Echoes from the Tidewater: Unearthing the Complex History of the Powhatan Confederacy

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Pen Name]

Before the sails of European ships dotted the horizon, and long before the brick foundations of Jamestown rose from the Virginia marshlands, a sophisticated and powerful indigenous society thrived along the rivers and estuaries of what is now the American Mid-Atlantic. This was the world of the Powhatan Confederacy, a dynamic political and cultural entity that would become the first major Native American power to confront English colonialism in North America. Their story, often overshadowed by colonial narratives, is one of strategic leadership, fierce resistance, tragic decline, and enduring resilience.

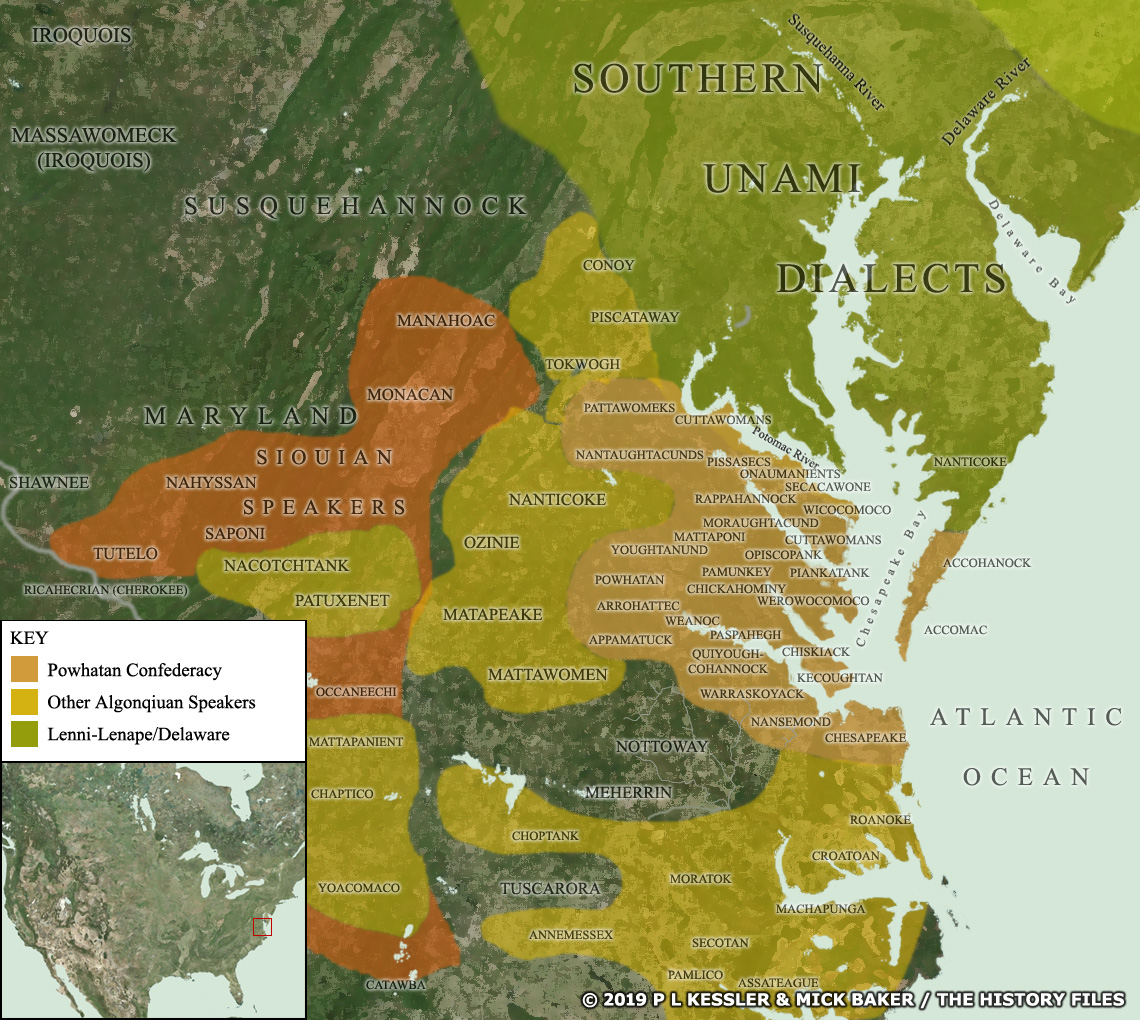

The Powhatan Confederacy was not a monolithic "nation" in the European sense, but rather a paramount chiefdom, a collection of some 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes bound together under the rule of a formidable paramount chief, or Mamanatowick. At the zenith of its power, this leader was Wahunsenacawh, famously known to the English as Chief Powhatan. His domain stretched across a vast swathe of present-day eastern Virginia, from the Potomac River in the north to the James River in the south, and west to the fall line, encompassing an estimated 13,000 to 21,000 people.

A Unified Domain: The Rise of Wahunsenacawh

Wahunsenacawh inherited the chieftainship of six tribes around 1570, but through a combination of strategic alliances, diplomacy, and conquest, he expanded his influence dramatically over the next few decades. His capital, Werowocomoco, was strategically located on the north bank of the York River, a powerful symbol of his authority. Each constituent tribe, led by its own weroance (chief), paid tribute to Powhatan in the form of corn, furs, copper, and other goods, solidifying a complex economic and political network.

The Powhatan people were expert farmers, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, which formed the bedrock of their diet. They were also skilled hunters, fishers, and gatherers, intimately connected to the rich natural resources of their environment. Their villages, often palisaded for defense, were permanent settlements, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of land management and resource sustainability. Their spiritual beliefs were deeply intertwined with the natural world, guided by priests and a reverence for powerful deities.

This well-established world was abruptly altered in May 1607, when three English ships, the Susan Constant, the Godspeed, and the Discovery, landed at what they named Jamestown. The arrival of the English marked the beginning of a profound and often violent clash of cultures, worldviews, and ambitions.

The Clash of Worlds: Jamestown’s Arrival

Initial interactions between the Powhatan and the English were a mix of curiosity, cautious trade, and immediate conflict. The English, driven by a desire for gold, land, and a passage to the Pacific, viewed the indigenous inhabitants as obstacles or potential laborers. The Powhatan, for their part, saw the English as strange, often vulnerable, newcomers who could potentially be integrated into their existing tributary system, or, if necessary, driven out.

Captain John Smith, a prominent figure in the early Jamestown settlement, became a central, albeit controversial, chronicler of these encounters. His accounts, often embellished for dramatic effect, shaped much of the popular understanding of Powhatan society. One of the most famous episodes, Smith’s supposed rescue by Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan’s daughter, has been widely romanticized. Historians largely agree that this event, if it happened, was likely a ritual adoption or a symbolic gesture of Powhatan’s power over Smith, rather than a genuine near-execution followed by a spontaneous act of mercy.

As Smith himself wrote, "They are in their hearts cruel, and more desirous of revenge than any thing under heaven." This quote, while reflecting colonial bias, also hints at the deep mistrust that quickly festered between the two groups. The English, often starving and ill-equipped, frequently raided Powhatan villages for food, escalating tensions.

The Anglo-Powhatan Wars: A Century of Conflict

The relationship quickly devolved into open warfare. The First Anglo-Powhatan War (1610-1614) erupted as the English, bolstered by new supplies and a more aggressive stance under Governor Lord De La Warr, launched brutal attacks on Powhatan villages. The war was characterized by scorched-earth tactics, crop destruction, and retaliatory raids.

A brief period of peace followed the war, largely due to the marriage of Pocahontas (renamed Rebecca upon her conversion to Christianity) to English colonist John Rolfe in 1614. This union, often portrayed as a symbol of harmony, was primarily a political alliance, intended to secure peace and facilitate trade. Pocahontas’s subsequent trip to England, where she was presented as a "civilized" native, further highlights the colonial desire to assimilate or control indigenous populations. Her untimely death in England in 1617, likely from disease, removed a crucial bridge between the two cultures.

The fragile peace shattered in 1622 with the Great Massacre, an coordinated uprising led by Opechancanough, Wahunsenacawh’s younger brother and successor, who deeply distrusted the English. On March 22, 1622, Powhatan warriors launched a surprise attack on English settlements, killing nearly a third of the colonial population – approximately 347 people. This devastating blow was a desperate attempt to drive the English from their lands, but it ultimately backfired.

The English retaliated with merciless force. The Second Anglo-Powhatan War (1622-1632) became a war of attrition, marked by systematic campaigns of destruction against Powhatan villages, crops, and people. The English adopted a policy of extermination and displacement, viewing the uprising as justification for their violent expansion. Disease, to which Native Americans had no immunity, also continued to decimate the Powhatan population, weakening their ability to resist.

Decline and Dispossession: The Last Stand

Despite the mounting losses, Opechancanough, remarkably resilient and still fiercely independent in his 90s, launched one final, desperate offensive in 1644. The Third Anglo-Powhatan War (1644-1646) saw Powhatan warriors again attack English settlements, killing hundreds. However, the English colonial population had grown significantly, and their military superiority was now overwhelming.

Opechancanough was captured and brutally murdered by an English guard while imprisoned in Jamestown in 1646. His death effectively marked the end of the Powhatan Confederacy as an independent political and military power. The subsequent Treaty of 1646 forced the remaining Powhatan tribes into tributary status, requiring them to pay an annual tribute to the English governor and confining them to designated reservations. They were forbidden from entering English-controlled lands without permission, a stark symbol of their lost sovereignty.

Over the ensuing decades, the remaining Powhatan people faced relentless pressure. Land encroachment, further disease outbreaks, forced assimilation, and intermarriage with both English settlers and enslaved Africans led to a significant decline in their distinct cultural identity and population numbers. Many Powhatan descendants were pushed further into the margins of colonial society, often losing their ancestral lands and traditional ways of life.

An Enduring Legacy: Resilience and Revival

The story of the Powhatan Confederacy is not merely one of decline, but of enduring resilience. Despite centuries of oppression, their descendants have survived and thrived. Today, several federally and state-recognized tribes in Virginia proudly trace their lineage back to the Powhatan Confederacy, including the Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Nansemond, and Rappahannock.

These modern tribes are actively engaged in cultural revitalization efforts, working to preserve their languages, traditions, and historical narratives. They operate museums, conduct archaeological research, and advocate for their rights, ensuring that the legacy of Wahunsenacawh, Opechancanough, and the vibrant Powhatan people is not forgotten.

The history of the Powhatan Confederacy serves as a powerful reminder of the profound impact of European colonization on indigenous societies. It highlights the courage and strategic brilliance of Native American leaders, the devastating consequences of disease and warfare, and the enduring spirit of a people who, against overwhelming odds, have maintained their connection to their ancestral lands and identity. Their echoes resonate through the tidewater, a testament to a rich past and a determined future.