Echoes from an Ancient Continent: Unveiling Pre-Columbian Native American History

Before the sails of Christopher Columbus breached the horizon in 1492, signalling the dawn of European contact, the Americas were far from an empty wilderness. They were a vibrant tapestry woven over millennia, home to tens of millions of people living in complex, dynamic, and astonishingly diverse societies. From the frozen reaches of the Arctic to the dense Amazonian rainforests and the towering peaks of the Andes, indigenous peoples had shaped sophisticated civilizations, developed intricate knowledge systems, and engineered monumental feats of architecture and agriculture. This rich, expansive narrative is what we call Pre-Columbian Native American history – a story of ingenuity, resilience, and profound human achievement often overshadowed by the narratives of conquest that followed.

To truly grasp the magnitude of Pre-Columbian history, we must first dispel the myth of the "New World" as a pristine, uninhabited land awaiting discovery. Archaeological evidence, oral traditions, and re-evaluated historical accounts reveal a continent teeming with life, where cities rivalled those of Europe in size and sophistication, and intricate trade networks spanned vast distances.

The Deep Roots: From Ice Age Migrations to the Archaic Bloom

The earliest chapters of this history begin not with cities, but with migrations. While debates continue about the precise timing and routes, the prevailing theory posits that the first humans arrived in the Americas from Asia, likely via a land bridge across the Bering Strait (Beringia) during the last Ice Age, perhaps as early as 15,000 to 20,000 years ago, if not earlier, as recent discoveries like the Monte Verde site in Chile suggest. These Paleo-Indians, adept hunters and gatherers, followed megafauna like mammoths and mastodons, gradually populating the two vast continents.

The "Clovis culture," identified by distinctive fluted projectile points, was long considered the earliest widespread culture in North America, dating back around 13,000 years ago. However, discoveries at sites like Paisley Caves in Oregon, with human DNA dating to 14,300 years ago, challenge the "Clovis First" paradigm, indicating a more complex and possibly earlier peopling of the Americas.

As the Ice Age ended and the climate warmed, around 8,000 BCE, the megafauna disappeared, ushering in the Archaic period. This era was characterized by increasing regional diversity and adaptation. People developed specialized hunting tools for smaller game, expanded their use of wild plants, and began to exploit aquatic resources. Semi-permanent settlements emerged, particularly in resource-rich areas, laying the groundwork for the agricultural revolution that would transform societies across the Americas.

The Agricultural Revolution: Seeds of Civilization

Just as in the Fertile Crescent, the development of agriculture in the Americas was a pivotal turning point. Unlike the Old World, where wheat and barley dominated, the Americas saw the domestication of unique crops. Maize (corn) stands as the most significant, first cultivated in Mesoamerica around 9,000 years ago. Its domestication from wild teosinte grass was a remarkable feat of genetic engineering by early farmers. Along with beans and squash, these "Three Sisters" formed a nutritional powerhouse, providing a stable food supply that supported exponential population growth and the development of sedentary lifestyles.

The agricultural surplus freed people from constant foraging, allowing for specialization of labor, the accumulation of wealth, and the emergence of social hierarchies. This agricultural revolution laid the foundation for the complex chiefdoms, city-states, and empires that would define the later Pre-Columbian periods.

North America’s Diverse Tapestry: From Mounds to Cliff Dwellings

While often overshadowed by the grandeur of Mesoamerican and Andean empires, Pre-Columbian North America was home to a staggering array of cultures, each uniquely adapted to its environment.

In the Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to by the Navajo term "Anasazi," meaning "ancient enemies," though "Ancestral Puebloans" is preferred) flourished from roughly 200 to 1300 CE. Known for their intricate multi-story cliff dwellings at sites like Mesa Verde and their massive planned communities at Chaco Canyon, they were master architects and engineers. Pueblo Bonito at Chaco Canyon, for instance, contained over 600 rooms and was a major cultural and trade center, featuring sophisticated astronomical alignments. The Hohokam, another Southwestern culture, developed extensive irrigation canals, some stretching for miles, to farm the arid desert.

Further east, in the Midwest and Southeast, the "Mound Builders" left an indelible mark. This tradition spans millennia, beginning with the Adena and Hopewell cultures (c. 1000 BCE – 500 CE), known for their elaborate burial mounds, effigy mounds (like the Great Serpent Mound), and extensive trade networks that brought exotic materials from across the continent. The Mississippian culture, flourishing from about 800 to 1600 CE, represented the pinnacle of this tradition. Their largest urban center, Cahokia, located near modern-day St. Louis, was a sprawling city with an estimated population of 10,000-20,000 people at its peak around 1050 CE – larger than London at the time. Its central feature, Monks Mound, is the largest earthen structure in North America, a testament to immense organized labor and a complex social structure. Cahokia was a major hub for trade, politics, and religious life, with a clear social hierarchy evident in its layout and burial practices.

In the Northeast Woodlands, groups like the Iroquois Confederacy, formed possibly as early as the 12th century, created a sophisticated political and social system. The "Great Law of Peace" united five (later six) nations into a powerful league, influencing European colonists with its concepts of democratic governance and checks and balances, potentially even inspiring aspects of the U.S. Constitution. They lived in longhouses, practiced extensive agriculture, and engaged in both warfare and diplomacy.

Along the Pacific Northwest coast, rich marine resources allowed for the development of complex, hierarchical societies without reliance on agriculture. Groups like the Kwakwaka’wakw and Haida were renowned for their monumental totem poles, intricate wood carving, and the elaborate "potlatch" ceremonies – feasts and gift-giving rituals used to redistribute wealth and affirm social status.

Mesoamerican Grandeur: Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan, and Aztec

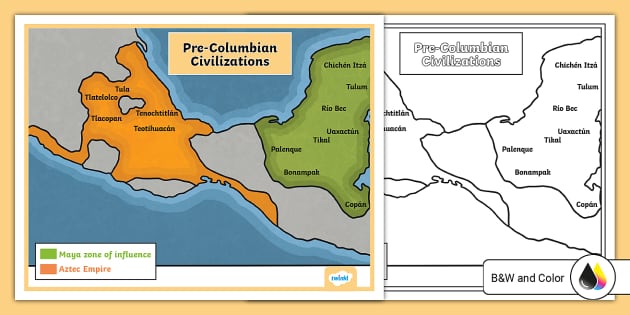

Mesoamerica, encompassing parts of modern-day Mexico and Central America, was a cradle of civilization.

The Olmec (c. 1500-400 BCE) are often considered the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica. They laid the groundwork for later civilizations, developing monumental stone sculpture (including colossal heads), early writing systems, a complex calendar, and ritual ballgames. Their influence spread widely through trade and cultural exchange.

Following the Olmec, the Maya civilization blossomed (c. 250-900 CE, though extending before and after this Classic period). Spread across southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, the Maya were not a unified empire but a network of independent city-states like Tikal, Palenque, and Copán. They achieved astonishing intellectual feats: a sophisticated hieroglyphic writing system, advanced mathematics (including the concept of zero), and incredibly accurate astronomical observations that led to complex calendar systems, including the Long Count. Their cities featured towering pyramids, elaborate palaces, and intricate relief carvings. While the Classic Maya experienced a decline in the southern lowlands around 900 CE (a "collapse" whose causes are still debated), Maya culture continued to thrive in other regions, adapting and evolving until the arrival of the Spanish.

Contemporaneous with the Classic Maya, the city of Teotihuacan (c. 100-600 CE) dominated the central Mexican highlands. With an estimated population of 125,000-200,000, it was one of the largest cities in the world at its peak. Its monumental structures, like the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, were built along a precise grid plan, indicating advanced urban planning and a powerful, centralized authority. Though its ruling class remains enigmatic, Teotihuacan’s cultural and economic influence radiated throughout Mesoamerica.

The last great Mesoamerican empire before the Spanish arrived was the Aztec (c. 1345-1521 CE). Emerging from humble beginnings as nomadic Chichimec people, they built their magnificent capital, Tenochtitlan, on an island in Lake Texcoco (modern-day Mexico City). With a population estimated at 200,000-300,000, Tenochtitlan was a marvel of urban planning, featuring vast temples, palaces, and a sophisticated system of chinampas (floating gardens) that fed its massive populace. The Aztec created a vast tributary empire through military conquest, demanding tribute from conquered peoples across central Mexico, cementing their control over a powerful economic and political network.

Andean Empires and Innovations: From Caral to Inca

South America’s Andean region, characterized by its dramatic mountains, arid coasts, and fertile valleys, also fostered a succession of remarkable civilizations.

One of the earliest known civilizations in the Americas emerged along the Peruvian coast: the Norte Chico civilization (also known as Caral-Supe), dating back to around 3000 BCE. Contemporaneous with the pyramids of Egypt, their monumental pyramids and complex urban centers like Caral demonstrate early forms of organized labor and sophisticated social structures, remarkably without evidence of pottery or extensive warfare.

Later cultures like the Chavín (c. 900-200 BCE) spread a unified religious iconography across the highlands and coast. The Moche (c. 100-800 CE) on the northern coast were renowned for their elaborate pottery, intricate metallurgy, and massive adobe huacas (pyramids). The Nazca (c. 100-800 CE), further south, are famous for the enigmatic Nazca Lines – vast geoglyphs etched into the desert floor, whose purpose remains a subject of intense debate.

The Tiwanaku (c. 500-1000 CE), based near Lake Titicaca in modern-day Bolivia, developed sophisticated agricultural techniques for high-altitude farming, including raised fields, and exerted considerable influence over a vast region. The Wari (c. 600-1000 CE), based in the central highlands of Peru, built an empire with extensive road systems and administrative centers, laying some groundwork for the later Inca.

The culmination of Andean civilization was the Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu), which flourished from the early 15th century until the Spanish conquest in 1532. Originating in the Cusco Valley, the Inca rapidly expanded, creating the largest empire in Pre-Columbian America, stretching over 2,500 miles along the spine of the Andes. They achieved this feat without a written language (using the quipu, a system of knotted cords, for record-keeping), the wheel, or iron tools. Their achievements were astounding: a vast network of some 25,000 miles of paved roads and suspension bridges, sophisticated terraced agriculture, monumental stone architecture (epitomized by Machu Picchu), and a highly centralized, efficient administration that redistributed resources and managed a diverse population of millions.

A Legacy Reclaimed

Pre-Columbian Native American history is not a static, singular narrative but a kaleidoscope of human experience. It is a story of profound adaptability to diverse environments, of intricate spiritual beliefs, of remarkable artistic expression, and of complex social and political structures that challenge simplistic notions of "primitive" societies. These were dynamic civilizations, constantly evolving, trading, warring, and innovating.

The arrival of Europeans brought catastrophic changes – disease, violence, and forced assimilation – that decimated populations and disrupted ancient ways of life. Yet, the echoes of Pre-Columbian history resonate today. Indigenous languages, traditions, and knowledge systems persist, a testament to the enduring strength and resilience of Native American peoples.

Understanding this rich past is crucial. It helps us appreciate the full scope of human achievement, challenges colonial narratives that erased or minimized indigenous contributions, and fosters a deeper respect for the diverse cultural heritage of the Americas. Pre-Columbian history is not merely a prelude to European arrival; it is a monumental saga in its own right, one that continues to reveal its secrets and inspire awe with every new discovery.