The Silent Revolution: How the Cherokee Syllabary Transformed a Nation

In the annals of human ingenuity, few stories resonate with the quiet power and profound impact as that of the Cherokee Syllabary. More than just a writing system, it was a revolution – a singular act of intellectual prowess that, in a remarkably short span, pulled a vibrant Indigenous nation into the modern era of literacy, empowering its people, solidifying its identity, and allowing its voice to echo across generations, even in the face of unimaginable adversity.

At its heart lies the figure of Sequoyah, a man of extraordinary vision and perseverance. Born around 1770 in Tuskegee, Tennessee, to a Cherokee mother and a white father, Sequoyah (whose English name was George Gist or Guess) grew up immersed in Cherokee culture and language. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he never learned to read or write English. Yet, he was keenly aware of the power that written communication afforded the white settlers – the ability to record history, conduct business, disseminate laws, and exchange ideas across vast distances. He saw his own people, with their rich oral tradition, at a distinct disadvantage in a rapidly changing world.

The Genesis of an Idea

The idea that consumed Sequoyah for over a decade was audacious: to create a writing system for the Cherokee language. It was a pursuit that baffled and even angered many in his community, who saw it as a strange obsession, a fruitless endeavor. He experimented with various methods, initially trying to create a character for every word, a task he quickly realized was insurmountable given the thousands of words in the Cherokee lexicon. He then considered adapting the English alphabet, but that too proved inadequate; the sounds of Cherokee simply did not map neatly onto English letters.

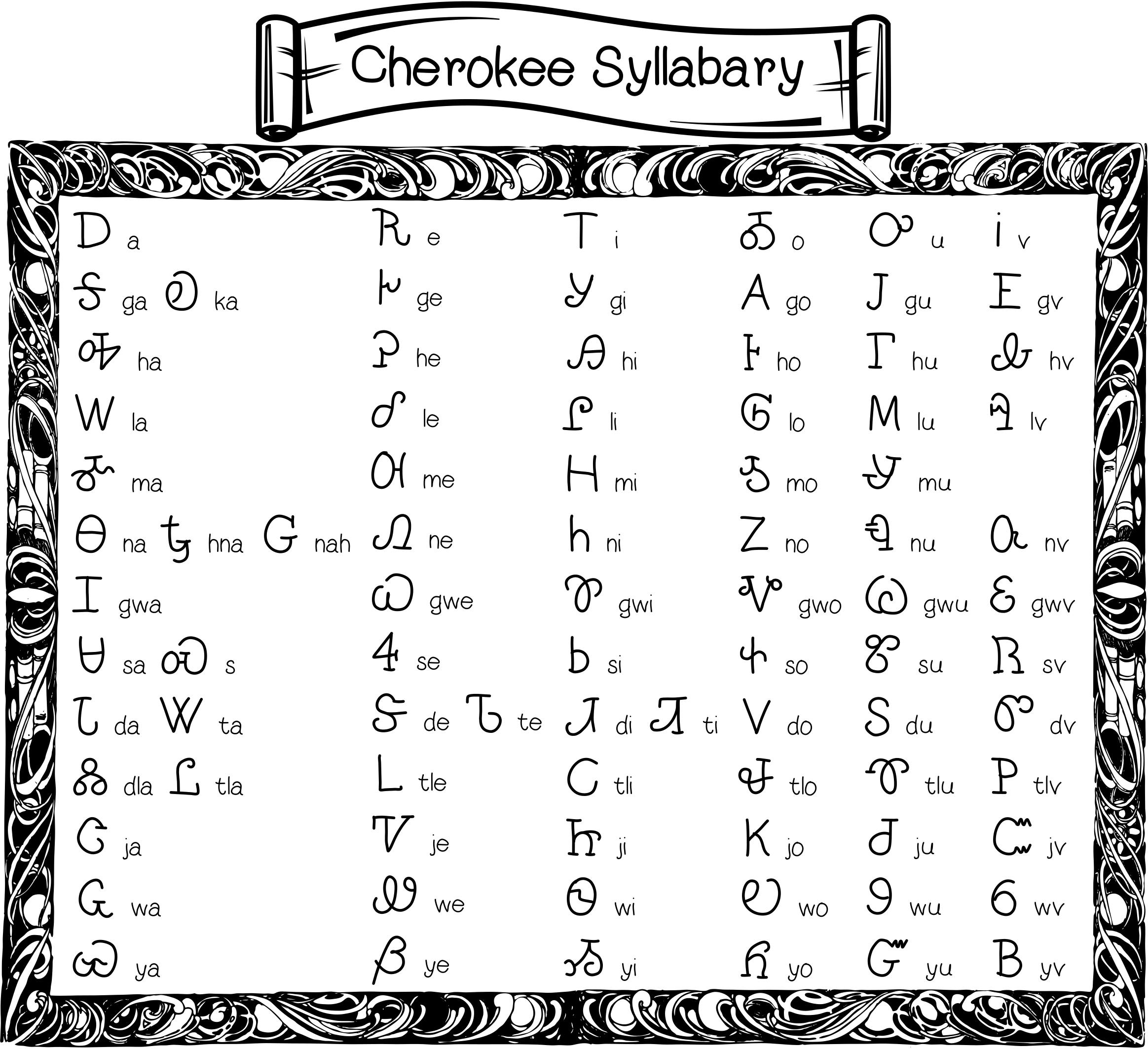

His breakthrough came around 1821. He realized that spoken Cherokee, like many languages, was composed of recurring sounds – syllables. He began to identify each distinct syllable and assign a unique symbol to it. This was his stroke of genius. He recognized that while Cherokee had thousands of words, it had a relatively small number of distinct syllables. The exact number varied slightly over time, but his final system comprised 85 (sometimes cited as 86) characters, each representing a specific syllable, such as "ga," "ho," or "tsu."

To create these symbols, Sequoyah drew inspiration from various sources. Some characters were adapted from English letters he had seen in books or documents, but their phonetic values were entirely different from their English counterparts. For instance, the character that resembles "D" in English actually represents "a," and the one resembling "W" stands for "la." Other characters were entirely his own invention, abstract shapes designed to be distinct and easily recognizable.

The Miracle of Literacy

The true test of his system came with his own family. Sequoyah first taught his young daughter, Ayoka, to read and write the syllabary. Skeptical neighbors witnessed Ayoka and Sequoyah exchanging written messages, a feat that seemed almost magical. To prove its efficacy to the tribal council, Sequoyah proposed a public demonstration. Members of the council would speak words to Ayoka, who would write them down, then Sequoyah would read them back. The process was repeated with other Cherokees. The speed and accuracy with which they communicated using the syllabary utterly astonished the onlookers.

The adoption of the syllabary was nothing short of miraculous. Within a few months, thousands of Cherokees had learned to read and write. Within a decade, it is estimated that literacy rates among the Cherokee Nation surpassed those of their white American neighbors. This rapid spread was due to the inherent simplicity and phonetic efficiency of the syllabary. Unlike alphabetic systems that require learners to master individual letters and then combine them into words, the syllabary allowed individuals to directly connect symbols to the familiar sounds of their spoken language. A person could become functionally literate in Cherokee within days or weeks.

As Sequoyah himself is famously quoted as saying: "I taught myself to read and write. I hope that the Cherokee people will use this as a tool for their future." And they did.

A Nation’s Voice: The Golden Age of Cherokee Literacy

The impact of the syllabary on Cherokee society was immediate and profound, ushering in a "Golden Age" of literacy and self-governance.

In 1828, just seven years after Sequoyah finalized his system, the Cherokee Nation launched the Cherokee Phoenix (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩ ᏧᎴᎯᏌᏅᎯ, Tsalagi Tsulehisanvhi), the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States. Printed in both English and Cherokee (using the syllabary), the Phoenix became a vital tool for communication, disseminating news, laws, and religious texts throughout the nation. Its editor, Elias Boudinot, a prominent Cherokee leader who had been educated in mission schools, eloquently used the paper to articulate the Cherokee Nation’s sovereignty and advocate for its rights against the encroaching tide of white expansion.

The syllabary also played a crucial role in the development of the Cherokee Nation’s written laws and constitution. In 1827, the Cherokee Nation adopted a republican-style constitution, modelled in part on the U.S. Constitution, which was printed in both English and the syllabary. This document formalized their government, complete with legislative, executive, and judicial branches, further asserting their status as a sovereign nation.

Beyond official documents, the syllabary fueled a vibrant culture of personal communication. Cherokees wrote letters to loved ones, kept journals, and recorded their histories and traditions. It became a unifying force, strengthening national identity at a time when external pressures threatened to tear it apart. Missionaries, who had initially struggled to teach English literacy, quickly embraced the syllabary, translating the Bible and other religious texts into Cherokee, further cementing its widespread use.

Enduring Through Adversity: The Trail of Tears

The zenith of Cherokee literacy coincided tragically with one of the darkest chapters in American history: the forced removal of the Cherokee and other Southeastern Indigenous nations from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This brutal ethnic cleansing, known as the Trail of Tears (1838-1839), saw thousands die from disease, starvation, and exposure during the arduous journey.

Yet, even amidst this profound suffering, the syllabary proved to be an unexpected source of strength and resilience. Cherokees wrote letters to each other from the internment camps and along the trail, sharing news, offering comfort, and maintaining connections that transcended the physical hardships. These letters, some of which survive today, bear poignant witness to the enduring power of written language in the face of dehumanization. The ability to read and write in their own language was a testament to their unbroken spirit and cultural continuity.

Modern Echoes and Lingering Challenges

After the removal, the Cherokee Nation re-established itself in Oklahoma, and the syllabary continued to thrive for many decades. Schools taught it, newspapers continued to print, and official documents were still produced in Cherokee. However, as the 20th century progressed, the devastating impact of federal assimilation policies, particularly forced attendance at English-only boarding schools, led to a precipitous decline in the number of fluent Cherokee speakers and, consequently, syllabary users. Generations were punished for speaking their native tongue, leading to a break in linguistic transmission.

Today, the Cherokee language is critically endangered. While there are estimated to be over 400,000 enrolled members of the Cherokee Nation, the number of fluent, first-language speakers has dwindled to only a few thousand, predominantly elders. This decline poses a severe threat to the syllabary’s continued use, as a writing system needs a living language to support it.

However, there is a powerful and growing movement to revitalize the language and, by extension, the syllabary. The Cherokee Nation and other Cherokee communities are investing heavily in language immersion programs, where children learn Cherokee from fluent speakers in a full-immersion environment. The syllabary is taught alongside spoken Cherokee, ensuring that future generations can both speak and read their ancestral language.

Technology has also played a crucial role. The syllabary has been digitized, allowing for its use on computers, smartphones, and in desktop publishing. Unicode support means that the syllabary can be used in emails, social media, and on websites, connecting speakers globally and making the language more accessible to learners. Apps and online resources are helping a new generation engage with this unique script.

The Enduring Legacy

The Cherokee Syllabary remains a monumental achievement, a symbol of Indigenous intellectual prowess and resilience. It is a powerful reminder that literacy is not merely a tool for communication, but a fundamental building block of self-determination, cultural preservation, and national identity.

Sequoyah, the unassuming man who spent years perfecting his system, left behind a legacy that transcends his own time. His syllabary not only enabled a nation to speak to itself in writing but also stands as a beacon for Indigenous peoples worldwide, demonstrating the profound capacity for innovation and self-empowerment that lies within every culture. In a world where language loss continues at an alarming rate, the story of the Cherokee Syllabary offers not just a historical account, but a compelling narrative of hope, resilience, and the enduring power of a people determined to write their own future.