The Resilient Tapestry: Unraveling Native American Identity in Modern Society

In the bustling arteries of American cities and across the vast, often remote landscapes of reservations, a complex and vibrant understanding of identity is continuously being forged: that of the Native American. Far from a monolithic construct, Native American identity in modern society is a dynamic, multi-faceted tapestry woven from threads of ancient traditions, enduring sovereignty, profound resilience against historical trauma, and a forward-looking embrace of contemporary challenges and opportunities. It is an identity that defies simple definitions, a testament to the perseverance of hundreds of distinct nations in the face of centuries of systemic oppression and cultural erasure.

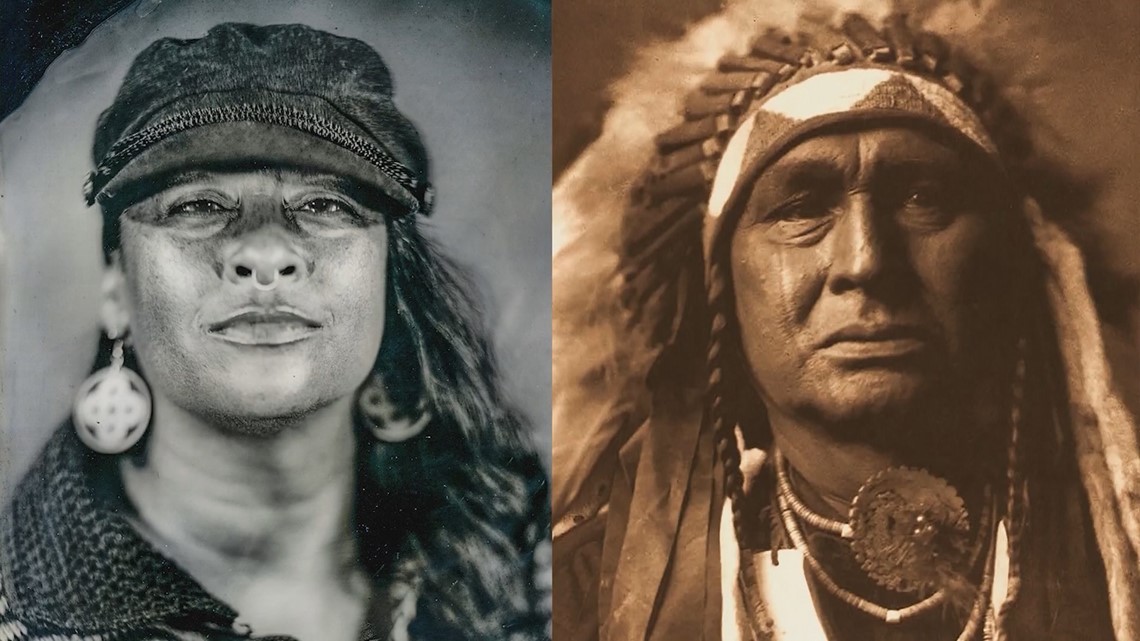

To truly grasp what it means to be Native American today, one must first acknowledge the shadow of history, yet pivot quickly to the bright, unyielding flame of the present. The narrative of Indigenous peoples in America has too often been told through the lens of conquest and victimhood, reducing vibrant cultures to static, romanticized images of the past. The reality, however, is one of continuous adaptation, political struggle, cultural revitalization, and an unwavering connection to land, community, and ancestral knowledge.

Beyond the Stereotype: A Spectrum of Nations

Perhaps the most crucial starting point is to discard the generalized term "Native American" itself, recognizing that it encompasses over 574 federally recognized tribes, and many more state-recognized or unrecognized groups, each with its own unique language, spiritual beliefs, governance structures, artistic expressions, and culinary traditions. From the desert communities of the Diné (Navajo) in the Southwest to the fishing villages of the Pacific Northwest Coast tribes, and the urban enclaves of the Lakota or Cherokee, the experience of being Indigenous is incredibly diverse.

"We are not a monolith," states Dr. Joely Proudfit (Luiseño), Chair of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos. "Our identities are rooted in our tribal affiliations, our familial lineages, and our specific cultural practices. While there are shared experiences of colonialism and resilience, the everyday lived reality of a member of the Seminole Nation in Florida is vastly different from that of a Yup’ik person in Alaska." This diversity is a source of immense strength, but also presents challenges in pan-Indian movements and in advocating for unified policy.

Sovereignty: The Bedrock of Modern Identity

At the heart of modern Native American identity lies the concept of sovereignty. Unlike other ethnic minority groups in the United States, Indigenous nations possess a unique political status as distinct, self-governing entities with inherent rights predating the formation of the U.S. This "nation-to-nation" relationship, though frequently violated throughout history, remains the legal and political bedrock of tribal existence.

The exercise of sovereignty manifests in various ways: tribal courts and law enforcement, tribally run schools and healthcare systems, environmental regulatory bodies, and economic enterprises, most notably gaming. These enterprises, often controversial, provide critical revenue that tribes reinvest in their communities, funding essential services that state and federal governments have historically failed to adequately provide.

"Sovereignty isn’t just a legal term; it’s a living, breathing aspect of who we are," explains Bryan Newland (Bay Mills Indian Community), Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs. "It means the right to determine our own futures, to protect our lands and cultures, and to raise our children in ways that reflect our values. It’s about self-determination, plain and simple." The ongoing legal battles over land rights, water rights, and jurisdiction underscore the continuous struggle to uphold and expand this fundamental aspect of identity.

Cultural Revitalization: Reclaiming What Was Lost

Centuries of forced assimilation policies, most devastatingly the Indian boarding school era (late 19th to mid-20th century), aimed to "kill the Indian, save the man," as famously articulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their languages, practice their spiritual beliefs, or wear their traditional clothing. The devastating intergenerational trauma from these policies continues to impact communities today.

Yet, in a powerful act of resistance and renewal, Native communities are leading vibrant cultural revitalization movements. Language immersion schools are bringing back critically endangered languages. Traditional ceremonies, once driven underground, are openly practiced and celebrated. Ancestral lands are being reclaimed and restored. Artistic expressions – from traditional crafts to contemporary art, music, and literature – are flourishing, telling stories in authentic Native voices.

The Wampanoag Language Reclamation Project in Massachusetts, which has brought the Wôpanâak language back from dormancy, is a powerful example. Jessie Little Doe Baird, a MacArthur Fellow, learned her ancestral language through painstaking research of historical documents and has taught it to a new generation, including her own daughter. This commitment to cultural heritage is not merely nostalgic; it is about strengthening community bonds, fostering a sense of belonging, and healing historical wounds.

The Urban Indian Experience: Identity Beyond the Reservation

While reservations are often the mental image associated with Native Americans, a significant and growing percentage of Indigenous people live in urban areas. The 2020 U.S. Census revealed that 71% of American Indians and Alaska Natives live in urban or suburban areas. This urban migration, often driven by economic opportunities or educational pursuits, creates a distinct set of identity dynamics.

For many urban Indians, identity is maintained through intertribal community centers, powwows, and cultural events that bring together individuals from diverse tribal backgrounds. While they may be physically removed from their ancestral lands or tribal governments, technology and travel allow for continued connection. The challenge for urban Natives often lies in navigating the complexities of their tribal affiliations while simultaneously building pan-Indian solidarity and fighting for recognition and resources in cities not traditionally designed to serve their unique needs.

Navigating Blood Quantum and Belonging

One of the most contentious and internally debated aspects of modern Native identity is the concept of blood quantum, a measurement of the percentage of one’s "Indian blood." Originally imposed by the U.S. government to define who was "Indian enough" to inherit land or receive treaty benefits, it has been adopted by many tribes as a criterion for tribal enrollment.

This system, a colonial construct, has created complex questions of belonging, particularly for individuals with mixed heritage or those who were disconnected from their tribal communities due to adoption or other circumstances. Some argue it’s necessary for tribal self-preservation, ensuring resources are distributed to those with direct lineage. Others contend it’s a divisive tool that perpetuates the very genocidal goals of the past, limiting tribal growth and excluding individuals who identify strongly with their heritage but don’t meet arbitrary blood quantum requirements.

As author Rebecca Roanhorse (Ohkay Owingeh/Lakota) eloquently puts it, "Identity is not measured in percentages on a piece of paper. It’s in the stories you know, the ceremonies you participate in, the land you walk, and the community you serve." This sentiment reflects a growing movement to redefine identity based on cultural connection, community engagement, and lineal descent, rather than a numerical fraction.

Challenges and Resilience: A Forward Look

Despite the vibrancy and resilience, modern Native American identity is inextricably linked to ongoing challenges. Socioeconomic disparities persist, with Indigenous communities often facing higher rates of poverty, unemployment, and health issues like diabetes and heart disease. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) crisis highlights the disproportionate violence faced by Native women and girls, a stark reminder of the continued vulnerability and lack of justice. Environmental injustices, such as the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock, underscore the deep spiritual and cultural connection to land and water, and the ongoing fight to protect it from exploitation.

Yet, in these very struggles, Native American identity is affirmed and strengthened. Activism, particularly among younger generations, is vibrant and effective, utilizing social media and global platforms to advocate for their rights, challenge stereotypes, and promote their cultures. Native voices are increasingly being heard in politics, academia, arts, and media, breaking down barriers and shaping public perception. The appointment of Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) as the first Native American Cabinet Secretary (Secretary of the Interior) is a powerful symbol of this growing influence and representation.

In conclusion, Native American identity in modern society is not a relic of the past, nor is it a monolithic concept. It is a living, breathing, evolving force, shaped by profound historical trauma but defined by unparalleled resilience, vibrant cultural revival, the ongoing assertion of sovereignty, and an unwavering commitment to community and land. It is an identity that continues to challenge conventional narratives, demanding recognition, respect, and a place at the forefront of American society, not as a fading memory, but as a vital and enduring presence. The tapestry of Indigenous identity is still being woven, richer and more complex with each passing generation, proving that despite everything, Indigenous nations are not just surviving; they are thriving.