The Unconquered Spirit: Florida’s Enduring Seminole Legacy

Florida, a land of sun-drenched beaches, sprawling theme parks, and bustling metropolises, holds within its history a narrative of defiance, resilience, and an unwavering spirit of independence. This is the story of the Seminole people, a unique and dynamic Native American tribe whose presence in the Sunshine State is not merely a historical footnote but a living, breathing testament to survival against overwhelming odds. Unlike most other Native American tribes in the United States, a significant portion of the Seminole people were never formally conquered, nor did they sign a peace treaty with the U.S. government. Their history in Florida is a saga of adaptation, fierce resistance, and remarkable resurgence.

To understand the Seminole, one must first appreciate their origins. They are not an ancient, indigenous tribe of Florida in the same way the Timucua or Calusa were. Instead, the Seminoles emerged in the 18th century as a composite people, forged in the crucible of migration and conflict. Their ancestors were primarily Muscogee (Creek) people who migrated south from Georgia and Alabama into the sparsely populated Florida peninsula, seeking new lands and escaping the pressures of American expansion. They were joined by remnants of earlier Florida tribes decimated by disease and warfare, as well as by a significant number of runaway slaves (often called Black Seminoles or Estelusti, "Black People").

This diverse melting pot of cultures, languages (Muscogee and Mikasuki), and experiences coalesced into a distinct identity. The name "Seminole" itself is believed to derive from the Muscogee word "simanó-li," meaning "runaway," "wild," or "unconquered," a fitting descriptor for a people who would soon face the full might of a burgeoning nation.

The Crucible of Conflict: The Seminole Wars

The early 19th century brought increasing friction between the Seminoles and the expanding American frontier. The Seminoles’ practice of offering sanctuary to runaway slaves, combined with American desires for their fertile lands, set the stage for one of the most brutal and prolonged conflicts in American history: the Seminole Wars.

The First Seminole War (1817-1818) was primarily a series of border skirmishes and punitive expeditions led by General Andrew Jackson. Jackson, exceeding his orders, invaded Spanish Florida, attacking Seminole towns and British traders whom he accused of aiding the Native Americans. This war highlighted the U.S. government’s determination to control Florida and its Native American inhabitants, even before the territory was officially acquired from Spain in 1819.

However, it was the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) that truly defined the Seminole struggle. This was the longest and most costly Indian war in U.S. history, both in terms of human lives and financial expenditure. Sparked by the U.S. government’s relentless efforts to remove the Seminoles to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Seminoles, led by charismatic figures like Osceola, Micanopy, and Abiaka (Sam Jones), refused to yield.

Osceola, though not a chief by hereditary right, rose to prominence through his eloquence and fierce opposition to removal. His defiant stance against American treachery became legendary. When presented with a treaty for removal, he famously plunged his knife into it, declaring, "The only treaty I will ever make with the white man is this!" His capture under a flag of truce in 1837, and subsequent death in captivity, became a symbol of American perfidy, further fueling Seminole resistance.

The Seminoles, masters of the Florida landscape, employed devastating guerrilla tactics. They ambushed U.S. troops in the dense cypress swamps and thick hammocks, launching surprise attacks like the Dade Massacre in December 1835, where over 100 U.S. soldiers were killed, igniting the full fury of the war. U.S. forces, numbering in the tens of thousands at their peak, struggled to locate and defeat the elusive Seminoles in the unforgiving Everglades terrain. It was a war of attrition, marked by disease, exhaustion, and frustration for the American military.

By the end of the Second Seminole War, thousands of Seminoles had been forcibly removed to the West. However, a small, determined band, estimated to be between 100 and 300 people, managed to elude capture. They retreated deep into the impenetrable fastness of the Everglades, finding refuge in its remote islands and cypress domes.

The Third Seminole War (1855-1858) was a final, smaller-scale attempt by the U.S. government to remove the remaining Seminoles. Led by figures like Billy Bowlegs, this conflict also proved largely inconclusive. The U.S. eventually abandoned its efforts, realizing the immense cost and futility of rooting out every last Seminole from their swampy strongholds. It was this small, resilient group that formed the nucleus of what would become today’s Seminole and Miccosukee tribes in Florida. They remained, defiantly, the "unconquered."

Life in the Everglades: Adaptation and Isolation

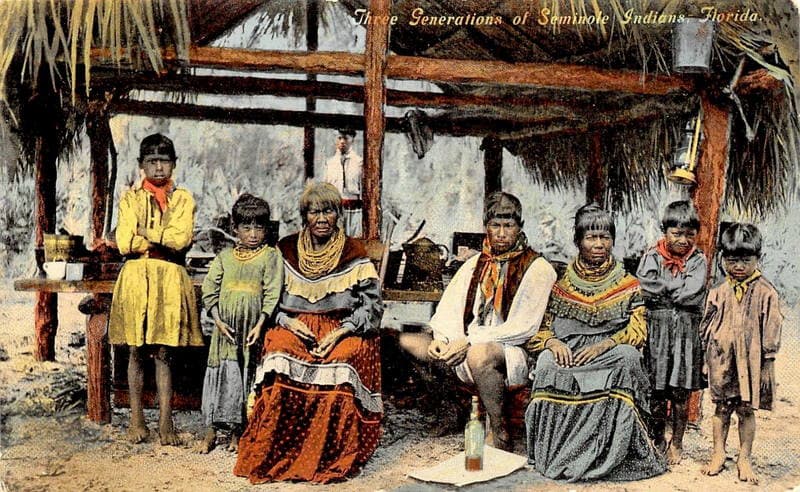

For decades after the wars, the surviving Seminoles lived in near-total isolation in the Everglades. They perfected their traditional ways of life, building chickee huts (open-sided, palmetto-thatched dwellings) raised on stilts to protect against water and insects. They hunted deer, alligators, and birds, fished in the abundant waters, and gathered wild plants. Their diet was supplemented by growing small plots of corn, pumpkins, and sweet potatoes.

Their culture continued to evolve, giving rise to the distinctive Seminole patchwork clothing, characterized by intricate designs of geometric shapes and vibrant colors, which became a powerful symbol of their identity. This period of isolation fostered a deep connection to the land and a fierce commitment to preserving their cultural heritage, languages, and spiritual practices, including the annual Green Corn Dance.

Emergence into the Modern World: Recognition and Resurgence

The early 20th century saw the Seminoles gradually emerge from their self-imposed isolation. Trade with non-Native Floridians increased, with Seminoles exchanging furs, alligator hides, and crafts for manufactured goods. The construction of the Tamiami Trail in the 1920s, cutting through the heart of the Everglades, brought both challenges and opportunities, leading to increased contact and some tourism.

A pivotal moment came in the mid-20th century. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which encouraged Native American tribes to establish self-governing bodies, the Florida Seminoles began to organize. In 1957, the Seminole Tribe of Florida officially gained federal recognition, establishing a tribal government and constitution. Later, in 1962, a separate group, primarily Mikasuki speakers, formed the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, also gaining federal recognition. These two federally recognized tribes represent the descendants of those who resisted removal.

The second half of the 20th century marked a period of remarkable economic and cultural resurgence. Initially, the Seminole Tribe focused on cattle ranching, citrus groves, and small-scale tourism ventures, including the popular alligator wrestling shows. However, the true game-changer arrived in 1979 when the Seminole Tribe of Florida opened the first tribally operated high-stakes bingo hall in the United States on their Hollywood Reservation. This groundbreaking move, initiated by then-tribal chairman James Billie, challenged state laws and ultimately led to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (1987), which affirmed tribal sovereignty over gaming on reservation lands.

This decision paved the way for the explosion of tribal gaming across the nation, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida became a pioneer and a powerhouse in the industry. Their gaming enterprises, particularly the globally recognized Hard Rock International brand (which they acquired in 2007, making them the first Native American tribe to own a major international hospitality company), have transformed their economic fortunes.

The Seminole Today: Sovereignty, Culture, and the Future

Today, the Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida are vibrant, sovereign nations within a nation. They operate sophisticated governments, manage diverse economic portfolios, and invest heavily in the well-being of their people. Modern Seminole life is a blend of tradition and modernity. While tribal members live in contemporary homes, attend schools, and pursue diverse careers, they also actively preserve their languages, ceremonies, and arts. The annual Brighton Field Day and Rodeo, the Immokalee Tribal Fair, and the Green Corn Dance are vital cultural events that connect generations to their heritage.

The Seminole Tribe of Florida maintains six reservations across the state (Brighton, Big Cypress, Hollywood, Immokalee, Fort Pierce, and Tampa), while the Miccosukee Tribe has a reservation west of Miami. Both tribes continue to advocate for their rights, protect their ancestral lands, and contribute significantly to Florida’s economy and cultural landscape.

The story of the Seminole people in Florida is more than just a historical account; it is a living testament to an enduring spirit. From their origins as a composite people to their fierce resistance in the Everglades, and finally to their modern-day status as economic powerhouses and cultural beacons, the Seminoles embody the true meaning of "unconquered." Their journey serves as a powerful reminder that history is not just about what was lost, but also about what was preserved, adapted, and ultimately, triumphed. As one Seminole elder once put it, "We are still here. We never left. And we are still strong." This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the enduring legacy of Florida’s Seminole people.