The Enduring Heartbeat of Nations: Understanding Native American Tribal Self-Governance

In the intricate tapestry of the United States, a unique and often misunderstood form of sovereignty thrives: Native American tribal self-governance. Far from being mere enclaves or social programs, the 574 federally recognized tribal nations, along with numerous state-recognized and unrecognized tribes, exercise inherent governmental powers that predate the formation of the United States itself. This self-governance is not a privilege granted by Washington D.C., but an inherent right—a testament to the enduring heartbeat of distinct nations within a nation.

To truly grasp tribal self-governance, one must first shed the misconception that it is akin to state or local government. Instead, it is rooted in the concept of sovereignty, a fundamental principle that defines the relationship between tribes and the federal government. As Chief Justice John Marshall famously articulated in the 1832 Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia, Indian nations are "distinct, independent political communities, retaining their original natural rights." While their sovereignty has been diminished by centuries of colonial expansion and federal policy, it has never been extinguished.

A Journey Through Time: The Shifting Sands of Policy

The path to modern tribal self-governance is a tumultuous one, marked by cycles of recognition, suppression, and eventual resurgence.

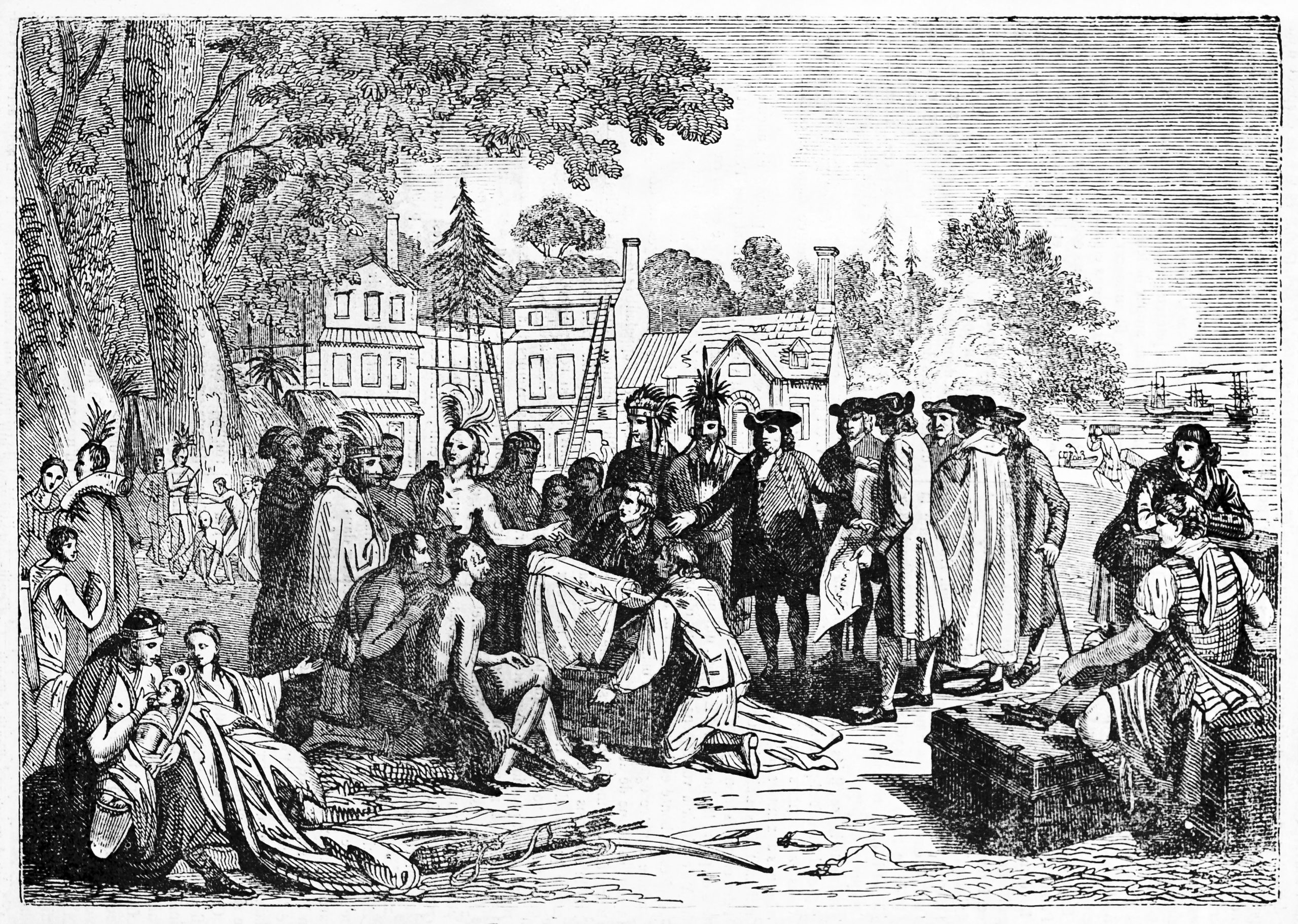

The Treaty Era (Pre-1871): In the early years of the United States, treaties were signed between the U.S. government and tribal nations, recognizing tribes as sovereign entities capable of negotiating agreements. Over 370 treaties were ratified, often involving land cessions in exchange for promises of protection, services, and the recognition of tribal homelands. This era firmly established the nation-to-nation relationship.

The Allotment and Assimilation Era (1887-1934): Driven by the belief that Native Americans needed to be "civilized" and integrated into mainstream society, policies like the Dawes Act of 1887 broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments. This era severely weakened tribal governments, eroded land bases, and sought to dismantle traditional cultures through boarding schools and other oppressive measures. It was a concerted effort to extinguish tribal sovereignty.

The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) (1934): A turning point, the IRA marked a shift away from assimilation. It encouraged tribes to adopt written constitutions and re-establish their governmental structures. While seen by some as an imposition of Western governance models, it provided a legal framework for tribes to rebuild and exercise some degree of self-rule.

The Termination Era (1953-1968): This was arguably the most devastating period for tribal sovereignty. Congress, fueled by a desire to "free" Native Americans from federal supervision and reduce federal expenditures, enacted policies to terminate the federal recognition of tribes, ending their sovereign status and trust relationships with the U.S. government. Over 100 tribes were terminated, leading to immense economic hardship, loss of land, and cultural disintegration. The Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin, for example, saw their successful timber industry collapse after termination, leading to widespread poverty and health crises.

The Self-Determination Era (1970-Present): The tide turned decisively in 1970 when President Richard Nixon delivered a landmark speech rejecting termination and calling for a new era of "self-determination without termination." He stated, "The time has come to break decisively with the past and to create the conditions for a new era in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions." This philosophy was codified in the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (ISDEAA), which allowed tribes to contract with the federal government to administer their own programs and services, rather than relying solely on federal agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). This act was a monumental step, empowering tribes to take control of their own destinies.

The Pillars of Self-Governance Today

Today, tribal self-governance is a vibrant, evolving reality, manifesting in diverse ways across Indian Country.

1. Governmental Structures:

Tribal governments operate much like any other sovereign government, with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. They adopt constitutions, elect leaders (presidents, chairpersons, councils), and enact laws. These governments manage everything from budgeting and land use to social services and infrastructure development. The specific structure varies widely; some tribes have traditional hereditary leadership, others have elected councils, and many blend traditional practices with modern governance models.

2. Tribal Justice Systems:

A cornerstone of sovereignty, tribal courts administer justice within their jurisdictions. They handle civil cases, family law, and criminal matters involving tribal members. However, their criminal jurisdiction over non-Native individuals on tribal lands was severely limited by the 1978 Supreme Court ruling in Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe. This ruling created a "jurisdictional void" where tribes could not prosecute non-Natives who committed crimes on their reservations, leading to significant public safety challenges, particularly in cases of domestic violence and sexual assault. Recent legislative efforts like the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) have sought to restore some of this jurisdiction, but the issue remains complex and contentious.

3. Economic Development:

Self-governance has been a powerful engine for economic growth. While gaming enterprises (casinos) are the most visible aspect, generating an estimated $39 billion annually and supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs, tribes are increasingly diversifying their economies. This includes energy development (oil, gas, solar, wind), agriculture, tourism, manufacturing, and technology. The ability to create their own regulatory frameworks and pursue ventures that align with their community values has allowed many tribes to lift their members out of poverty and invest in critical infrastructure and services.

4. Healthcare and Education:

Under ISDEAA, many tribes have taken over the administration of healthcare services previously provided by the Indian Health Service (IHS). This allows for culturally relevant care tailored to the specific needs of their communities. Similarly, tribes operate their own schools, colleges, and universities, often incorporating language immersion programs and traditional knowledge into their curricula, vital for cultural preservation. The Salish Kootenai College in Montana, for example, is tribally chartered and focused on serving the educational needs of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

5. Environmental Protection and Natural Resource Management:

Tribal nations often hold deep ancestral connections to their lands and waters. They exercise their sovereign authority to develop and enforce environmental regulations that can be more stringent than federal or state standards. They manage vast natural resources, from timber and fisheries to water rights and mineral extraction, often balancing economic development with traditional ecological knowledge and conservation.

Challenges and Nuances

Despite the progress, tribal self-governance faces persistent challenges:

- Underfunding: While tribes can contract for federal programs, the funding appropriated by Congress is often insufficient to meet the needs of their communities, particularly in areas like healthcare and infrastructure.

- Jurisdictional Complexities: The checkerboard ownership of land on many reservations, combined with the Oliphant ruling and recent Supreme Court decisions like Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta (2022), creates ongoing legal battles over who has authority to govern specific lands and people.

- External Pressures: State and local governments sometimes challenge tribal authority, particularly concerning taxation, gaming, and land use.

- Capacity Building: Many tribes, especially smaller ones, struggle with limited resources and human capital to fully exercise their governmental functions.

- Internal Divisions: Like any government, tribal governments can face internal political disputes, resource allocation challenges, and debates over traditional vs. modern governance.

The Enduring Legacy and Future

The exercise of self-governance has had profound positive impacts. It has led to significant improvements in health outcomes, educational attainment, and economic stability for many tribal communities. Crucially, it has enabled the revitalization of Native languages, cultures, and spiritual practices that were nearly eradicated. Tribes are increasingly asserting their voices on the national and international stage, advocating for their rights and sharing their unique perspectives on issues ranging from climate change to human rights.

The journey of Native American tribal self-governance is a testament to resilience, determination, and the enduring power of distinct cultural identities. It is a living, breathing example of diverse political systems coexisting within a larger nation. Understanding it requires acknowledging a complex history, appreciating the legal and practical realities of tribal sovereignty, and recognizing the inherent right of Indigenous peoples to define their own futures on their own terms. As nations within a nation, tribal governments are not just a part of America’s past; they are a vital, dynamic force shaping its present and future.