Unveiling the Voices: A Journey Through Native American Written Language

The narrative of Native American cultures often conjures images of vibrant oral traditions, intricate storytelling, and profound respect for spoken word. Yet, to assume a complete absence of written language before European contact, or to overlook the ingenious systems developed thereafter, is to miss a crucial, dynamic chapter in human communication. The history of Native American written language is not a monolithic tale, but a rich tapestry woven from ancient visual codes, adaptive innovations, and a relentless drive for self-expression and cultural preservation. It’s a story of resilience, intellect, and the enduring power of the written word to transcend time and adversity.

For centuries, a pervasive misconception held that Native American societies lacked "true" writing systems, defined narrowly by alphabetic or phonetic scripts. This overlooks the sophisticated, albeit non-alphabetic, methods of information storage and transmission that predated European arrival. These systems, while not designed to capture every sound of spoken language, served vital functions for record-keeping, historical narrative, spiritual practice, and inter-tribal communication.

The Ancient Canvases: Pictographs, Petroglyphs, and Beyond

Long before paper and ink, Native Americans inscribed their stories, warnings, and spiritual beliefs onto the very landscape. Pictographs (painted images) and petroglyphs (carved or etched images) adorn rock faces across the continent, from the desert Southwest to the Pacific Northwest. These ancient "rock art" sites, often found in sacred places, served as visual repositories of tribal history, ceremonial instructions, astronomical observations, and hunting records.

Consider Newspaper Rock in Utah, a massive sandstone slab covered with thousands of petroglyphs created over 2,000 years by various Ancestral Puebloan, Fremont, and Ute peoples. While not a phonetic script, the sheer volume and variety of its symbols—human figures, animal tracks, spirals, and abstract designs—clearly indicate a communicative purpose, acting as a historical ledger or a bulletin board for passing groups. Each symbol carried meaning, understood by those within the cultural context, much like a modern logo or icon.

Beyond static rock art, other dynamic systems facilitated complex communication. Wampum belts, crafted from polished shell beads by Northeastern Woodlands tribes like the Iroquois and Algonquian nations, were far more than decorative adornments. Their intricate patterns and colors served as mnemonic devices, historical documents, and diplomatic instruments. Each belt represented a treaty, a significant event, or an agreement, with the specific arrangement of beads encoding the details. When treaties were recited, the wampum belt was "read" aloud, prompting the speaker to recall the exact terms and historical context. As historian Tehanetorens (Ray Fadden) of the Mohawk Nation explained, "Every wampum string and belt has a meaning. The designs and patterns are not just decoration. They were created to record important events and agreements." These were not phonetic scripts, but they were undeniably records, legally binding and historically potent.

Similarly, the Winter Counts of the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota nations were calendrical histories, often painted on buffalo hides. Each year was represented by a unique image or symbol depicting the most significant event of that year. From these visual summaries, tribal historians could recount the full oral history of their people, year by year, sometimes stretching back centuries. For example, a drawing of a smallpox-ridden figure might represent the year of a devastating epidemic, triggering the full narrative of that period. These systems demonstrate an advanced understanding of chronological record-keeping and a sophisticated way to transmit complex information across generations.

The European Imprint and the Spark of Innovation

The arrival of Europeans brought with it a different paradigm of written language: alphabetic scripts based on phonetic principles. For many Native communities, this was initially a tool of the colonizers—missionaries sought to translate the Bible, and government officials aimed to codify laws and treaties. Early attempts to write Native languages often involved adapting the English or Latin alphabet, frequently leading to phonetic inconsistencies and misrepresentations of sounds not present in European languages.

However, this exposure also ignited a spark of indigenous innovation. Native individuals, observing the power and utility of written communication, began to devise their own systems, often uniquely suited to the specific sounds and structures of their languages. This era saw the emergence of truly revolutionary writing systems that would profoundly impact Native American literacy and sovereignty.

Sequoyah’s Genius: The Cherokee Syllabary

The most celebrated and impactful example of indigenous written language development is undoubtedly the Cherokee Syllabary, invented by Sequoyah (also known as George Gist or Guest) in the early 19th century. A Cherokee silversmith who spoke no English, Sequoyah recognized the immense power of written communication after observing the "talking leaves" (books and letters) of European Americans. He understood that literacy could empower his people, protect their culture, and enable them to negotiate on equal terms with the encroaching United States.

For over a decade, Sequoyah tirelessly worked to create a writing system for the Cherokee language. Initially, he attempted a logographic system (one symbol per word), but soon realized the immense number of symbols required would make it impractical. His stroke of genius was to devise a syllabary—a system where each symbol represents a syllable (a consonant-vowel combination), rather than a single letter or a whole word.

Completed around 1821, the Cherokee Syllabary consists of 85 (originally 86) characters. Remarkably, Sequoyah designed these characters from scratch, with no direct influence from English orthography, though some characters coincidentally resemble Latin letters. The syllabary’s brilliance lay in its simplicity and logical structure. With just 85 symbols, a Cherokee speaker could learn to read and write their language with astonishing speed. Within a few years, literacy rates among the Cherokee soared, reportedly exceeding those of their white American neighbors.

The impact was immediate and profound. The Cherokee Nation rapidly adopted the syllabary for government records, laws, and educational materials. In 1828, they launched the Cherokee Phoenix (ᏣᎳᎩ ᏧᎴᎯᏌᏅᎯ), the first newspaper published by Native Americans in the United States, printed in both Cherokee and English. This newspaper became a vital tool for disseminating information, asserting Cherokee sovereignty, and defending their rights against forced removal. The syllabary empowered the Cherokee to articulate their grievances, preserve their traditions, and maintain a unified national identity in the face of immense pressure.

Sequoyah’s invention was not an isolated incident. Inspired by the Cherokee example, other Native American communities and missionaries developed syllabaries or adapted alphabetic scripts for languages like Cree, Ojibwe, and Yup’ik. The Cree Syllabics, developed by missionary James Evans in the 1840s based on principles similar to Sequoyah’s, also achieved widespread adoption and are still used today by Cree and Ojibwe speakers in Canada.

Missionaries, Anthropologists, and the Double-Edged Sword

The story of Native American written language is also intertwined with the efforts of missionaries and later, anthropologists. While their motivations varied—from sincere religious conversion to academic documentation—their work undeniably contributed to the recording and preservation of Native languages, albeit sometimes at a cultural cost.

Early missionaries like John Eliot, in the 17th century, translated the Bible into the Massachusett language, publishing the "Eliot Indian Bible" in 1663. This monumental effort marked the first complete Bible printed in North America and served as a vital record of a language that would otherwise have been largely lost. However, these translations were often part of a broader agenda of assimilation, aiming to replace indigenous spiritual beliefs with Christianity.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as many Native languages faced extinction due to forced assimilation policies and disease, anthropologists like Franz Boas and his students (including Edward Sapir and Alfred Kroeber) undertook extensive efforts to document these languages. They developed phonetic alphabets and orthographies (standardized writing systems) to record oral traditions, vocabularies, and grammatical structures. While their work was crucial for linguistic preservation, it also raised ethical questions about cultural appropriation and the power dynamics inherent in documenting another culture’s intellectual property. The act of "fixing" an oral language into a written form, even with the best intentions, could sometimes alter its fluidity and living nature.

The Era of Loss and the Dawn of Revitalization

The 20th century brought unprecedented challenges to Native American languages, including their written forms. The devastating impact of federal boarding schools, which brutally suppressed indigenous languages and cultural practices, led to a rapid decline in fluency across generations. Children were punished for speaking their native tongues, effectively severing the transmission of linguistic knowledge and cultural identity. This deliberate policy of cultural genocide severely impacted both oral and written traditions.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a powerful resurgence of language revitalization efforts. Tribal communities, scholars, and activists are working tirelessly to reverse the tide of language loss, recognizing that language is intrinsically linked to identity, worldview, and sovereignty. This includes renewed interest in, and creation of, written forms for their languages.

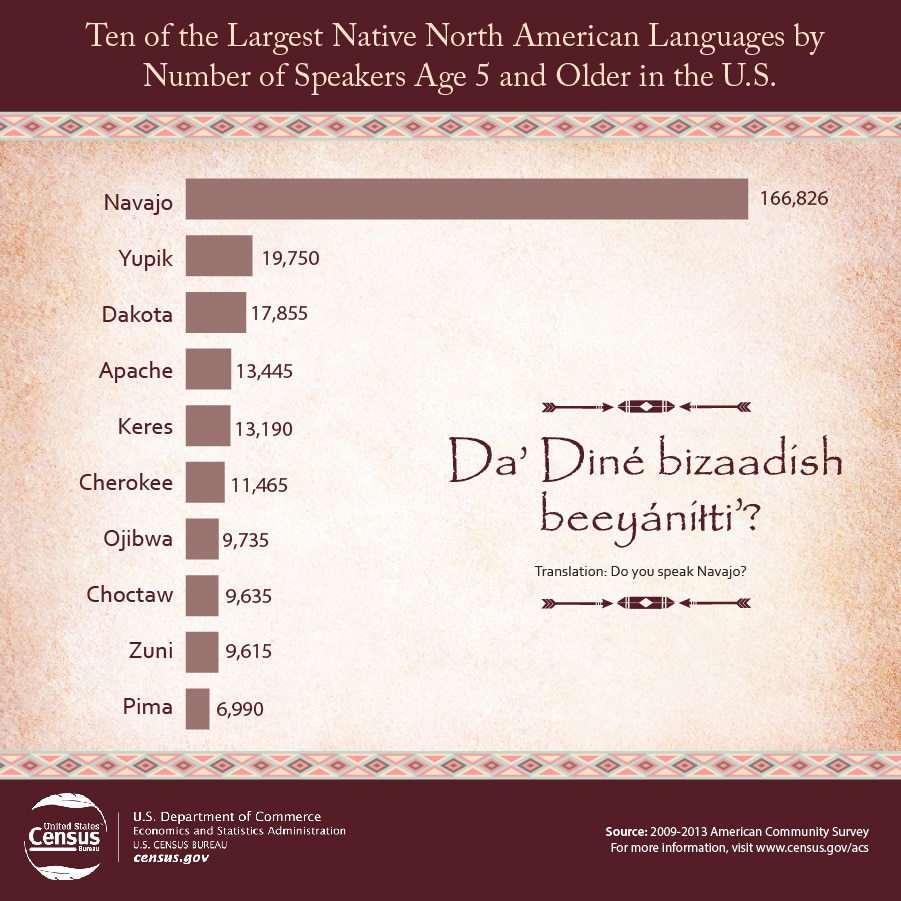

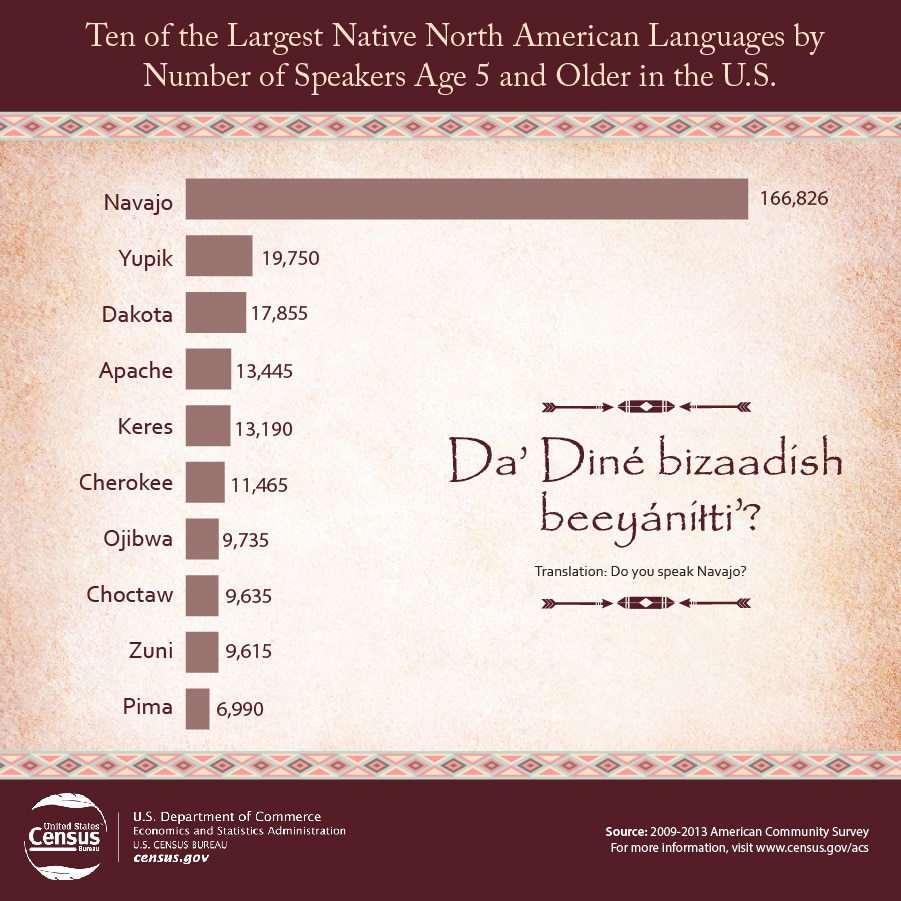

Today, language immersion schools, tribal colleges, and community programs are teaching younger generations their ancestral languages, often utilizing both historical and newly developed orthographies. Digital tools, online dictionaries, and language apps are making it easier for learners to access resources. For example, the Diné (Navajo) language, one of the most widely spoken Native languages, has a standardized writing system that is used in schools, literature, and even on road signs in the Navajo Nation.

Many tribes are meticulously studying the work of earlier linguists and their own elders to reconstruct and standardize writing systems that accurately represent the unique sounds and grammar of their languages. This often involves making decisions about which sounds to represent, how to handle dialectal variations, and how to create user-friendly alphabets or syllabaries that can be taught effectively.

Conclusion: A Continuing Narrative

The history of Native American written language is a testament to human ingenuity and the enduring power of communication. From the ancient petroglyphs whispering stories across millennia to the revolutionary syllabaries that empowered nations, and the ongoing revitalization efforts of today, it is a story of adaptation, resilience, and profound cultural richness.

It challenges us to broaden our understanding of what "writing" truly means and to appreciate the diverse ways in which human societies have encoded knowledge and preserved their legacies. The journey of Native American written language is far from over; it is a dynamic, living narrative, continually evolving as communities reclaim their linguistic heritage, ensuring that their voices, in all their written forms, continue to resonate for generations to come. Recognizing and celebrating this history is not just an academic exercise; it is an act of respect for the intellectual heritage and ongoing sovereignty of Native American peoples.