The Earth We Share: Unpacking the Concept of Collective Land Ownership

Land. It is the very foundation of human existence, providing sustenance, shelter, and identity. For much of modern history, our understanding of land ownership has been dominated by two paradigms: private property, where an individual or entity holds exclusive rights, and state ownership, where the government controls vast tracts. Yet, beneath these familiar structures lies a profound, enduring, and increasingly relevant third way: collective land ownership.

Far from being a relic of the past, collective land ownership represents a diverse spectrum of arrangements where land is held, managed, and utilized by a group of people in common. It challenges the atomizing tendencies of private ownership and the often-impersonal nature of state control, offering a vision of shared responsibility and communal benefit. As global challenges like climate change, inequality, and food insecurity intensify, understanding this concept becomes not just an academic exercise but a critical exploration of sustainable and equitable futures.

Defining the Commons: Beyond Individual Titles

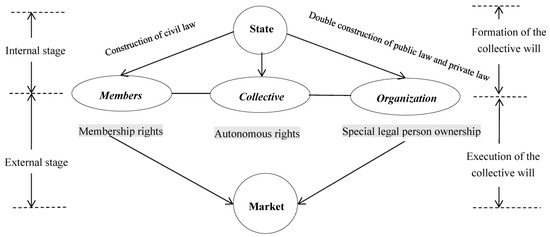

At its core, collective land ownership implies that rights and responsibilities over land are vested not in an individual, but in a defined community or group. This doesn’t necessarily mean an absence of individual use rights, but rather that the ultimate decision-making authority, the long-term stewardship, and often the benefits derived from the land are shared.

"It’s about access, not just ownership," explains Dr. Anya Sharma, a land tenure expert at the University of Cambridge. "In many collective systems, individuals have usufruct rights – the right to use and benefit from the land – but they cannot alienate it, sell it off, or exploit it in ways that harm the collective. This fundamental distinction fosters a long-term perspective that private ownership often lacks."

Unlike state ownership, which is typically top-down and bureaucratic, collective ownership is inherently decentralized and community-driven. Decisions are often made through consensus, traditional governance structures, or democratic processes within the group. The land is seen not merely as a commodity to be bought and sold, but as a shared heritage, a resource to be managed for current and future generations.

A Tapestry of Histories: From Ancient Roots to Modern Forms

The history of collective land ownership is as old as human civilization itself. For millennia, indigenous communities across every continent organized their societies around communal land tenure. From the vast ancestral domains of Aboriginal Australians to the intricate village commons of pre-colonial Africa and Asia, land was rarely seen as something to be privately owned. It was part of the common wealth, a gift from ancestors or deities, managed through intricate customary laws and spiritual connections.

The advent of colonialism, particularly from European powers, dramatically disrupted these systems. European legal frameworks, deeply rooted in Roman law and the concept of individual private property, were forcibly imposed. Vast territories were declared terra nullius (nobody’s land), ignoring existing collective rights, and then parceled out to settlers, corporations, or the colonial state. This historical injustice continues to fuel land conflicts and marginalization in many parts of the world today.

However, collective land ownership did not vanish. It persisted, often underground, and in many places, it has seen a resurgence and formal recognition in the post-colonial era.

Today, collective land ownership manifests in myriad forms:

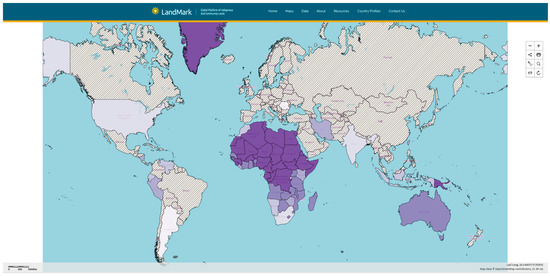

- Customary and Indigenous Lands: Predominant in Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of Asia, and Latin America, these systems are governed by traditional laws and customs. Examples include the Maasai communal grazing lands in Kenya and Tanzania, or the ancestral territories of indigenous groups in the Amazon basin. Rights are often based on lineage, membership in a clan, or residence.

- Ejidos (Mexico): A direct legacy of the Mexican Revolution, ejidos are communal landholdings granted by the state to groups of peasants. While individual members have cultivation rights, the land itself cannot be privately bought or sold. This model sought to redistribute land and empower rural communities.

- Community Land Trusts (CLTs): A modern innovation, particularly in North America and Europe, CLTs separate the ownership of land from the buildings on it. The trust, a non-profit organization governed by community members, owns the land permanently, leasing it to individuals or families for housing or other uses. This keeps land affordable and prevents speculation, often addressing issues of gentrification. Burlington, Vermont, boasts one of the oldest and most successful CLTs in the United States.

- Agricultural Cooperatives and Communes: Groups of farmers pooling resources to manage land collectively, sharing profits and responsibilities. While some may operate on privately owned land, others hold the land collectively, common in parts of Europe and Asia.

- Forest and Fishery Commons: Specific resources like forests or fishing grounds managed collectively by local communities, often under traditional or modern co-management agreements with the state. This is crucial for sustainable resource use.

The Case For: Benefits and Advantages

Proponents argue that collective land ownership offers compelling advantages over purely private or state-centric models:

- Equity and Access: By preventing land from being concentrated in the hands of a few, collective systems promote more equitable access to vital resources. This can significantly reduce poverty and landlessness, particularly in rural areas. "When land is held in common, it ensures that everyone in the community has a stake, fostering a sense of shared prosperity rather than cut-throat competition," notes a report by the International Land Coalition.

- Environmental Stewardship and Sustainability: Communities with a collective stake in their land often have a deeper, long-term incentive to manage it sustainably. Indigenous communities, in particular, are recognized for their profound ecological knowledge and practices that have preserved biodiversity and natural resources for centuries. The Amazon rainforest, for instance, shows significantly lower deforestation rates in indigenous territories where land rights are recognized.

- Cultural Preservation: For indigenous and traditional communities, land is inextricably linked to identity, spirituality, and cultural practices. Collective ownership protects sacred sites, traditional knowledge, and ways of life that would be eroded by fragmentation and commodification.

- Social Cohesion and Resilience: Shared ownership fosters a strong sense of community, mutual support, and collective decision-making. In times of crisis – be it economic downturns or natural disasters – these communities often demonstrate greater resilience due to their interdependent nature.

- Food Security: Collective farming initiatives can enhance local food production, ensuring that communities have direct access to nutritious food and reducing reliance on volatile external markets.

- Protection Against Land Grabs: A recognized collective title can provide a powerful legal shield against large-scale land acquisitions by corporations or governments, safeguarding community livelihoods and resources.

Navigating the Challenges: Complexities and Vulnerabilities

Despite its many advantages, collective land ownership is not without its intricate challenges:

- Governance Complexities: Managing common resources requires robust, transparent, and inclusive governance structures. Disputes over resource allocation, membership rights, and leadership can arise, requiring effective conflict resolution mechanisms. As one elder from a Kenyan pastoralist community lamented, "The old ways of solving disputes are sometimes challenged by new pressures, and our youth are drawn to individual wealth."

- Internal Conflicts: As communities evolve, internal tensions can emerge between different factions, generations, or those with varying economic aspirations. Balancing individual initiative with collective good is a constant negotiation.

- External Pressures and Legal Recognition: Many collective land tenure systems lack formal legal recognition within national frameworks, leaving them vulnerable to encroachment, illegal logging, mining, or large-scale agricultural projects. Even where recognized, the process can be slow and expensive. A 2018 report by the Rights and Resources Initiative found that only 10% of the world’s indigenous and community lands are legally recognized as owned by them.

- Financing and Investment: Attracting external investment for development projects can be difficult when land is not held individually or cannot be used as collateral. This often leads to underdevelopment or the temptation to privatize land to access finance.

- Market Forces and Commodification: The allure of individual wealth and the pressures of market economies can erode communal values, leading to internal desires to privatize or sell off collectively held assets.

The Future of Shared Earth: A Global Imperative

In an era defined by climate crisis, surging inequality, and rapid urbanization, the concept of collective land ownership is gaining renewed attention. From urban farming initiatives to large-scale indigenous land claims, communities worldwide are looking to shared tenure models as a pathway to greater justice and sustainability.

Policy makers and international development organizations are increasingly recognizing the vital role of securing collective land rights for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those related to poverty eradication, food security, gender equality, and climate action. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN emphasizes that "recognizing and securing collective tenure rights is essential for improving livelihoods, ensuring food security, and protecting the environment."

The future likely lies in hybrid models – innovative combinations of collective and individual rights that adapt to contemporary needs while preserving core communal values. This requires robust legal frameworks that protect collective rights, provide avenues for democratic governance, and offer support for sustainable economic activities within collective lands.

Collective land ownership is more than just a legal arrangement; it is a philosophy that re-centers human relationships with the earth and with each other. It reminds us that some things are too precious to be exclusively owned, too vital to be left to the whims of the market, and too fundamental not to be shared. As we confront the profound challenges of the 21st century, revisiting and championing the concept of shared earth might just be our most promising path forward.