Beyond Dogma: Exploring Native American Spirituality vs. Religion

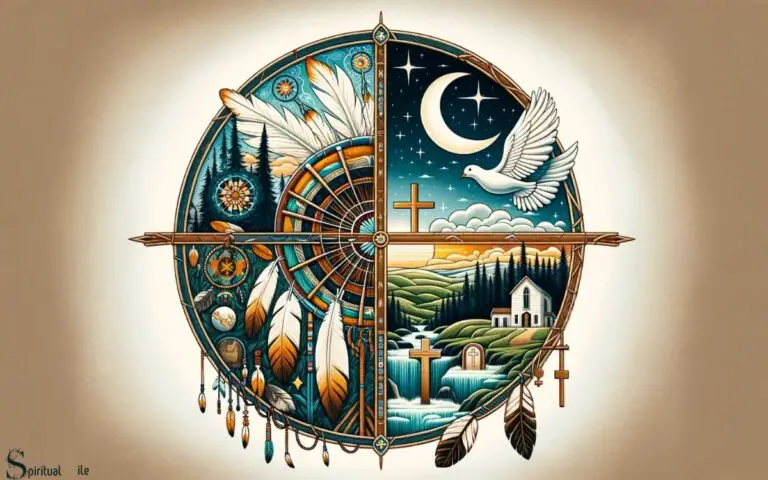

The very phrase "Native American religion" often triggers a subtle discomfort among Indigenous peoples and those who genuinely seek to understand their rich cultural heritage. For many, the concept of "religion," as understood in the Western sense, fails to capture the profound, holistic, and deeply integrated nature of Indigenous ways of knowing and being. Instead, the term "spirituality" is far more fitting, highlighting a fundamental distinction that goes to the heart of worldview, practice, and relationship with the world.

This article delves into that crucial difference, exploring why Native American traditions are more accurately described as spiritual paths rather than religions, and what unique characteristics define these vibrant, enduring expressions of human connection to the sacred.

The Western Construct of "Religion"

To understand why "religion" falls short, we must first examine its typical Western definition. Historically, Western religions – particularly the Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam – are often characterized by:

- Fixed Dogma and Creed: A set of prescribed beliefs, doctrines, and tenets that adherents must accept as truth.

- Sacred Texts: Holy scriptures (e.g., Bible, Torah, Quran) that serve as foundational sources of divine revelation and moral guidance.

- Institutional Structures: Hierarchical organizations, churches, mosques, synagogues, and a formal clergy that mediate between individuals and the divine.

- Proselytization: An emphasis on converting others to the faith, often viewing it as the sole path to salvation or truth.

- Separation of Sacred and Profane: A distinction between the holy (God, heaven, church) and the mundane (daily life, nature, secular world).

- Linear Time and Eschatology: A focus on a historical progression with a definite beginning and end, often culminating in a judgment or ultimate destiny.

These characteristics, while defining for many global faiths, simply do not align with the diverse spiritual expressions of Indigenous North America.

Why "Spirituality" Resonates More Deeply

For Native American peoples, the word "religion" carries the heavy baggage of colonial history – forced conversions, the suppression of traditional practices, and the imposition of foreign belief systems in boarding schools where Indigenous languages and ceremonies were brutally outlawed. To call their traditions "religion" is, for many, to unwittingly participate in that historical erasure.

Instead, "spirituality" better encapsulates a worldview where the sacred is not separate from daily life, but rather interwoven into every aspect of existence. It is not about believing in a set of doctrines, but about living a way of life that fosters harmony, balance, and respect. As many Indigenous elders articulate, "We don’t have a word for religion. We have a way of life." This "way of life" is characterized by:

1. Interconnectedness and Holistic Living

At the core of Native American spirituality is the profound understanding that everything is interconnected. Humans are not superior to nature but are an integral part of the "Sacred Hoop" or "Web of Life." This includes the land, water, animals, plants, sky, ancestors, and future generations. Every action has consequences for the whole.

"We are a part of the earth, and the earth is a part of us," declared Chief Seattle (though the exact quote is debated, the sentiment is authentically Indigenous). This deep ecological consciousness means that care for the environment is not an ethical choice but a spiritual imperative, an act of kinship and reciprocity. There is no concept of "dominion over" nature; rather, it is about living with nature in respectful balance.

2. Reciprocity and Respect

The relationship with the spiritual world, and indeed with all of existence, is founded on reciprocity. Giving thanks, offering prayers, and participating in ceremonies are not just rituals but acts of giving back for what has been received. This extends to hunting, gathering, and even speaking – every interaction is approached with gratitude and respect for the spirit inherent in all things.

For example, when a hunter takes an animal, traditional practices often involve giving thanks to the animal’s spirit, using every part of the animal, and offering tobacco or a prayer in return, acknowledging the sacrifice that sustains life. This is not a detached belief but an active, participatory relationship.

3. Cyclical Time and Renewal

Unlike the linear progression of Western thought, many Indigenous traditions embrace a cyclical understanding of time. Life, death, and rebirth are seen as continuous cycles, mirroring the seasons, the moon phases, and the patterns of the natural world. Ceremonies often align with these cycles, marking solstices, equinoxes, harvests, and planting times, reinforcing the community’s connection to the rhythms of the earth. This cyclical view emphasizes renewal, continuity, and the eternal nature of the spirit.

4. Oral Tradition and Storytelling

Knowledge, wisdom, and spiritual teachings are primarily transmitted through oral tradition, storytelling, songs, and ceremonies. Elders are the living libraries, holding generations of accumulated wisdom. Stories are not just entertainment; they are living repositories of history, ethics, cosmology, and spiritual guidance, often adapting slightly with each telling to remain relevant to contemporary contexts. This dynamic, living transmission contrasts sharply with fixed, written scriptures.

5. Land as Sacred Pedagogy

The land itself is a teacher, a library, and a sacred space. Specific geographical features – mountains, rivers, lakes, forests – hold deep spiritual significance, often being the sites of ceremonies, vision quests, or the homes of powerful spirits. The spiritual practices are deeply rooted in the specific ecosystems and histories of the tribal nations. Disconnecting people from their ancestral lands is thus not just a physical displacement but a spiritual trauma, severing their connection to their identity and their source of spiritual knowledge.

6. Community and Ancestors

Spirituality is often communally practiced and deeply intertwined with family, clan, and tribal identity. The well-being of the individual is inseparable from the well-being of the community. Ancestors play a vital role, not as distant figures but as active presences whose wisdom and guidance continue to influence the living. Honoring ancestors is a continuous practice, reinforcing identity and continuity.

Practices and Ceremonies: Living the Spirituality

Native American spiritual practices are diverse, varying significantly from one tribal nation to another, but they share common threads of purpose: to connect with the spiritual realm, maintain balance, heal, give thanks, and ensure the well-being of the community. Examples include:

- The Sweat Lodge (Inipi): A powerful purification ceremony found across many tribes, involving heat, steam, water, and prayer within a dome-shaped lodge, symbolizing a return to the womb of Mother Earth.

- Vision Quest: A solitary spiritual journey, often involving fasting and meditation in nature, undertaken to seek guidance, a personal spiritual helper, or a life purpose.

- Sun Dance: A central ceremony for many Plains tribes, involving sacrifice, prayer, and communal gathering over several days, often for healing and renewal of the people and the earth.

- Peyote Way (Native American Church): A relatively newer spiritual path, incorporating the sacramental use of peyote for healing and spiritual insight. Its legal protection under the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) amendments highlights the ongoing struggle for religious freedom.

- Healing Ceremonies: Specific rituals led by spiritual healers or Medicine People to address physical, emotional, or spiritual imbalances, often involving songs, prayers, and the use of sacred objects and plants.

These are not mere rituals; they are embodied experiences that bring participants into direct relationship with the sacred, transforming individuals and strengthening communities.

Historical Trauma and Resurgence

The distinction between spirituality and religion is not merely academic; it is deeply rooted in the historical experience of Indigenous peoples. For centuries, colonial powers and later the U.S. government actively suppressed Native American spiritual practices, deeming them "pagan" or "savage." The forced assimilation policies, particularly through Indian boarding schools, aimed to "kill the Indian to save the man," systematically stripping children of their language, culture, and spiritual heritage.

Despite this concerted effort to eradicate Indigenous ways of life, Native American spirituality has shown remarkable resilience. The passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) in 1978, though imperfect, marked a significant step in recognizing and protecting Indigenous spiritual practices. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of traditional ways, with younger generations reclaiming their heritage, learning ancestral languages, and participating in ceremonies that were once driven underground. This revitalization is a testament to the enduring power and adaptability of Indigenous spirituality.

Avoiding Generalization and Appropriation

It is crucial to remember that "Native American spirituality" is not a monolithic entity. There are over 570 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone, each with unique languages, customs, and spiritual traditions. While common themes exist, the specific practices, stories, and beliefs vary widely. Generalizing all Indigenous spiritualities into one "religion" is a disservice to their diversity.

Furthermore, the growing interest in Native American spirituality has unfortunately led to widespread cultural appropriation by non-Native individuals and "New Age" movements. This often involves commodifying sacred ceremonies, misrepresenting traditional teachings, or claiming Indigenous spiritual authority without lineage, understanding, or respect for the closed nature of certain practices. True understanding requires deep respect, humility, and the recognition that these are living traditions belonging to specific peoples, not open for arbitrary adoption or commercial exploitation.

Conclusion

The distinction between Native American spirituality and Western religion is profound. It is not merely a semantic debate but a fundamental difference in worldview. While Western religions often focus on dogma, texts, and institutional structures, Native American spirituality is a holistic, living practice deeply rooted in interconnectedness, reciprocity, and an active, respectful relationship with the land, ancestors, and all living beings.

It is a way of life that has sustained Indigenous peoples through immense hardship and continues to offer profound wisdom for navigating the complexities of the modern world. To truly appreciate Native American spiritual traditions is to move beyond the narrow confines of "religion" and embrace a more expansive understanding of the sacred – one that is as diverse, dynamic, and enduring as the land itself. Recognizing this distinction is not just an act of intellectual clarity, but an essential step towards fostering respect, reconciliation, and genuine cross-cultural understanding.