What is Native American Art? A Living Tapestry of Culture, Resilience, and Identity

In the sprawling galleries of museums and the hushed halls of auction houses, Native American art often commands a reverent silence. Yet, to truly understand its essence, one must look beyond the glass cases and price tags, beyond the simplistic labels of "craft" or "folk art." Native American art is not merely an aesthetic endeavor; it is a profound, living, and continuously evolving tapestry woven from the threads of history, spirituality, community, and an unyielding connection to the land. It is a language spoken through materials, a narrative told across generations, and a powerful assertion of identity in the face of immense change.

To begin, it is crucial to dismantle a common misconception: there is no single "Native American art." The term itself is a broad umbrella, encompassing an astonishing diversity of artistic traditions from over 570 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone, each with its unique cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and artistic expressions. From the intricate basketry of the California tribes to the monumental totem poles of the Pacific Northwest, the vibrant pottery of the Southwest Pueblos to the powerful ledger art of the Plains nations, the variations are as vast and varied as the landscapes these peoples have inhabited for millennia.

Art as Life: Function, Spirituality, and Storytelling

For Indigenous peoples, art has historically been, and largely remains, inseparable from daily life and spiritual practice. Unlike Western art traditions that often separate art from utility, many Native American art forms are inherently functional. A beautifully coiled basket might serve to gather berries or store grain; a meticulously woven blanket provides warmth and tells stories through its patterns; a carved wooden mask embodies a spirit for a ceremonial dance. The "art for art’s sake" concept is largely foreign. Instead, the beauty and power of an object are intrinsically linked to its purpose, its creation process, and its spiritual significance.

Consider the act of creation itself. For many Native artists, the process is deeply spiritual. Materials are often sourced directly from the land—clay from riverbeds, wool from sheep, wood from forests, quills from porcupines. There is a profound respect for these materials, often seen as gifts from the Creator, imbued with their own spirit. The artist acts as a conduit, transforming these gifts into objects that serve, protect, adorn, or heal. The Navajo weaver, for instance, might incorporate a "spirit line" into a rug, an intentional imperfection that allows the weaver’s spirit to escape the piece, or allows the beauty of the piece to continue to evolve. This reflects a holistic worldview where humans, nature, and the spiritual realm are interconnected.

Art also serves as a vital mnemonic device, a repository of history, myth, and genealogy. Winter counts, traditionally painted on hide by Plains tribes, documented the significant events of each year, serving as historical records. Petroglyphs and pictographs etched onto rock faces across the continent narrate ancient journeys, spiritual visions, and astronomical observations. Storytelling is woven into the very fabric of the art, ensuring that cultural knowledge is transmitted from elders to youth, maintaining continuity through generations.

A Kaleidoscope of Regional Styles

To appreciate the breadth of Native American art, a brief journey across some key regions reveals distinct aesthetics and techniques:

- Southwest: Home to the Pueblo peoples (Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Santa Clara, etc.) and the Navajo (Diné), this region is renowned for its pottery (distinctive shapes, intricate designs, varying firing techniques), turquoise and silver jewelry, and the iconic Navajo rugs and blankets. The patterns in Navajo weaving often represent sacred mountains, lightning, or other elements of their cosmology, while Pueblo pottery designs frequently reflect ancestral motifs and agricultural themes.

- Pacific Northwest Coast: From the Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka’wakw, and others, comes art characterized by powerful, curvilinear forms, often in red and black. Totem poles, carved masks for ceremonial dances, bentwood boxes, and button blankets are hallmarks. These pieces frequently depict crest animals and mythical beings, embodying clan lineages and spiritual narratives.

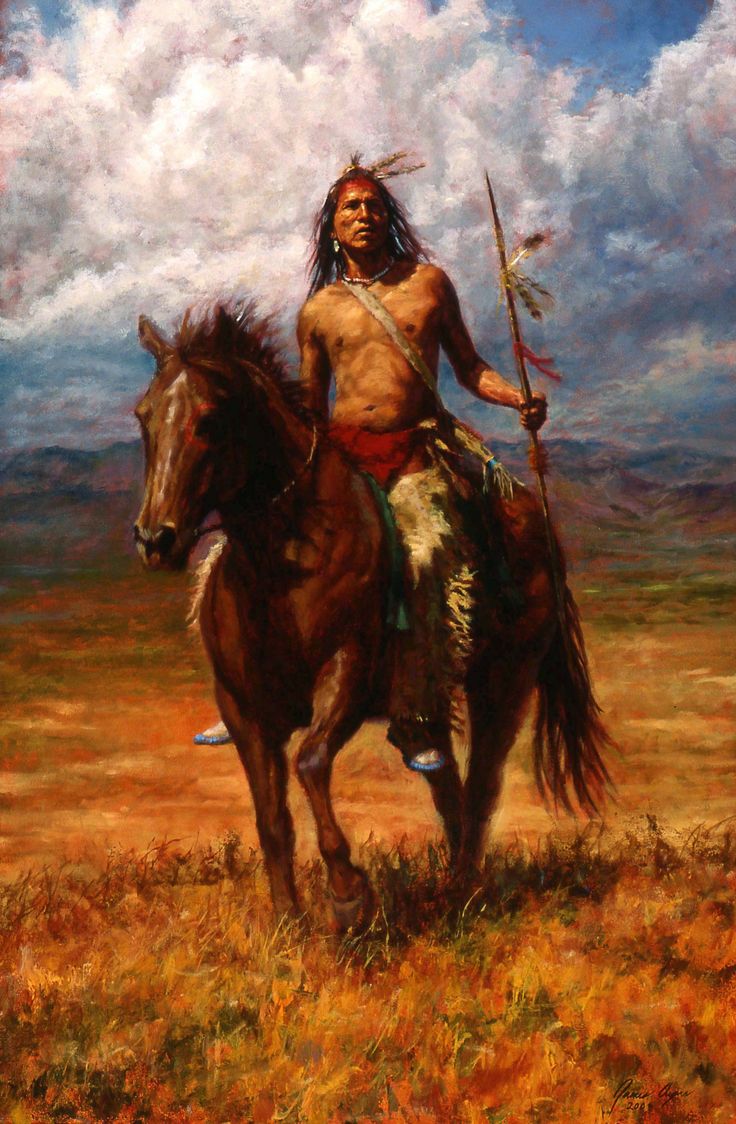

- Plains: The Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, Blackfeet, and others developed a distinct artistic tradition rooted in their nomadic lifestyle and buffalo culture. Beadwork (often floral or geometric, adorning clothing, bags, and ceremonial objects), quillwork (using dyed porcupine quills flattened and sewn onto hide), and hide painting (depicting battles, hunts, or spiritual visions) are prominent. After the buffalo were decimated and tribes confined to reservations, a new form emerged: ledger art, where artists drew on ledger books and other available paper, continuing their narrative traditions in a new medium.

- Eastern Woodlands & Great Lakes: Tribes like the Iroquois, Anishinaabe, Cherokee, and Seminole crafted exquisite wampum belts (shell beads used for treaties and historical records), intricate basketry from various plant fibers, detailed quillwork and beadwork on birchbark and hide, and carved wooden masks (like the Iroquois False Face Masks). Their art often reflects the abundant natural resources of their forested homelands.

Resilience and Transformation: Art in the Face of Adversity

The arrival of European colonizers brought devastating changes: disease, warfare, forced relocation, and cultural suppression. Yet, Native American art did not simply wither away. It adapted, demonstrating an incredible resilience. New materials, introduced by Europeans, were integrated and transformed. Glass beads, for instance, replaced porcupine quills in many areas, leading to new forms and intricate designs in beadwork. Silver, introduced to the Southwest by the Spanish, became a staple for Navajo and Zuni jewelers, who developed unique techniques and styles.

This adaptation was not merely about materials; it was about survival. Art became a quiet act of resistance, a way to maintain cultural identity and continuity when overt expressions were suppressed. The beauty of a piece could mask its deeper cultural meaning from an unsympathetic gaze, while its creation sustained the spirit and knowledge of the community.

Contemporary Native American Art: Bridging Worlds

The 20th century witnessed a significant shift with the rise of contemporary Native American art. Institutions like the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, founded in 1962, played a crucial role in fostering a new generation of artists who blended traditional aesthetics with modern art movements. These artists, often formally trained, began to experiment with new mediums—oil painting, sculpture, photography, performance art, digital art—while continuing to draw inspiration from their cultural heritage.

Today, contemporary Native artists are active participants in the global art scene, exhibiting in major galleries and museums worldwide. Artists like Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish/Kootenai), Kay WalkingStick (Cherokee Nation), Fritz Scholder (Luiseño), T.C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo), and Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Unangax̂) tackle complex themes: identity, sovereignty, environmentalism, historical trauma, cultural appropriation, and the ongoing challenges and triumphs of Indigenous peoples. They critique colonial narratives, reclaim their histories, and envision a vibrant future, using art as a powerful tool for social commentary and decolonization. Their work often challenges stereotypes, insisting on the dynamism and contemporaneity of Native cultures.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite its richness and vitality, Native American art faces ongoing challenges. Cultural appropriation remains a significant concern, with non-Native artists and designers often "borrowing" Indigenous motifs without understanding or crediting their cultural significance, or worse, profiting from designs that are sacred or tied to specific tribal intellectual property. The market is also plagued by fake "Native-made" goods, often mass-produced overseas, which undermine authentic Indigenous artists and mislead consumers. The Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990 was enacted to combat this, making it illegal to market products as "Indian made" if they are not produced by a certified member of a federally or state-recognized tribe, or a certified Indian artisan.

Furthermore, the issue of repatriation—the return of sacred objects and ancestral remains from museums and private collections to their rightful communities—is a continuous struggle.

Conclusion

Native American art is far more than a collection of beautiful objects. It is a testament to the enduring human spirit, a vibrant record of diverse cultures, and a living testament to resilience. It speaks of deep connections to the land, of spiritual reverence, of communal memory, and of an ongoing dialogue with history and the future. From the ancient petroglyphs to the cutting-edge digital art of today, Native American art continues to evolve, innovate, and tell essential stories. To truly appreciate it is to understand its profound cultural significance, to respect the hands that create it, and to recognize its ongoing power as a voice for identity, sovereignty, and the rich legacy of Indigenous peoples. It is a call to listen, learn, and engage with a tradition that is as ancient as the continent itself, yet as contemporary as tomorrow.