struggle for recognition can take a severe toll on the mental health of community members. "It’s like constantly having to prove your humanity, your very existence, to a government that should already know who you are," a tribal elder from a non-recognized community once lamented in a community meeting. This constant invalidation can lead to profound feelings of marginalization and disenfranchisement.

A poignant example is the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, one of the largest Indigenous groups east of the Mississippi River. Despite having a continuous history, a thriving community of over 55,000 members, and a strong cultural identity, the Lumbee have been fighting for full federal recognition for over a century. They received limited recognition in 1956, but this act explicitly denied them federal benefits, making them a unique case of partial recognition without the accompanying rights. Their story highlights the arbitrary and often politically motivated nature of the recognition process.

Paths Forward: Resilience and Alternative Recognition

Despite the immense challenges, non-federally recognized tribes are far from passive. They are actively engaged in various strategies to assert their sovereignty and improve their communities:

- State Recognition: Some states offer their own forms of tribal recognition. While this doesn’t confer federal benefits, it can provide some legal standing within the state, access to state-level resources, and a measure of validation for the community’s identity. Virginia, for instance, has recognized several tribes, some of whom later achieved federal recognition.

- Self-Sufficiency and Economic Development: Many tribes are pursuing their own economic ventures, from small businesses and cultural tourism to agriculture, without federal assistance. They rely on their own ingenuity and community solidarity.

- Cultural Revitalization: Groups are actively engaged in language preservation, traditional arts, and ceremony, ensuring that their heritage is passed down to future generations, regardless of their legal status.

- Advocacy and Lobbying: Non-recognized tribes continuously lobby Congress, advocating for reforms to the BIA recognition process, or seeking direct congressional recognition – a path that bypasses the BIA’s rigorous administrative process but requires significant political will.

- Coalition Building: Many non-recognized tribes are forming alliances and networks to share resources, strategies, and amplify their collective voice.

The Houma Nation of Louisiana, for example, has been seeking federal recognition for decades, a process complicated by historical records lost to hurricanes and the unique challenges of their bayou homeland. Despite this, they maintain a vibrant culture, a strong sense of community, and continue to advocate fiercely for their rights, while also focusing on coastal restoration and cultural preservation efforts in the face of climate change.

A Call for Understanding

The existence of hundreds of non-federally recognized tribes challenges the tidy narrative of Indigenous-U.S. relations. It underscores the enduring legacy of colonialism, the bureaucratic hurdles that obstruct justice, and the sheer resilience of Indigenous peoples. Their struggle is not just about gaining access to federal funds or land; it is fundamentally about the right to self-determination, the acknowledgment of their unique identity, and the preservation of their cultures for future generations.

Understanding non-federally recognized tribes means recognizing that tribal identity is not solely conferred by a government document but is inherent, passed down through generations, and lived out in communities every day. Their fight is a crucial chapter in the ongoing story of American justice and sovereignty, demanding that we look beyond official lists and acknowledge the rich, complex, and often overlooked Indigenous nations that continue to thrive across the land.