The Unfinished Ballot: A Centuries-Long Fight for Native American Voting Rights

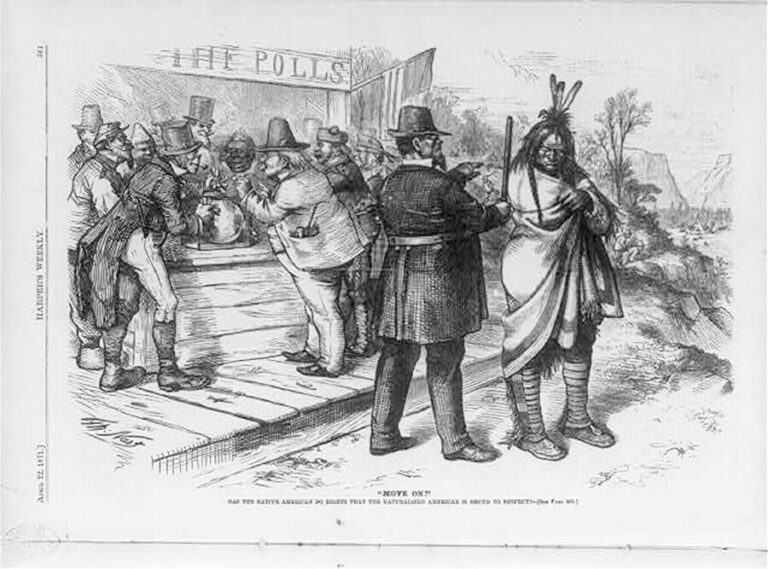

The right to cast a ballot is often hailed as the cornerstone of American democracy, a fundamental expression of citizenship. Yet, for the Indigenous peoples who walked these lands long before the concept of "America" existed, the path to the polling booth has been an arduous, centuries-long struggle, marked by legal battles, systemic disenfranchisement, and profound paradoxes. Their journey from sovereign nations to "wards of the state" and eventually, in theory, full citizens, reveals a voting rights history distinct from any other group, etched with resilience and an ongoing fight for equitable access to the democratic process.

For much of early American history, Native Americans were not considered citizens of the United States. Instead, they were often viewed as members of independent domestic dependent nations, a legal status articulated by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall in the 1830s. This classification, while acknowledging a form of sovereignty, simultaneously denied them the fundamental rights afforded to U.S. citizens, including the right to vote. Many states explicitly barred Native Americans from voting, often citing their unique tribal affiliations, their status as "non-taxed Indians," or their residency on reservations, which were seen as outside state jurisdiction.

The Dawes Act of 1887, a landmark piece of legislation aimed at assimilating Native Americans by breaking up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, offered a limited path to citizenship. Those who accepted allotments and severed ties with their tribes could, in some cases, become citizens and thus gain the right to vote. However, this was a coercive measure designed to dismantle tribal structures, and its impact on voting rights was piecemeal and often negligible. The vast majority of Native Americans remained outside the franchise.

The pivotal moment arrived with the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, also known as the Snyder Act. Passed in part as recognition for the thousands of Native Americans who served with distinction in World War I, the Act declared: "all noncitizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided, That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property."

While seemingly a sweeping victory, the 1924 Act was far from a universal enfranchisement. Crucially, the Constitution grants states the power to set voter qualifications. Many states, particularly in the West and Southwest with significant Native American populations, swiftly erected new barriers. Tactics included:

- Literacy Tests: These tests, often administered in English, were a formidable obstacle for communities where English was not the primary language, or where access to formal education had been denied.

- Poll Taxes: While less common for Native Americans than for African Americans, these economic barriers could still disenfranchise impoverished communities.

- Residency Requirements: States argued that Native Americans living on reservations were not residents of the state, or that they were "wards of the federal government" and thus ineligible to vote in state elections.

- "Competency" Clauses: Some states required Native Americans to prove their "competency" or demonstrate that they had abandoned tribal customs to be eligible to vote, a highly subjective and discriminatory standard.

- Intimidation and Violence: Overt threats, physical violence, and economic coercion were also employed to discourage Native Americans from registering or voting.

Arizona and New Mexico serve as stark examples of this post-1924 resistance. In Arizona, a 1928 state Supreme Court ruling, Porter v. Hall, declared that Native Americans were "wards of the government" and therefore not subject to the state’s election laws. This effectively disenfranchised most of the state’s Indigenous population. It wasn’t until 1948, in the landmark case of Harrison v. Laveen, that the Arizona Supreme Court finally struck down this discriminatory barrier, ruling that Native Americans had the right to vote. The plaintiffs, Frank Harrison and Harry Austin, both members of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, had courageously challenged the state’s registrar who refused to register them.

Similarly, New Mexico, despite having the largest Native American population at the time, also denied its Indigenous residents the right to vote. The state constitution included a provision disenfranchising "Indians not taxed," a clause that lingered until 1948 when it was challenged in Trujillo v. Garley. Miguel Trujillo, a decorated Marine Corps veteran and Isleta Pueblo member, sued the county clerk who refused his voter registration. The federal court ruled in his favor, asserting that the state’s argument that tribal members were "not taxed" was fallacious, as they paid various forms of taxes.

These 1948 rulings were significant victories, but the fight was far from over. Other states continued to suppress Native American votes well into the 1950s and even 1960s. Utah, for instance, did not fully remove its discriminatory voting barriers until 1957. Maine, despite its small Native American population, also maintained strict residency requirements that effectively disenfranchised tribal members living on reservations until a federal court order in 1954.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), a monumental achievement of the Civil Rights Movement, primarily targeted racial discrimination against African Americans in the South. While it provided some indirect benefits to Native Americans by outlawing literacy tests and poll taxes nationwide, its initial impact on Indigenous communities was less direct due to the specific nature of their disenfranchisement.

However, the 1975 Amendments to the VRA proved transformative for Native American voting rights. These amendments included vital provisions that recognized the unique linguistic and cultural barriers faced by Indigenous voters:

- Mandatory Language Assistance: Jurisdictions with significant language minority populations (including Native American languages) were required to provide bilingual ballots, voting instructions, and assistance. This was a game-changer for many tribal communities.

- Federal Oversight: The VRA allowed for federal examiners and observers to monitor elections in areas with a history of discrimination, providing a crucial check against local abuses.

The post-1975 era saw a significant increase in Native American voter registration and participation, as well as the emergence of powerful advocacy groups like the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), which has been at the forefront of litigation to protect and expand Indigenous voting rights.

Despite these legislative and legal victories, contemporary challenges persist, reflecting an evolving landscape of disenfranchisement tactics:

- Voter ID Laws: Strict photo ID laws disproportionately affect Native Americans, many of whom may lack state-issued IDs, have tribal IDs not recognized by the state, or live in remote areas without easy access to DMV services. The issue of street addresses versus P.O. boxes is particularly acute. Many reservation homes do not have traditional street addresses, relying instead on P.O. boxes. Yet, some states require a physical address for voter registration or ID purposes, effectively disenfranchising those without one.

- Polling Place Access: On vast reservations, polling places can be hundreds of miles apart, requiring extensive travel for voters who may lack reliable transportation. Reductions in polling sites or early voting locations further exacerbate this issue.

- Gerrymandering: Manipulating electoral district boundaries can dilute the Native American vote, reducing their political influence and ability to elect candidates of their choice.

- Voter Roll Purges: Aggressive voter roll maintenance efforts can inadvertently remove eligible Native American voters, especially if their names are common or if they have non-traditional addresses.

- Disinformation and Misinformation: Targeted campaigns to spread false information about voting procedures or eligibility can confuse and deter Native American voters.

- Continued Language Barriers: Even with VRA protections, the availability of culturally competent language assistance remains a challenge in many areas.

In recent years, Native American voters have become an increasingly recognized and potent political force, particularly in swing states like Arizona, Nevada, and North Carolina. Their turnout can be decisive in close elections, leading to increased efforts by political parties to engage with tribal communities. This growing political power has also led to more Native Americans running for and winning public office, bringing Indigenous voices and perspectives to legislative bodies at all levels.

The history of Native American voting rights is a testament to the enduring struggle for equality and self-determination. From being denied citizenship and deemed "wards" to battling discriminatory state laws and navigating modern barriers, Indigenous peoples have consistently fought to exercise their fundamental right to participate in the democratic process. While significant progress has been made, the ballot box remains, in many ways, an unfinished project – a symbol of both hard-won victories and the continuing imperative to ensure that the voices of America’s first peoples are fully heard and counted. The fight for true, equitable access to the ballot continues, driven by the unwavering belief that democracy is strongest when all its citizens, including its original inhabitants, can fully participate.