Okay, here is a 1,200-word journalistic article in English on Native American cultural appropriation.

Beyond the Beaded Headdress: Unpacking Native American Cultural Appropriation

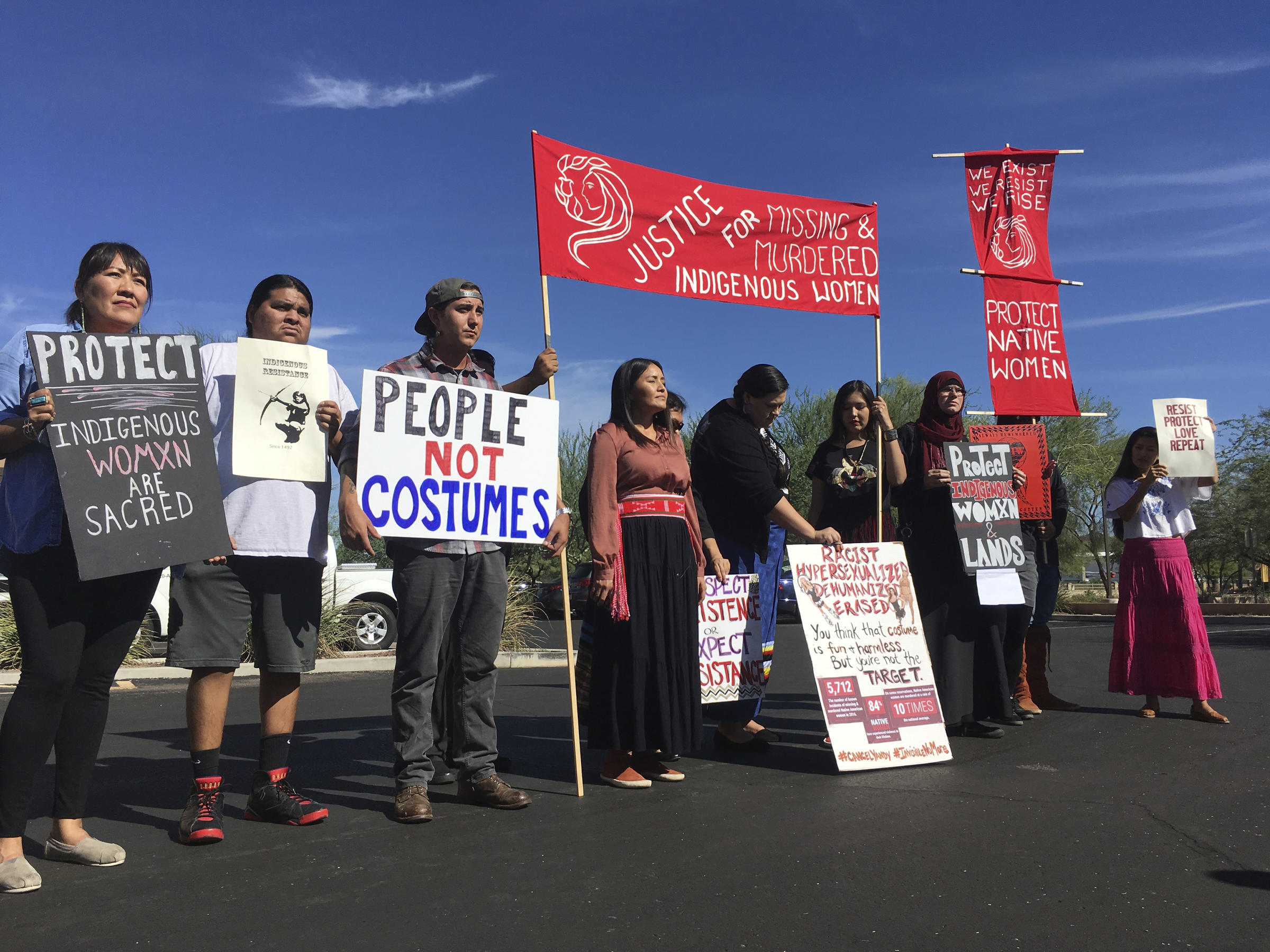

In the bustling marketplaces of tourist traps, alongside the shimmering lights of music festivals, and even within the hallowed halls of professional sports, an unsettling trend persists: the commodification and misrepresentation of Indigenous cultures. While often dismissed as harmless admiration or appreciation, the phenomenon of cultural appropriation, particularly concerning Native American traditions, symbols, and spiritual practices, carries a profound and painful history. It’s a complex issue rooted in centuries of colonization, erasure, and power imbalances, going far beyond just a "costume" or a "trend."

At its core, cultural appropriation refers to the adoption or use of elements of a minority culture by members of the dominant culture, often without understanding, acknowledgment, or respect for the original context, meaning, or creators. When applied to Native American cultures, this isn’t merely a matter of borrowing; it’s a perpetuation of historical injustices where Indigenous peoples have had their lands, languages, and lives taken, only to see their sacred traditions cherry-picked and profited from by outsiders.

The Historical Echo: Why It Hurts Deeper

To understand the gravity of Native American cultural appropriation, one must first acknowledge the brutal historical context. For over 500 years, Indigenous peoples across North America have endured systematic genocide, forced assimilation, land theft, and the deliberate suppression of their cultures. Treaties were broken, children were stolen and sent to boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian, save the man," and spiritual practices were outlawed.

Against this backdrop of immense suffering and ongoing struggle for survival and sovereignty, the act of a non-Native person donning a feather headdress at Coachella, selling "spiritual" dreamcatchers made in a factory, or naming a sports team a derogatory term like "Redskins" isn’t a neutral act. It’s an extension of that historical oppression, trivializing profound spiritual beliefs, reducing complex identities to caricatures, and denying Indigenous peoples control over their own heritage.

Defining the Line: Appropriation vs. Appreciation

A common defense against accusations of appropriation is the claim of "appreciation." However, the distinction is critical. Appreciation involves genuine respect, deep understanding, an invitation from the culture itself, and often, an exchange that benefits the original creators. Appropriation, conversely, typically involves:

- A Power Imbalance: It occurs when a dominant group takes from a marginalized group without consent or reciprocity.

- Commodification and Profit: Elements are often stripped of their original meaning and sold for profit.

- Decontextualization: Sacred or significant items are used out of their original context, losing their spiritual or cultural weight.

- Stereotyping and Erasure: It often reinforces harmful stereotypes and contributes to the invisibility of contemporary Indigenous peoples.

As Dr. Adrienne Keene (Cherokee), an academic and founder of the popular blog Native Appropriations, succinctly puts it, "The difference is one of power. Cultural appropriation is about power. It’s about a dominant group taking from a marginalized group and using it for their own benefit, often without understanding or respect."

Manifestations of Appropriation: From Fashion to Spirituality

The ways in which Native American culture is appropriated are diverse and pervasive:

- Fashion and Adornment: Perhaps the most visible form of appropriation is the casual wearing of Native American-inspired clothing and accessories. The feather headdress, for example, is a deeply sacred item, earned through acts of bravery and service, and typically worn by male leaders within specific Plains tribes. Its casual use by festival-goers or fashion models disrespects its profound spiritual and cultural significance. Similarly, patterns like the "Navajo print," which are often copyrighted and represent specific tribal designs, are frequently copied and mass-produced by major retailers without permission or compensation to the Navajo Nation.

- Sports Mascots and Imagery: The decades-long struggle against professional sports teams using Native American mascots and imagery (e.g., the former Washington Redskins, Cleveland Indians’ Chief Wahoo) is a prime example of appropriation and dehumanization. These caricatures perpetuate harmful stereotypes, reduce diverse peoples to one-dimensional figures, and have a documented negative psychological impact on Indigenous youth, contributing to feelings of discrimination and low self-esteem. As Deborah Parker (Tulalip), former co-chair of the National Congress of American Indians’ "Change the Mascot" campaign, stated, "Our children are learning in schools that we are mascots, not people. This is harmful."

- Spiritual Practices and Wellness Trends: The commercialization of Native American spiritual practices is deeply offensive. Elements like "smudging" (the burning of sacred herbs like sage or cedar for purification), sweat lodge ceremonies, vision quests, and the concept of "spirit animals" have been commodified and sold as wellness trends or New Age spiritual retreats to non-Natives, often by individuals with no legitimate connection to these traditions. These practices are often closed ceremonies, specific to particular tribes, and require years of learning and respect under the guidance of elders. When sold online or offered by unauthorized individuals, their sacred meaning is stripped, and the original practitioners are often left without resources or recognition.

- "Native-Inspired" Decor and Art: Dreamcatchers, once a protective charm woven by the Ojibwe people for their children, are now mass-produced in factories worldwide and sold as generic wall decor. Totem poles, specific to Pacific Northwest Indigenous cultures, are sometimes misrepresented or imitated out of context. This proliferation of inauthentic items not only exploits Indigenous designs but also drowns out the voices and economic opportunities of legitimate Native artists and craftspeople.

- Halloween Costumes: The ubiquitous "sexy Pocahontas" or "Indian chief" costumes are another annual flashpoint. These costumes reduce complex histories and diverse cultures to offensive caricatures, reinforcing racist tropes and trivializing the real struggles of Indigenous peoples.

The Deep Wounds: Why It Matters So Much

The harm caused by cultural appropriation is multifaceted:

- Economic Exploitation: Indigenous artists and businesses lose out when their designs and practices are stolen and mass-produced by large corporations without compensation or permission.

- Perpetuation of Stereotypes: It reinforces harmful, often romanticized or derogatory, stereotypes that deny the contemporary existence and diversity of Native American peoples. It reduces living cultures to relics of the past.

- Erasure and Invisibility: When non-Natives claim elements of Indigenous culture, it can further marginalize and silence Native voices, making it harder for authentic stories and traditions to be heard and understood.

- Trivialization of the Sacred: For many Indigenous communities, certain objects, symbols, and ceremonies are deeply sacred, imbued with spiritual power and ancestral knowledge. Their casual or disrespectful use is akin to desecration.

- Psychological Toll: For Indigenous individuals, witnessing their culture being trivialized, misrepresented, or stolen can be deeply painful, contributing to feelings of anger, frustration, and alienation. It’s a constant reminder that their identity is not respected or understood by the broader society.

Moving Forward: Towards Respect and Reciprocity

Addressing Native American cultural appropriation requires a shift in mindset and practice, moving from taking to learning and supporting.

- Educate Yourself: Learn about the specific Indigenous peoples whose lands you occupy. Understand their history, their contemporary struggles, and their distinct cultures. Resources like Native-led organizations, academic works, and tribal websites are invaluable.

- Listen to Native Voices: Prioritize and amplify the voices of Indigenous artists, scholars, activists, and community leaders. If a Native person tells you something is offensive or inappropriate, listen and respect their perspective.

- Support Native Creators: If you admire Indigenous art or craftsmanship, seek out and purchase directly from authentic Native artists, designers, and businesses. This ensures that the economic benefit goes directly to the creators and their communities. Look for certifications or buy from reputable Native-owned platforms.

- Seek Permission, Not Just Information: For deeper engagement, particularly with spiritual or ceremonial practices, true appreciation often involves an invitation from the community itself. These are not open for casual adoption.

- Challenge Misrepresentation: Speak up when you see instances of appropriation, whether it’s a problematic costume, a racist mascot, or a company profiting from stolen designs.

- Understand the "Why": Always remember that appropriation isn’t just about an item or a symbol; it’s about the historical context, the power dynamics, and the ongoing impact on a marginalized community that has already lost so much.

Ultimately, understanding Native American cultural appropriation is not about policing individual actions, but about recognizing a systemic issue rooted in colonialism and advocating for a future where Indigenous cultures are respected, protected, and celebrated on their own terms, by their own people. It’s about ensuring that the rich, diverse, and vibrant heritage of Native America is seen, heard, and honored authentically, beyond the beaded headdress and the appropriated symbol.