Echoes of Resilience: A Journey Through Sac and Fox Nation History

The history of the Sac and Fox Nation is a profound testament to resilience, adaptation, and the enduring spirit of a people who have navigated centuries of immense change. From their ancestral homelands in the Great Lakes region to their forced removal across the Mississippi, and finally to their establishment in Oklahoma, the Sac and Fox (or Sauk and Meskwaki, as they are traditionally known) have maintained a distinct cultural identity despite overwhelming pressures. Their story is not just one of displacement and loss, but also of steadfast determination to preserve their heritage and sovereignty.

Origins and Early Alliances: "People of the Yellow Earth" and "People of the Outlet"

Before European contact, the Sac (Sauk, meaning "People of the Outlet" or "People of the Yellow Earth") and the Fox (Meskwaki, meaning "People of the Red Earth" or "People of the Yellow Earth") were distinct Algonquian-speaking tribes. The Sac originally inhabited areas around present-day Michigan and Wisconsin, while the Fox were concentrated in the Fox River valley in Wisconsin. Despite their separate identities, they formed a powerful and enduring alliance, often referred to collectively by Europeans as the "Sac and Fox." This alliance was forged out of necessity, as both tribes faced encroachment and conflict with other Indigenous nations and, increasingly, with European powers.

Their societies were highly organized, based on a balance of civil and war chiefs, clan systems, and a deep spiritual connection to the land. They were skilled hunters, farmers, and traders, thriving in the rich ecosystems of the Great Lakes. Their strategic location, controlling key waterways and trade routes, made them formidable players in the early fur trade with the French.

European Contact and the Shifting Sands of Power

The arrival of French traders in the 17th century marked a significant turning point. Initially, the Sac and Fox engaged in a complex relationship with the French, benefiting from access to European goods like firearms and tools. However, as French influence grew and other tribes became allied with them, the Sac and Fox found themselves in direct conflict. The brutal "Fox Wars" (early 18th century) against the French and their Indigenous allies nearly annihilated the Fox, driving the survivors to seek refuge among the Sac. This period solidified their alliance, binding their destinies together even more tightly.

As British power supplanted French, and later, American expansion began to dominate, the Sac and Fox found themselves caught in a geopolitical struggle. They shrewdly navigated these shifting alliances, often playing one power against another to protect their interests and lands. During the American Revolution and the War of 1812, many Sac and Fox warriors sided with the British, viewing them as a lesser threat to their sovereignty compared to the land-hungry American settlers. This decision would have profound consequences.

The Treaty of 1804 and the Seeds of Conflict

Perhaps no single event better illustrates the inherent tensions and misunderstandings between the Sac and Fox and the burgeoning United States than the Treaty of 1804. Negotiated in St. Louis, this treaty ceded a vast tract of land, encompassing much of present-day Illinois, Wisconsin, and Missouri, to the U.S. government for a mere $2,234.50 in goods and an annual annuity.

The controversy surrounding this treaty is immense. The Sac and Fox later argued that the delegation who signed it did not have the authority to cede such a large territory, nor did they fully comprehend the implications of the document. The signing occurred under questionable circumstances, with tribal leaders reportedly intoxicated. For the U.S., it was a legal acquisition; for the Sac and Fox, it was a profound betrayal and the root of future conflict. As historian R. David Edmunds notes, "The Treaty of 1804 became the touchstone of Sac and Fox grievances against the United States for the next three decades."

Black Hawk’s Stand: A Fight for Homeland

The 1804 treaty laid the groundwork for the most famous and tragic chapter in Sac and Fox history: the Black Hawk War of 1832. Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak), a respected Sac warrior and leader, vehemently opposed the treaty’s legitimacy. He represented a faction of the Sac and Fox who refused to abandon their ancestral village of Saukenuk, located at the confluence of the Rock and Mississippi Rivers in Illinois – land supposedly ceded in 1804.

While his rival, Keokuk, favored accommodation and relocation, Black Hawk believed in fighting for their right to remain on their land. In the spring of 1832, facing starvation and constant harassment from white settlers, Black Hawk led a "British Band" of about 1,000 Sac, Fox, and Kickapoo people, including women, children, and elders, back across the Mississippi into Illinois. His intention was not war, but to plant corn and reclaim their home.

However, the return was perceived as an invasion by American authorities. What followed was a brutal and largely one-sided conflict. The U.S. military, including future President Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, pursued Black Hawk’s band. The conflict culminated in the horrific "Bad Axe Massacre" in August 1832, where hundreds of Sac and Fox, attempting to cross the Mississippi to escape, were slaughtered by U.S. troops and their Sioux allies. Black Hawk himself was captured shortly after.

His famous surrender speech, though likely recorded and embellished by white observers, encapsulates the despair and defiance of his people: "I am a man and you are another… You say that you want to put me in prison; if you do, you will break my heart, and I shall die. I hope, therefore, that you will not be so hard as to put me in irons. I have always been a warrior; I have been in many battles, and have always fought for my people."

The Black Hawk War effectively ended organized Indigenous resistance in the Old Northwest and accelerated the forced removal of tribes west of the Mississippi.

The Long Exile: From Iowa to Kansas to Oklahoma

Following the Black Hawk War, the Sac and Fox were forced into a series of land cessions and removals. First, they were relocated to a reservation in Iowa. But the pressure for land continued. In 1842, they signed another treaty, ceding most of their Iowa lands and agreeing to move to a reservation in Kansas.

This period was marked by profound cultural disruption. Traditional ways of life were increasingly difficult to maintain. The bison herds were diminishing, and farming in new environments proved challenging. Disease, poverty, and internal divisions exacerbated their suffering.

Yet, even in Kansas, their tenure was short-lived. The westward expansion of American settlers continued unabated, and by the 1860s, the U.S. government was pushing for the removal of all tribes from Kansas to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). In 1867, the majority of the Sac and Fox were forced to relocate to a new reservation in what would become Lincoln and Pottawatomie counties in Oklahoma. A smaller group, however, resisted this final removal and managed to purchase a small parcel of land back in Iowa, where they established the Meskwaki Settlement, maintaining their distinct identity to this day.

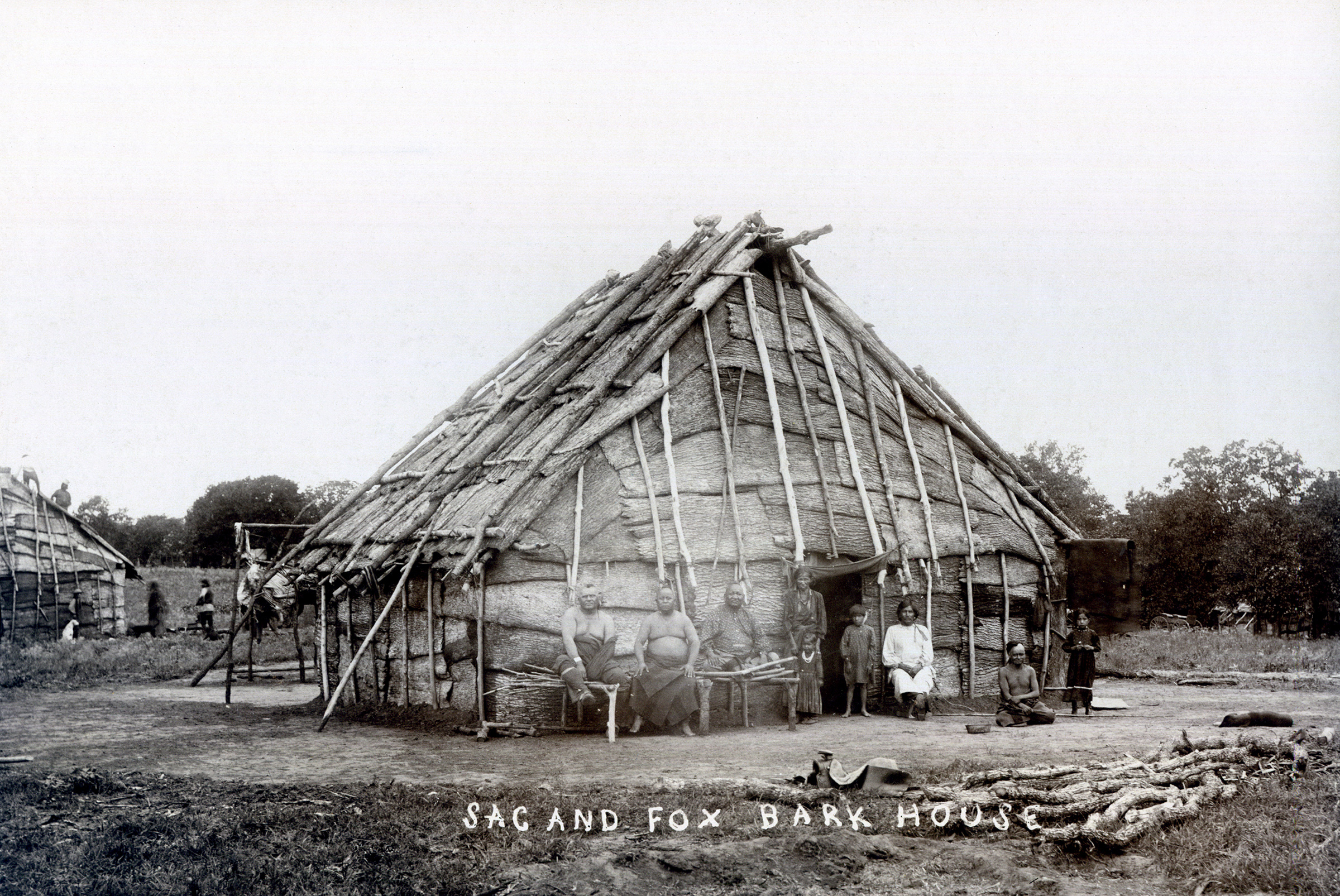

Life on the Oklahoma Reservation and the Allotment Era

The Sac and Fox in Oklahoma faced immense challenges. The new lands were different, and the U.S. government implemented policies designed to assimilate Native Americans. The Dawes Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act) was particularly devastating. It broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, often selling off "surplus" land to non-Native settlers. For the Sac and Fox, this resulted in a dramatic loss of land base and further eroded their traditional communal structures.

Children were sent to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their native languages or practice their cultural traditions. The goal was to "kill the Indian, save the man." Despite these pressures, many Sac and Fox families quietly resisted, passing down their language, stories, and ceremonies in secret.

Reorganization and Self-Determination: A New Dawn

The early 20th century brought renewed hope for tribal sovereignty. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, and specifically the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936, provided a framework for tribes to reestablish their tribal governments and regain some control over their affairs. The Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma formally adopted a constitution and bylaws, establishing a tribal business committee and later a tribal council, laying the groundwork for modern self-governance.

The late 20th century saw a dramatic shift towards self-determination. The Sac and Fox Nation, like many tribes, began to assert their sovereignty more forcefully, developing their own infrastructure, social programs, and economic ventures.

The Modern Sac and Fox Nation: Sovereignty, Culture, and Future

Today, the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma is a vibrant and forward-looking tribal government. Headquartered in Stroud, Oklahoma, the Nation is a federally recognized tribe with a strong commitment to its citizens and the preservation of its rich heritage.

Economic development has been key to their modern success. Like many tribes, gaming operations have provided a significant source of revenue, funding essential services such as healthcare, education, housing, and elder care programs. The Nation also operates other businesses, diversifying its economic base.

Cultural preservation is a paramount focus. Efforts are underway to revitalize the Sac and Fox languages (Sauk and Meskwaki), often through language immersion programs and documentation projects. Traditional ceremonies, dances, and arts are being taught to younger generations, ensuring the continuation of their unique identity. The Nation also maintains its own police department, courts, and health clinic, embodying the principles of self-governance and sovereignty that their ancestors fought so hard to protect.

The Sac and Fox Nation’s journey is a powerful reminder of the profound impact of colonialism and forced assimilation, but even more so, it is a testament to the enduring strength of Indigenous cultures. From the banks of the Mississippi to the plains of Oklahoma, the echoes of their ancestors’ resilience resonate in every step taken towards a sovereign and self-determined future. Their history is not merely a collection of past events but a living narrative that continues to shape their identity and guide their path forward.