The Enduring Spirit of the Bah-Kho-Je: A History of the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma

The name "Iowa" often conjures images of endless cornfields and the heartland of America. Yet, long before European settlers charted its fertile plains, this land, and indeed much of the Midwest, was the ancestral home of a vibrant and resilient people known as the Bah-Kho-Je, or the Iowa Tribe. Their journey, marked by forced displacement, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to their heritage, is a powerful testament to the enduring spirit of Native American nations. The history of the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma, distinct from their relatives in Kansas and Nebraska, is a narrative of profound change, loss, and ultimately, a remarkable resurgence.

I. Origins and Early Flourishing: The People of the Gray Snow

The Iowa people, one of the Chiwere Siouan-speaking tribes, trace their origins to the Great Lakes region, sharing linguistic and cultural ties with the Otoe, Missouri, and Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) tribes. Their name, Bah-Kho-Je, is often translated as "people of the gray snow" or "dusted ones," perhaps referring to their traditional winter lodges covered in snow or their unique manner of painting their faces. For centuries, they thrived as a semi-nomadic people, blending sophisticated agricultural practices with skilled hunting.

Their villages, typically located near rivers like the Mississippi and Missouri, were centers of corn, bean, and squash cultivation. But their lives were also inextricably linked to the vast herds of buffalo that roamed the prairies. Seasonal buffalo hunts were crucial for sustenance, clothing, and tools, dictating a rhythm of life that balanced settled village life with expansive treks across their vast territories, which once encompassed parts of present-day Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Kansas, and Nebraska. Their society was structured around clans, each with specific responsibilities and traditions, governed by a council of chiefs and elders, ensuring a strong communal identity and spiritual connection to their land.

II. The Gathering Storm: European Contact and Westward Pressure

The arrival of Europeans in North America irrevocably altered the trajectory of the Iowa Tribe. First came the French in the late 17th century, bringing trade goods like firearms and metal tools, but also devastating diseases against which the Iowa had no immunity. Smallpox, measles, and influenza swept through their communities, decimating populations and disrupting social structures. The fur trade, while offering new commodities, also intensified inter-tribal conflicts over hunting grounds as demand for beaver pelts soared.

As the 18th century progressed, the French gave way to the Spanish and then, critically, to the burgeoning United States. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 placed the Iowa squarely within the path of American westward expansion. The U.S. government, driven by a policy of "Indian Removal," began to exert immense pressure on tribes to cede their ancestral lands. For the Iowa, this process unfolded through a series of treaties, each one chipping away at their territory.

One of the most significant figures during this turbulent period was Chief Mahaska (also known as White Cloud). A pragmatic and eloquent leader, Mahaska understood the futility of armed resistance against the overwhelming American military might. He advocated for peace and sought to secure the best possible terms for his people, even traveling to Washington D.C. in 1824 to negotiate directly with President James Monroe. Despite his efforts, the relentless push for land continued. A poignant quote attributed to Mahaska, reflecting the despair of his people, captures this era: "Our homes are gone, our hunting grounds are gone, and soon our people will be gone too."

By the early 19th century, treaties signed in 1824, 1830, and 1836 systematically reduced the Iowa’s vast domains to a small reservation straddling the border of what would become Kansas and Nebraska. This drastic reduction of territory severely curtailed their traditional hunting and farming practices, forcing them into a sedentary life that was increasingly reliant on federal annuities and supplies, often delivered inconsistently and of poor quality.

III. The Great Divide: Relocation to Indian Territory

Life on the Kansas-Nebraska reservation proved to be a crucible for the Iowa people. Crowding, disease, dwindling resources, and the persistent efforts of missionaries to assimilate them into American society created deep internal divisions. Two main factions emerged: one group, often referred to as the "Christian" or "progressive" band, sought to adapt more fully to American ways, embracing farming techniques and formal education. The other, the "traditional" or "Little Priest" band (named after their leader, who succeeded Mahaska), clung fiercely to their ancestral customs, language, and spiritual practices, resisting assimilation.

The pressures from encroaching white settlers, who eyed even the small reservation lands, intensified the desire for change. The federal government, meanwhile, was pursuing its policy of relocating tribes to "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma), believing it to be a permanent solution to the "Indian problem."

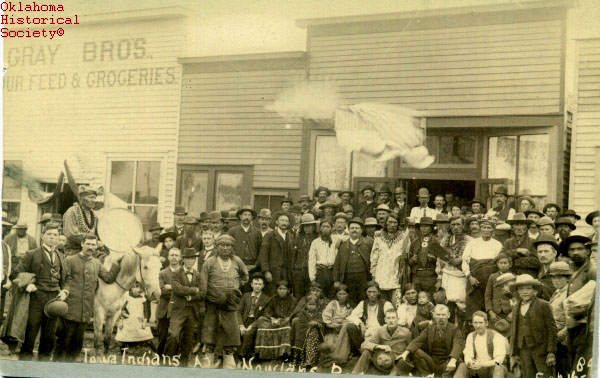

In 1878, a pivotal moment occurred. After years of internal debate and external pressure, the traditional band, led by Chief David Tohee (son of Little Priest), made the momentous decision to relocate south to Indian Territory. They sought a place where they could live freely, practice their ceremonies, and raise their children away from the pervasive influence of white society. This move solidified the split within the Iowa Nation, giving rise to two distinct federally recognized tribes: the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, and the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

The journey to Indian Territory was arduous, a "trail of tears" for the Iowa. They traveled by wagon and on foot, enduring hardship, disease, and the trauma of leaving behind generations of ancestors and familiar landscapes. Upon their arrival in 1879, they were settled on a new reservation in what would become Lincoln, Payne, and Logan counties in central Oklahoma. This new homeland, though different, offered a semblance of peace and a chance to rebuild.

IV. Allotment and Assimilation: A New Threat in Oklahoma

The relative peace in Indian Territory was short-lived. The late 19th century brought another devastating federal policy: the Dawes Act of 1887, also known as the General Allotment Act. This act aimed to break up tribal communal landholdings and assign individual plots of land to Native Americans, with the stated goal of encouraging assimilation into American farming society and "civilizing" them.

For the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma, the Dawes Act was catastrophic. Their 200,000-acre communal reservation was dissolved, and each tribal member was allotted a specific acreage – typically 80 or 160 acres. The "surplus" land, often the most valuable, was then opened up to white settlement through land runs and lotteries, effectively dispossessing the tribe of the vast majority of their land base. The Iowa’s land base dwindled to a mere fraction of its former size.

The impact of allotment was profound. It shattered the communal fabric of Iowa society, making traditional hunting impractical and forcing many into poverty. Many allotments were quickly lost through fraudulent schemes, taxation, or inability to make the land productive. Children were sent to boarding schools, where their hair was cut, their traditional clothing replaced, and they were forbidden to speak their language or practice their customs. The explicit goal was to "kill the Indian to save the man," a policy that inflicted deep psychological and cultural wounds.

V. Reorganization and Resurgence: The Road to Self-Determination

The early 20th century was a period of immense struggle for the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma. Yet, their spirit of resilience never truly faltered. The tide began to turn with the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. While imperfect, the IRA ended the disastrous allotment policy and encouraged tribes to reorganize their governments under written constitutions.

The Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma seized this opportunity. In 1937, they formally adopted a constitution and bylaws, establishing a democratically elected tribal council and laying the groundwork for modern self-governance. This was a crucial step in reclaiming their sovereignty and rebuilding their community. Over the following decades, the tribe slowly began to assert its rights, establish tribal programs, and work towards cultural revitalization.

The latter half of the 20th century saw a renewed emphasis on self-determination. The Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma, like many other Native nations, began to leverage their inherent sovereignty to pursue economic development and strengthen their tribal infrastructure. The landmark Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 provided a significant economic opportunity. In 1996, the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma opened the Bah-Kho-Je Casino, a vital enterprise that has generated much-needed revenue for tribal services, education, and cultural preservation.

VI. The Modern Bah-Kho-Je Nation: Preserving the Past, Building the Future

Today, the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma stands as a testament to the enduring strength and adaptability of Native American people. Headquartered near Perkins, Oklahoma, the tribe actively works to provide for its members and preserve its rich heritage.

Economic development remains a priority, with the Bah-Kho-Je Casino and other enterprises providing employment and funding essential tribal programs. These include comprehensive healthcare services, educational scholarships, housing assistance, and elder care. The tribe also manages its own law enforcement and judicial systems, further demonstrating its commitment to self-governance.

Crucially, the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma is deeply committed to cultural preservation. Efforts are underway to revitalize the nearly lost Chiwere language through language classes and immersion programs. Traditional ceremonies, once suppressed, are now openly practiced and celebrated, reconnecting younger generations with their ancestral roots. The tribe actively promotes its history through its tribal museum and cultural events, ensuring that the stories of the Bah-Kho-Je are never forgotten. As the tribe’s official website states, their mission is to "preserve our culture and heritage while providing for the needs of our people, both present and future."

The history of the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma is not merely a chronicle of hardship and loss, but a powerful narrative of survival, resilience, and resurgence. From their ancient origins in the Great Lakes to their forced migrations and the challenges of assimilation, the Bah-Kho-Je have demonstrated an unwavering determination to maintain their identity and sovereignty. Their journey mirrors the broader experience of Native Americans in the United States, reminding us of the profound impact of historical policies and the incredible strength of spirit that continues to define indigenous nations today. The Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma stands as a vibrant, self-sufficient nation, honoring their past while building a bright future for the "people of the gray snow."