On the Front Lines: How Climate Change Disproportionately Impacts Native American Tribes

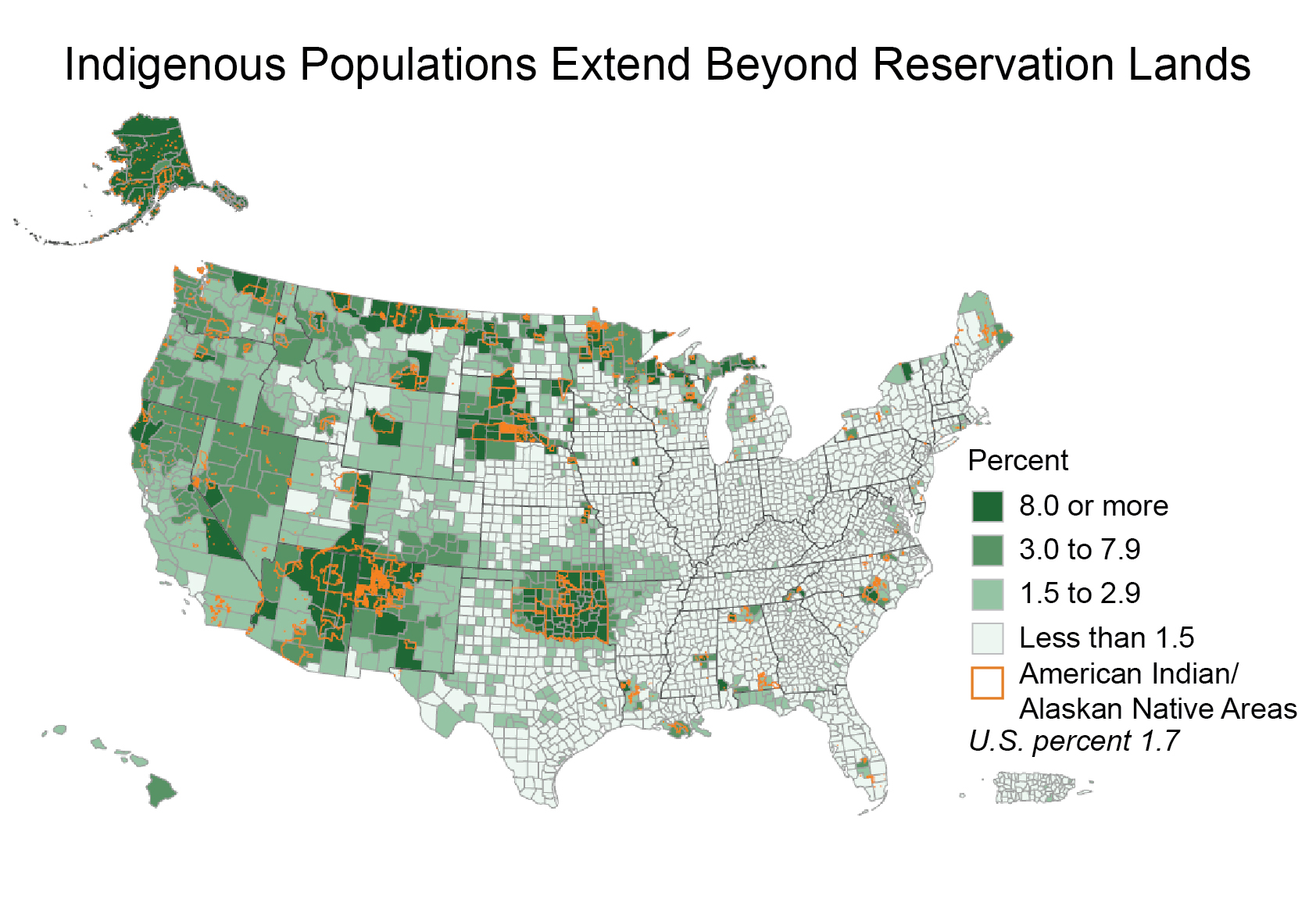

The drums of change beat a different rhythm for Native American tribes across the United States. While the world grapples with the existential threat of climate change, Indigenous communities find themselves on the front lines, facing disproportionate impacts that threaten their very existence, culture, and way of life. For centuries, these tribes have lived in intimate connection with the land, their traditions, languages, and spiritual practices interwoven with the natural world. Now, as temperatures rise, waters recede or surge, and ancient rhythms are disrupted, this profound connection becomes a source of extreme vulnerability.

The disproportionate impact stems from a complex interplay of historical injustices, geographical realities, and deep cultural reliance on natural resources. Decades of forced relocation, land dispossession, and assimilation policies have left many tribes with limited economic resources and often confined to lands most susceptible to environmental shifts. Their traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), honed over millennia, once allowed them to adapt to natural cycles, but the pace and scale of human-induced climate change are unprecedented, pushing their resilience to its limits.

Water Scarcity and Contamination: A Looming Crisis

For many tribes, water is life, sacred, and fundamental to their identity. The escalating climate crisis manifests dramatically in altered water patterns, threatening both access and quality.

In the arid Southwest, the Navajo Nation, the largest tribal nation in the U.S., faces severe and worsening drought conditions. The Colorado River, a lifeline for 40 million people, including 30 Native American tribes, is experiencing its lowest flows in over a century. For the Navajo, Hopi, and other Pueblo tribes, this means parched lands, failing crops, and diminished access to potable water. Many Navajo homes still lack running water, relying on wells that are now drying up or becoming contaminated. "Our elders remember a time when the washes flowed freely, when our crops flourished with rain," says a Navajo elder, her voice heavy with concern. "Now, the land is thirsty, and so are our people. How can we practice our ceremonies, grow our food, without water?" The lack of reliable water sources not only impacts agriculture and daily life but also undermines traditional ceremonies and healing practices intrinsically linked to water.

Conversely, some areas face the threat of increased flooding. The Quinault Indian Nation on Washington’s coast, for instance, has seen its traditional fishing grounds impacted by ocean acidification and rising sea levels, while increased storm surges threaten coastal communities and infrastructure. Contaminated runoff from more intense precipitation events also poses a significant health risk, particularly for communities reliant on subsistence fishing and traditional food gathering.

Threats to Food Security and Traditional Sustenance

The direct link between land and sustenance means climate change directly imperils tribal food security and cultural practices. Traditional foods are not merely calories; they are medicine, ceremony, and identity.

For the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) people of the Great Lakes region, Manoomin (wild rice) is a sacred grain, central to their diet, economy, and spiritual well-being. Climate change threatens Manoomin through erratic precipitation patterns – too much rain can wash away young plants, while drought can prevent growth. Rising water temperatures also make lakes less hospitable for the rice. "Our wild rice is our history, our language, our future," explains an Ojibwe community leader. "If the rice disappears, a part of us disappears." Efforts are underway to protect and restore wild rice beds, but the scale of the climate threat is immense.

Similarly, Pacific Northwest tribes, such as the Nez Perce, Yurok, and Lummi, are witnessing the devastating decline of salmon populations. Warmer river temperatures stress the fish, making them more susceptible to disease, while altered stream flows disrupt spawning cycles. Ocean acidification also impacts the marine food web that salmon depend on. For these tribes, salmon are a cornerstone of their cultural and spiritual identity, their economy, and their diet. The annual salmon run is a time of ceremony and celebration; its decline represents not just a food shortage but a profound cultural loss.

In the Great Plains, tribes historically reliant on the buffalo face challenges from habitat degradation due to drought and shifting ecosystems, impacting conservation efforts crucial for the species’ recovery.

Cultural Erosion and Health Impacts

The impact of climate change extends beyond the physical environment, deeply affecting the cultural fabric and mental health of Indigenous communities. Sacred sites, many of which are tied to specific geological features or seasonal events, are being threatened by erosion, sea-level rise, or extreme weather. Ancient burial grounds and historical artifacts are at risk.

The mental and emotional toll is immense. The grief associated with watching ancestral lands change beyond recognition, the loss of traditional foods, and the uncertainty of future generations’ ability to practice their culture creates widespread distress, often referred to as "eco-grief" or "solastalgia." Rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health challenges can rise in communities experiencing such profound ecological and cultural disruption.

Furthermore, health impacts are direct and varied. Increased heat waves disproportionately affect elders and those with pre-existing conditions. Changes in vector-borne diseases (like Lyme disease from ticks or West Nile virus from mosquitoes) are also a growing concern as their ranges expand with warmer temperatures. Food insecurity can lead to nutritional deficiencies and related health issues.

Forced Migration: A New Chapter of Displacement

For some Native American communities, climate change is forcing a new, painful chapter of displacement. Alaska Native villages, particularly those on the coast or in the permafrost regions, are among the most vulnerable communities in the world. Rising sea levels, eroding coastlines, and melting permafrost are making their homes uninhabitable.

The Yup’ik village of Newtok, Alaska, has been a stark example. Built on permafrost that is rapidly thawing, and battered by increased storm surges, the village has been slowly sinking and eroding. Its residents have embarked on a decades-long, arduous, and underfunded effort to relocate to higher, more stable ground at Mertarvik. This is not a simple move; it’s a monumental undertaking that requires rebuilding an entire community, maintaining cultural cohesion, and securing vast financial resources. The experience of Newtok is a harbinger for dozens of other Alaskan villages facing similar fates, like Shishmaref, whose island home is shrinking year by year. These are not merely environmental refugees; they are climate refugees, forced to abandon ancestral lands that hold their history, their identity, and their future.

Resilience, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and Self-Determination

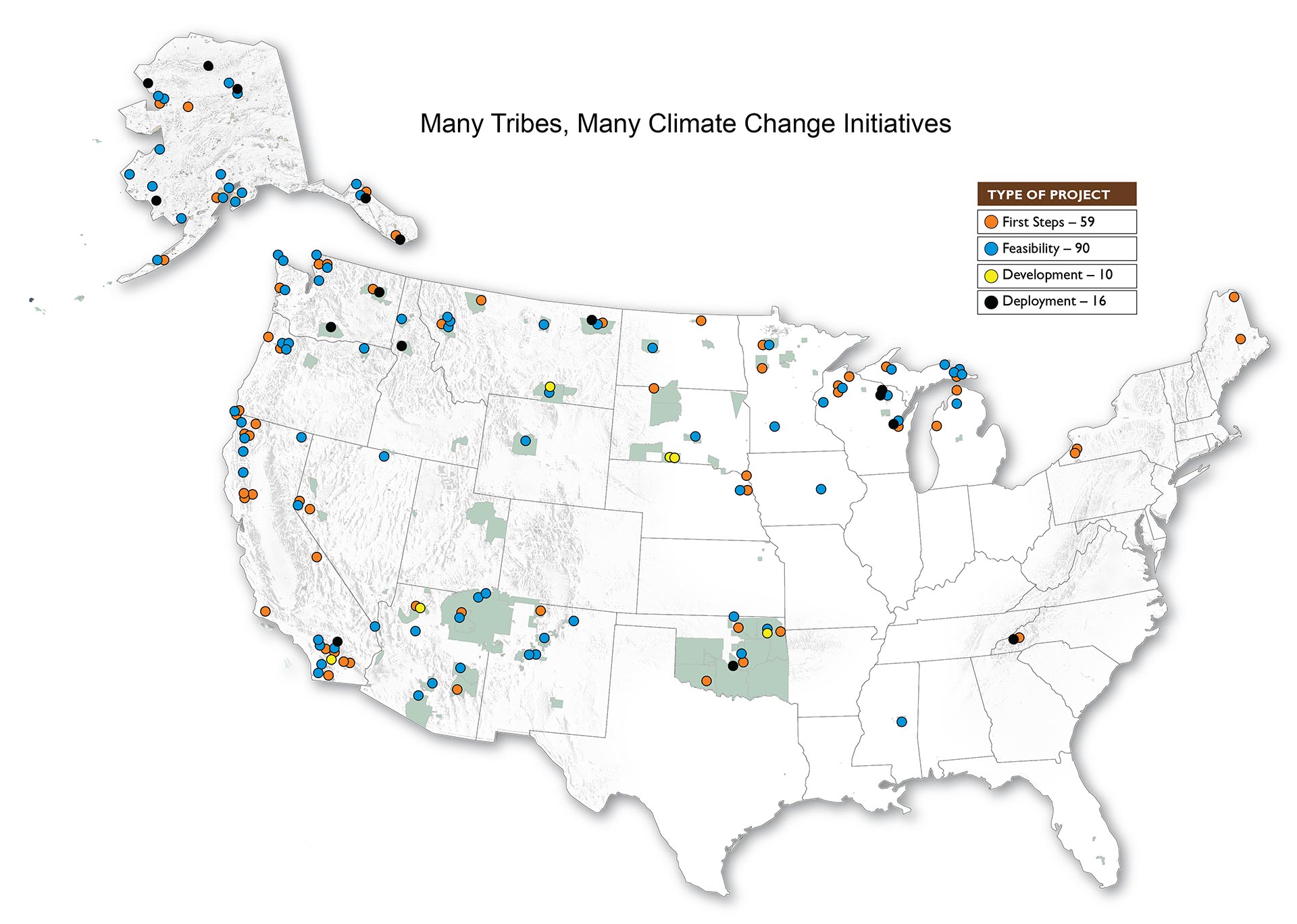

Despite the overwhelming challenges, Native American tribes are not passive victims. They are leading efforts in adaptation, mitigation, and advocacy, drawing upon their profound Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and asserting their inherent sovereignty.

TEK, often passed down through generations of oral histories and practices, encompasses deep understanding of local ecosystems, weather patterns, plant and animal behaviors, and sustainable resource management. It offers invaluable insights for climate adaptation. For example, some tribes are using traditional fire management techniques to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires, while others are reintroducing native plant species better suited to changing conditions. The Menominee Nation in Wisconsin, renowned for its sustainable forestry practices, exemplifies how TEK combined with modern science can create resilient ecosystems.

Tribes are also asserting their self-determination and sovereignty to drive their own climate solutions. They are forming inter-tribal coalitions, advocating for policy changes at the federal level, and securing funding for adaptation projects. They demand a seat at the table in climate negotiations, arguing that their unique perspectives and experiences are crucial for effective global solutions. Many are developing their own climate action plans, often incorporating spiritual and cultural values alongside scientific data.

However, these efforts are often hampered by chronic underfunding, bureaucratic hurdles, and a lack of recognition from federal and state governments regarding tribal sovereignty. The resources needed to relocate entire villages, restore damaged ecosystems, or build resilient infrastructure are immense, far exceeding what is currently available.

A Shared Future

The plight of Native American tribes in the face of climate change is a powerful testament to the interconnectedness of humanity and the environment. Their struggles highlight the urgent need for environmental justice, recognizing that those who have contributed least to the crisis often bear its heaviest burdens.

As the world grapples with a warming planet, listening to Indigenous voices and supporting their self-determined solutions is not merely an act of justice; it is an act of collective wisdom. Their thousands of years of stewardship, their profound understanding of ecological balance, and their inherent resilience offer invaluable lessons for all of humanity. The survival of their cultures, languages, and ways of life in the face of climate change is a bellwether for our shared future. Their fight is our fight, and their survival is a measure of our collective commitment to a just and sustainable world.