The Crisis of the Missing and Murdered: Unveiling the MMIW Epidemic Plaguing Indigenous Communities

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

Imagine a world where your sisters, mothers, daughters, and aunties disappear without a trace, or are found murdered, with their cases often dismissed, mishandled, or left unsolved. This is not a dystopian nightmare; it is the grim reality for thousands of Indigenous families across North America, caught in the throes of what is now widely recognized as the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) crisis. Far from an isolated issue, MMIW is a systemic epidemic, deeply rooted in centuries of colonialism, discrimination, and a profound failure of justice systems.

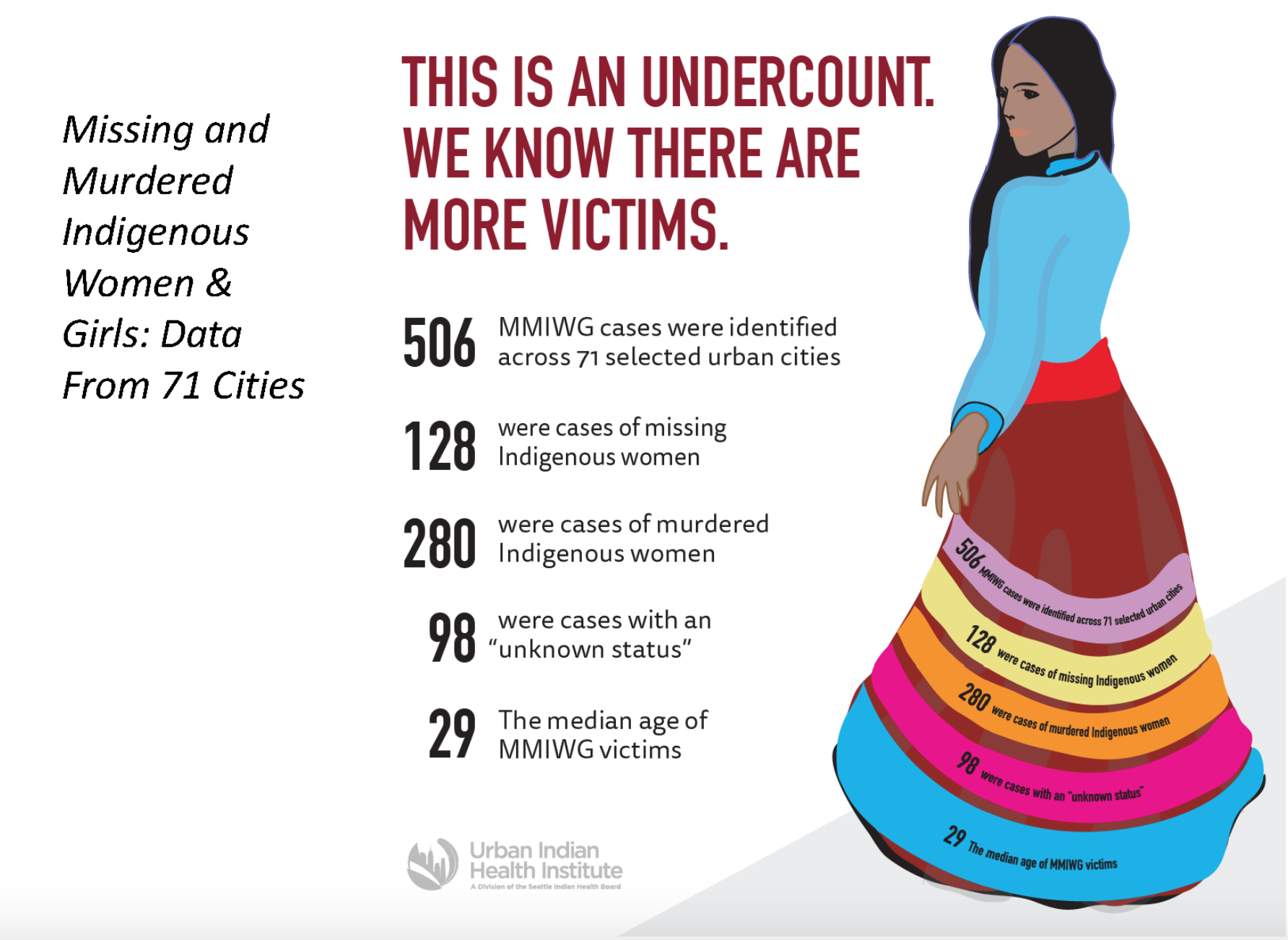

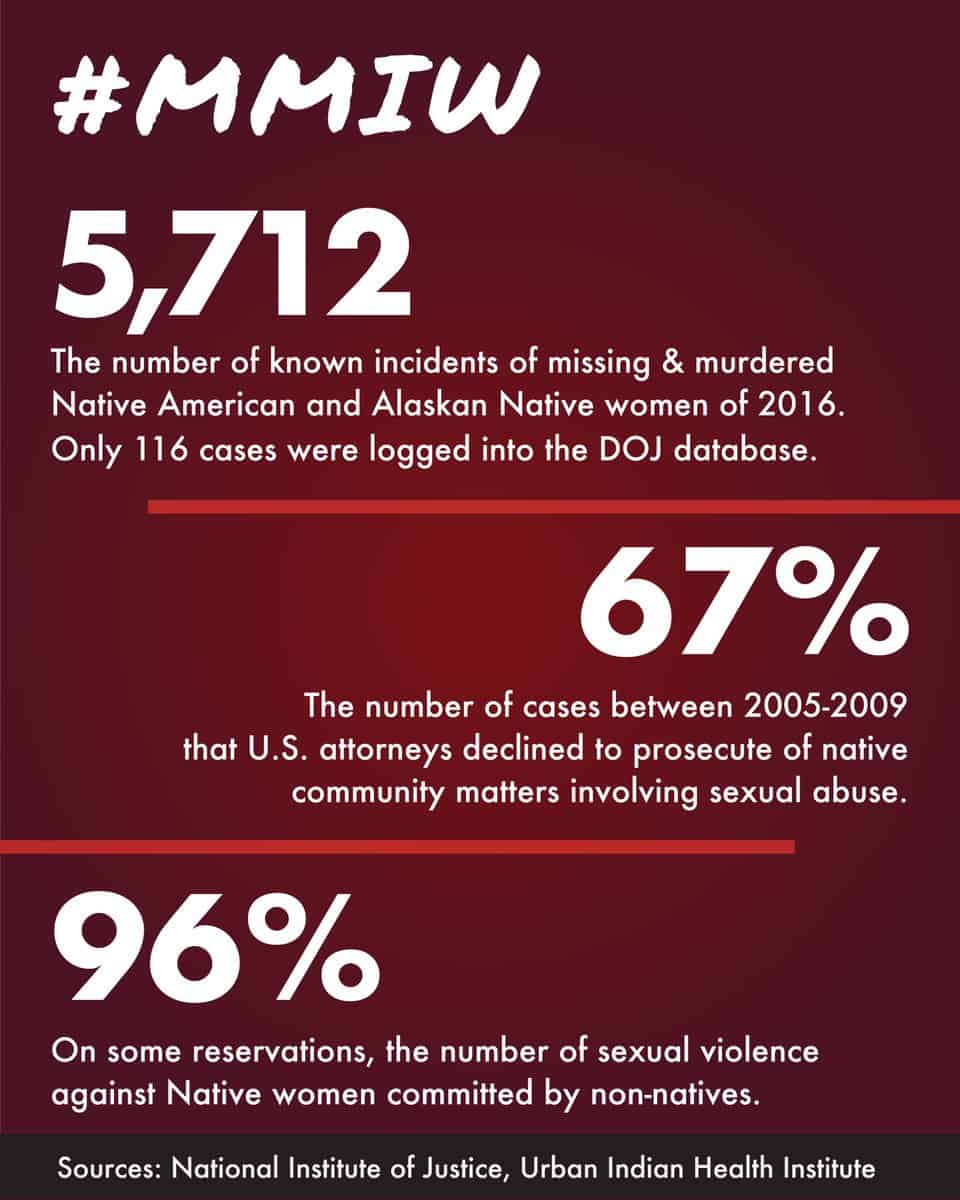

The acronym MMIW, often expanded to MMIWG (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls) or MMIWGT2S+ (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Two-Spirit, and Plus people), represents a harrowing surge of violence disproportionately affecting Indigenous populations. While precise, comprehensive data remains tragically elusive due to historic underreporting and misclassification, the statistics that do exist paint a chilling picture. A 2016 study by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) found that more than four out of five Indigenous women (84.3%) have experienced violence in their lifetime, with over half (56.1%) having experienced sexual violence. For many, this violence escalates to abduction and murder at rates significantly higher than for any other demographic group.

"This isn’t just a crisis; it’s an ongoing genocide," states a leading Indigenous advocate, reflecting the widespread sentiment within affected communities. "Our women are sacred, they are our life-givers, our knowledge keepers. When they go missing, or are taken from us, it’s not just a loss for the family, but for the entire nation."

The Scope of the Unseen Epidemic

The true scope of the MMIW crisis is difficult to quantify, largely due to systemic failures in data collection. Many cases go unreported, or are misclassified by law enforcement, often due to jurisdictional complexities, racial bias, or a lack of understanding of Indigenous communities.

For instance, the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) reported in 2018 that while there were 5,712 cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls in 2016, only 116 of these cases were logged in the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database. This staggering disparity highlights a fundamental issue: a vast number of cases are simply not acknowledged by the very systems meant to protect and serve.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that homicide is the third leading cause of death among Indigenous women aged 10-24. In some areas, the murder rate for Indigenous women is ten times the national average. These aren’t just numbers; they represent countless lives cut short, families shattered, and communities scarred by an enduring trauma.

Roots in History: Colonialism and Systemic Disregard

To understand the MMIW crisis, one must delve into its historical roots. Centuries of colonialism have systematically eroded Indigenous sovereignty, culture, and social structures. The forced removal from ancestral lands, the genocidal policies of residential and boarding schools designed to "kill the Indian in the child," and the imposition of foreign governance have created a legacy of intergenerational trauma, poverty, and social disarray.

"Our communities have been under attack for generations," explains an elder from a Plains tribe. "The violence against our women today is a direct consequence of the violence against our lands, our languages, our spiritual practices. When you strip a people of their identity and their protectors, you leave them vulnerable."

This historical context is crucial. It explains why Indigenous women, often facing a nexus of racism, sexism, and poverty, are particularly susceptible to violence. Their vulnerability is exacerbated by the breakdown of traditional family structures and the lack of essential services like healthcare, housing, and robust law enforcement in many remote tribal communities.

A Labyrinth of Injustice: The Jurisdictional Maze

One of the most significant barriers to justice for MMIW victims and their families is the complex and often convoluted jurisdictional landscape. In the United States, criminal jurisdiction on tribal lands can be a tangled web involving tribal, state, and federal authorities. Depending on the nature of the crime, the tribal affiliation of the victim and perpetrator, and where the crime occurred, different agencies may have primary jurisdiction—or no jurisdiction at all.

For example, if a non-Native person commits a serious crime against an Indigenous person on tribal land, tribal courts often lack the authority to prosecute them, leaving it to federal or state authorities who may be geographically distant, under-resourced, or culturally insensitive. This jurisdictional maze creates gaps that perpetrators exploit, leading to delayed investigations, lost evidence, and ultimately, unsolved cases.

"We report our missing loved ones, and often we’re met with indifference, or told it’s a domestic dispute, or that they probably just ran away," recounts a family member whose sister disappeared years ago. "There’s no sense of urgency, no proper investigation. It’s like our lives don’t matter as much."

Contributing Factors: The Modern Landscape of Risk

Beyond historical trauma and jurisdictional challenges, several contemporary factors contribute to the MMIW crisis:

- Resource Extraction Industries ("Man Camps"): The proliferation of temporary housing sites for predominantly male, non-Indigenous workers in industries like oil, gas, and mining (often referred to as "man camps") near tribal lands has been directly linked to increased rates of sexual assault, human trafficking, and violence against Indigenous women. These transient populations often bring with them increased drug and alcohol use, and a sense of impunity.

- Human Trafficking: Indigenous women and girls are disproportionately targeted by human traffickers, often lured from impoverished communities with false promises of jobs or a better life, only to be forced into sexual exploitation or forced labor.

- Lack of Infrastructure and Resources: Many Indigenous communities, particularly those in remote areas, lack adequate infrastructure, including reliable communication systems, emergency services, and well-funded tribal law enforcement. This isolation makes it easier for crimes to occur unnoticed and harder for victims to seek help.

- Systemic Bias in Media and Law Enforcement: The MMIW crisis also suffers from a severe lack of media attention compared to cases involving non-Indigenous women, perpetuating a cycle of invisibility. Law enforcement agencies have also been criticized for racial profiling, inadequate training on tribal sovereignty, and a general dismissiveness towards cases involving Indigenous victims.

The Human Cost and the Fight for Justice

The MMIW crisis is not just about statistics; it’s about the profound human cost. Each missing or murdered person leaves an aching void in their family and community. The loss of Indigenous women, who often serve as cultural pillars, language keepers, and matriarchs, further erodes the fabric of tribal nations. Families are left in perpetual limbo, enduring years of agonizing uncertainty, unable to grieve properly or find closure.

In response, Indigenous communities and their allies have galvanized into a powerful movement. The #MMIW hashtag and the striking image of red dresses hanging in public spaces (symbolizing the spirits of missing and murdered Indigenous women) have become global symbols of awareness and a call for action. Grassroots organizations, often led by the families of victims, are at the forefront of advocacy, organizing searches, supporting grieving families, and pushing for policy changes.

"We wear red to remember, to honor, and to fight," says a participant at an MMIW rally. "We are not disposable. Our voices will be heard, and we will demand justice for our stolen sisters."

Moving Forward: Legislation, Self-Determination, and Healing

While the scale of the crisis is daunting, there has been some progress in recent years. In the United States, federal legislation like Savanna’s Act (2020) and the Not Invisible Act (2020) aim to improve data collection, coordination between agencies, and establish a commission to combat violent crime against Indigenous people. In Canada, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, released in 2019, detailed the systemic causes of violence and offered 231 Calls for Justice.

However, legislation alone is not enough. True progress requires a multifaceted approach:

- Improved Data Collection: Standardized and comprehensive data collection across all jurisdictional levels is critical to accurately understand the scope of the problem and allocate resources effectively.

- Enhanced Law Enforcement Training: Police officers and legal professionals need culturally competent training to understand the unique challenges and historical context of Indigenous communities.

- Addressing Root Causes: Long-term solutions must tackle the systemic issues of poverty, lack of housing, inadequate healthcare, and historical trauma that contribute to vulnerability.

- Empowering Tribal Sovereignty: Strengthening tribal justice systems and respecting tribal self-determination are crucial. Indigenous-led solutions, rooted in traditional knowledge and community values, are often the most effective.

- Public Awareness and Allyship: Continued public education is vital to dismantle stereotypes and foster empathy and support for Indigenous communities.

The MMIW crisis is a stain on the conscience of nations that claim to uphold justice and human rights. It is a testament to the devastating legacy of colonialism and the enduring struggle for Indigenous sovereignty and safety. The call from Indigenous communities is clear: End the violence, find the missing, seek justice for the murdered, and ensure that no more lives are lost to indifference and systemic neglect. Only then can true healing begin, and the silent epidemic finally be brought to light and to an end.