Echoes of a Continent: The Enduring Power of Native American Languages

The phrase "Native American dialect" is often uttered with an innocent intent, a seemingly simple descriptor for the rich linguistic heritage of Indigenous peoples in North America. Yet, this seemingly innocuous term carries a profound misunderstanding, one that fundamentally misrepresents the astonishing diversity and complex history of the continent’s first languages. To speak of a single "Native American dialect" is akin to suggesting that all European languages are mere dialects of one another, rather than distinct tongues like French, German, and Russian.

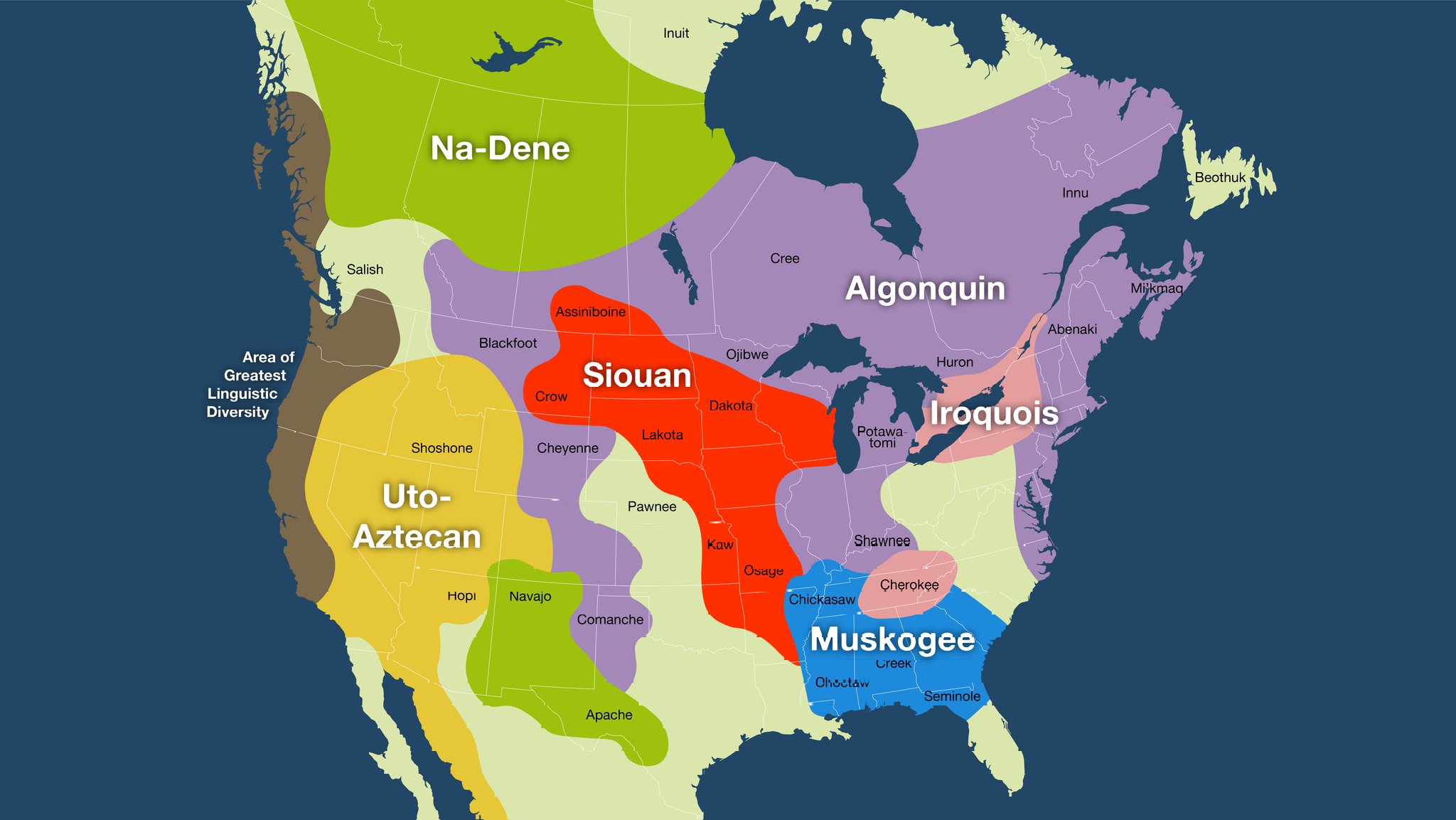

The truth is far more intricate and awe-inspiring: before European contact, North America was a vibrant linguistic mosaic, home to hundreds, possibly thousands, of mutually unintelligible languages, each with its own unique grammar, vocabulary, and worldview. These were not dialects – variations of a single language – but distinct linguistic entities, grouped into dozens of large language families, as different from one another as English is from Chinese.

A Kaleidoscope of Tongues: Beyond the "Dialect" Myth

Imagine a continent where conversations flowed in over 300 distinct languages in what is now the United States and Canada alone, with countless more in Mexico and Central America. The linguistic map of pre-colonial North America was a testament to human ingenuity and cultural adaptation. From the arid deserts of the Southwest to the lush forests of the Northeast, from the icy reaches of the Arctic to the sun-drenched coasts of California, each landscape resonated with its own unique linguistic echo.

These languages belong to over 50 different language families, a level of diversity rarely seen elsewhere on Earth. For perspective, Europe, a continent of comparable size, has only three major language families: Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic (though the latter two are far less widespread). This sheer number of unrelated linguistic groups underscores the fallacy of the "dialect" notion.

Consider the vast differences:

- Navajo (Diné Bizaad): Spoken by the Diné people of the Southwestern United States, Navajo is part of the Na-Dené language family. It’s known for its complex verb structures, tonal qualities (where the pitch of a word changes its meaning), and its historical significance during World War II, when Navajo Code Talkers used their language to create an unbreakable code, a testament to its complexity and obscurity to outsiders.

- Cherokee (Tsalagi Gawonihisdi): An Iroquoian language, Cherokee is famous for its syllabary, invented by Sequoyah in the early 19th century. This writing system allowed the Cherokee people to achieve widespread literacy in their own language in a remarkably short period, leading to the publication of books, newspapers, and even a constitution. Unlike European alphabets, each symbol in the Cherokee syllabary represents a syllable, not a single letter.

- Lakota (Lakȟóta): Part of the Siouan language family, Lakota is spoken by the Lakota people of the Great Plains. It’s known for its rich oral tradition, intricate system of honorifics, and its deep connection to the spiritual and cultural practices of the Plains tribes. Its grammar often reflects a worldview centered on relationships and the natural world.

- Ojibwe (Anishinaabemowin): An Algonquian language spoken across a wide swath of the Great Lakes region, Ojibwe is a polysynthetic language. This means that words are often formed by combining many different morphemes (meaningful units) into long, complex words that can convey an entire sentence’s worth of meaning in English. For example, the Ojibwe word giiwitaashkaagamidegamaa means "it is a lake that has a shoreline all around it."

These examples merely scratch the surface. From the intricate noun cases of Yup’ik to the click consonants once found in some California languages, the linguistic landscape was a treasure trove of human expression, each language a unique lens through which its speakers understood and interacted with the world.

The Great Silence: The Impact of Colonialism and Assimilation

The arrival of European colonizers marked the beginning of a catastrophic period for these languages. Disease, warfare, and forced displacement decimated Indigenous populations and disrupted traditional ways of life, directly impacting language transmission. But it was the deliberate policies of cultural assimilation that dealt the most devastating blows.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, governments in the United States and Canada implemented policies designed to eradicate Indigenous cultures, including their languages. The infamous Indian boarding school system (known as residential schools in Canada) was a primary tool for this cultural genocide. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their native tongues, and often severely punished for doing so. As historian Brenda J. Child notes, "The boarding school experience was designed to sever the intergenerational transmission of language and culture." Children were taught that their languages were "primitive" or "savage," instilling shame and fear.

This systematic suppression had a profound and lasting impact. Generations grew up without learning their ancestral languages, leading to a precipitous decline in fluency. Languages that had thrived for millennia rapidly became endangered, with many falling silent forever. Today, of the hundreds of languages once spoken north of Mexico, only about 150-175 remain, and a vast majority of these are critically endangered, with only a handful of elderly speakers remaining. Experts estimate that without significant intervention, many more will disappear within decades.

The Urgency of Revival: A Fight for Identity and Knowledge

The loss of a language is far more than just the loss of words. As linguist Ken Hale famously stated, "When you lose a language, you lose a culture, a intellectual heritage, a work of art, a view of the world." Each Indigenous language contains unique knowledge systems, historical narratives, spiritual beliefs, and intricate understandings of the natural world that are embedded within its very structure. When a language dies, that unique repository of human knowledge and experience is irretrievably lost.

For many Indigenous communities, language is inextricably linked to identity, sovereignty, and well-being. "Our language is our land; our language is our spirit; our language is who we are," asserted the late Richard Wilson, a prominent elder of the Lakota people. Revitalizing these languages is not merely an academic exercise; it is a profound act of cultural reclamation and self-determination, a healing process for historical trauma, and a vital step towards ensuring the future of Indigenous nations.

The Resurgence: A Tapestry Re-Woven

Yet, across Native North America, a powerful counter-narrative is unfolding – a vibrant movement of language revitalization. Despite centuries of suppression, communities are fighting to bring their languages back from the brink. This resurgence is fueled by an unwavering commitment to cultural survival and a deep understanding of what was lost.

Tribes are investing in a wide array of innovative programs:

- Immersion Schools: Modeled after successful Hawaiian language schools, these institutions teach all subjects entirely in the Indigenous language, creating new generations of fluent speakers. Examples include the Salish School of Spokane, which is producing young fluent speakers of the critically endangered Salish language.

- Master-Apprentice Programs: Fluent elders (the "masters") work one-on-one with dedicated learners (the "apprentices") to transmit the language through daily interaction, focusing on natural conversation in real-life contexts.

- Language Camps and Classes: Community-based programs offer lessons for all ages, from toddlers to adults, often incorporating traditional activities and cultural teachings.

- Technology: Indigenous language apps, online dictionaries, social media groups, and YouTube channels are being developed, making learning resources more accessible than ever before. For example, the Cherokee Nation has developed a popular keyboard app that allows users to type in the Cherokee syllabary.

- Cultural Integration: Languages are being woven back into daily life, traditional ceremonies, tribal governance, and even popular culture, with Indigenous language music, films, and literature emerging.

These efforts face significant challenges: limited funding, the advanced age of many fluent speakers, and the pervasive influence of English. However, the dedication of language warriors, elders, and young learners alike is creating new hope. Children are once again learning their ancestral languages as their first tongue, grandmothers are teaching their grandchildren the songs and stories of their people, and communities are witnessing a slow but steady resurgence of linguistic vibrancy.

Beyond Words: A Unique Worldview

Ultimately, understanding Native American languages goes far beyond recognizing their grammatical complexity or historical fragility. It’s about appreciating the unique worldviews they embody. Many Indigenous languages do not categorize the world in the same way English does. For instance, some focus more on processes and actions than on fixed objects, or they embed respect for the natural world directly into their verb structures.

As Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, eloquently states in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, "Learning the language of the land, the language of the original people, is a pathway to understanding a different way of being." These languages offer alternative philosophies, ethical frameworks, and ways of relating to the environment and each other, providing invaluable perspectives in a world grappling with complex global challenges.

The Future is Spoken

The journey of Native American languages is a testament to both profound loss and incredible resilience. The initial misconception of a singular "dialect" gives way to the breathtaking reality of hundreds of distinct linguistic treasures, each a living archive of history, culture, and knowledge.

Today, the fight to preserve and revitalize these languages is not just about linguistics; it’s about justice, self-determination, and the recognition of Indigenous peoples’ inherent rights. Every new speaker, every revitalized word, is a triumph against historical oppression and a vital step towards ensuring that the echoes of this continent’s first voices continue to resonate for generations to come, enriching not only Native American communities but the entire human family. The future of these languages, once hanging precariously in the balance, is now being actively spoken into existence, one word, one song, one story at a time.