Echoes of the Shining Mountains: Unraveling the Enduring History of the Ute People

The Ute people, known to themselves as Nuche, or "The People," have for millennia inhabited a vast and rugged landscape spanning what is now Colorado, Utah, and parts of New Mexico and Wyoming. Their history is a profound testament to resilience, adaptation, and an unbreakable bond with the land – a narrative woven through ancient traditions, dramatic transformations, and enduring struggles against overwhelming odds. From their ancestral homelands among the "Shining Mountains" to their contemporary roles as sovereign nations, the story of the Ute is a vital chapter in the broader tapestry of American history, often overlooked but deeply impactful.

The Ancient Roots: Nomads of the High Country

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Ute were master hunter-gatherers, intimately familiar with the rhythms of their environment. Their traditional territory, often referred to as Ute-land, stretched from the Great Salt Lake in the west to the Continental Divide in the east, and from the Wyoming plains south into the desert mesas of New Mexico. They were not a single, monolithic tribe but rather a collection of seven major bands – the Capote, Faraon, Moache, Parianuche, Tabeguache (later Uncompahgre), Timpanogos, and Weeminuche – each with distinct territories but sharing a common language (a Uto-Aztecan dialect), cultural practices, and spiritual beliefs.

Their lives revolved around seasonal movements, following game and harvesting wild plants. Deer, elk, and bison were central to their diet, providing not only sustenance but also hides for clothing and shelter. Pinyon nuts, berries, and roots supplemented their diet. "The mountains were our supermarkets, our churches, our homes," a contemporary Ute elder might explain, encapsulating the deep spiritual and practical connection to their environment. Their knowledge of the land was encyclopedic, allowing them to thrive in diverse ecosystems ranging from alpine forests to arid deserts. Social structures were fluid, based on family groups and band affiliations, with leadership emerging through wisdom, hunting prowess, and spiritual insight.

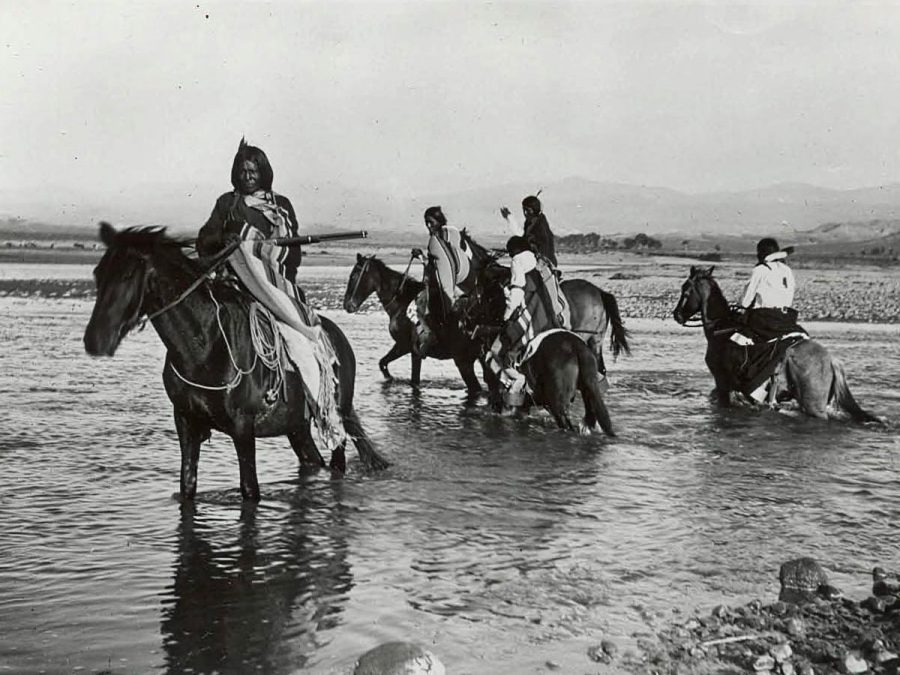

The Horse Revolution and European Encounters

The 17th century brought a seismic shift to Ute life with the introduction of the horse by Spanish colonizers. Acquired through trade or capture, horses rapidly transformed Ute culture. They became more efficient hunters, able to pursue bison on the plains, and their mobility increased dramatically, expanding their hunting ranges and facilitating trade networks. The Ute became formidable horsemen, renowned for their skill and daring. This new power also brought them into more frequent contact, and sometimes conflict, with neighboring tribes like the Navajo, Shoshone, and Comanche, as well as with the Spanish.

Initial interactions with the Spanish were complex. While some Ute bands engaged in trade, exchanging hides and slaves for horses and metal goods, others fiercely resisted Spanish encroachment. The Spanish established missions and settlements in New Mexico, pushing into Ute lands. Disease, a silent but devastating killer, accompanied European contact. Smallpox, measles, and other pathogens, against which Native populations had no immunity, decimated Ute communities, often preceding direct military conflict. This era marked the beginning of a long and tragic pattern: the erosion of Ute populations and territory due to external forces.

The American Onslaught: Treaties, Gold, and Displacement

The 19th century ushered in an even more profound challenge: the westward expansion of the United States. Following the Louisiana Purchase and the Mexican-American War, American settlers, fur trappers, and prospectors poured into Ute territory. The U.S. government, driven by Manifest Destiny and the promise of land and resources, adopted a policy of "Indian Removal" and "Manifest Destiny."

The discovery of gold in Colorado in 1859, specifically the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, triggered an unprecedented influx of miners and settlers onto Ute lands. The Ute, initially viewing these newcomers with cautious curiosity, soon realized the existential threat they posed. Their traditional hunting grounds were disrupted, their sacred sites desecrated, and their very way of life imperiled.

A series of treaties, often negotiated under duress and with little understanding of Ute political structures, marked a systematic divestment of Ute lands:

- Treaty of 1863: The Tabeguache Ute, under immense pressure, ceded significant lands in central Colorado, agreeing to move to a reservation in the San Luis Valley.

- Treaty of 1868 (The Brunot Treaty): This was a pivotal moment. All Ute bands were forced to cede most of their remaining lands in Colorado, confining them to a large reservation in the western part of the state. This treaty, however, still promised them the continued use of vast hunting grounds.

- Treaty of 1873: Driven by renewed gold and silver strikes in the San Juan Mountains, the government coerced the Ute into ceding the mineral-rich San Juan region, further shrinking their reservation. Ouray, a prominent Uncompahgre Ute chief, known for his diplomatic efforts to protect his people, famously stated, "The agreement to which I have assented is the best that could be done under the circumstances." His words highlighted the impossible choices faced by Ute leaders.

These treaties were consistently violated by settlers and the government, who continued to encroach on remaining Ute lands.

The Meeker Massacre and Forced Removal

The breaking point came in 1879 at the White River Agency in northwestern Colorado. Nathan Meeker, the Indian Agent, sought to "civilize" the Ute by forcing them to adopt farming and abandon their traditional ways. He plowed over their horse racing tracks and tried to convert them to Christianity, showing profound disrespect for their culture. Tensions escalated, leading to a desperate appeal from Meeker for military intervention.

On September 29, 1879, Major Thomas Thornburgh’s troops, en route to the agency, were ambushed by Ute warriors, leading to the "Meeker Massacre." Meeker and several of his employees were killed at the agency, and women and children were taken captive. The incident ignited a national outcry, fueling anti-Ute sentiment and providing the justification for their final removal from Colorado.

Despite the fact that only a portion of the Ute population was involved in the conflict, the tragedy served as a convenient pretext for the government to implement its long-desired policy: the complete removal of the Ute people from Colorado. In 1881, the Northern Ute bands (White River and Uncompahgre) were forcibly relocated to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in northeastern Utah, a land vastly different and less hospitable than their ancestral homelands. The Southern Ute and Mountain Ute bands were eventually confined to smaller, separate reservations in southwestern Colorado, a fraction of their original territory.

This forced removal was a traumatic experience, severing the Ute from generations of ancestral lands, sacred sites, and traditional resources. It was a calculated act of cultural destruction, designed to assimilate them into American society.

The Reservation Era and the Fight for Sovereignty

Life on the reservations was harsh. The Ute faced poverty, disease, and a constant assault on their cultural identity through government policies like the Dawes Act (1887), which aimed to break up tribal lands into individual allotments, and the boarding school system. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their language or practice their traditions, in an attempt to "kill the Indian to save the man." Yet, the Ute people persevered. Their language, stories, and ceremonies were kept alive, often in secret, by dedicated elders and families.

The 20th century saw a slow, arduous path toward self-determination. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 provided some relief, allowing tribes to re-establish their governments. However, the mid-century "Termination Era" (1950s-1960s) again threatened tribal sovereignty, seeking to dissolve tribal entities and assimilate Native Americans fully. The Ute, like many tribes, fought vehemently against termination, successfully preserving their federally recognized status.

Today, there are three federally recognized Ute tribes:

- The Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah and Ouray Reservation: Located in Fort Duchesne, Utah, they are the largest of the three tribes in terms of land base.

- The Southern Ute Indian Tribe: Based in Ignacio, Colorado, they are a vibrant and economically successful tribe.

- The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe: With headquarters in Towaoc, Colorado, their reservation also extends into New Mexico and Utah, encompassing the stunning Mesa Verde National Park.

These modern Ute nations have asserted their sovereignty, managing their own affairs, developing their economies, and working tirelessly to preserve and revitalize their culture. They have engaged in significant legal battles, particularly over water rights, a critical resource in the arid West, often winning landmark cases that affirm their inherent rights as original inhabitants.

Economically, many Ute tribes have diversified, investing in energy resources, tourism, and gaming. The Southern Ute Indian Tribe, for example, is one of the wealthiest tribes in the United States, utilizing natural gas and oil revenues to fund tribal services, education, and economic development. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe operates the Ute Mountain Casino Hotel, a significant source of revenue and employment.

Culturally, there is a renewed emphasis on language preservation, traditional ceremonies like the Bear Dance and the Sun Dance, and historical education. Young Ute people are learning their language, participating in traditional arts, and reconnecting with their ancestral heritage, ensuring that the "People of the Shining Mountains" continue to thrive.

An Enduring Legacy

The history of the Ute people is a powerful narrative of survival and resilience against the backdrop of immense historical pressures. From their ancient nomadic existence to their forced displacement and the ongoing struggle for self-determination, the Ute have consistently demonstrated their strength and adaptability. Their story is not just one of loss and injustice, but also of an unwavering spirit, a profound connection to their ancestral lands, and a vibrant future.

As the Ute nations continue to assert their sovereignty and build prosperous communities, their history serves as a poignant reminder of the complex and often painful legacy of westward expansion, but also as an inspiring testament to the enduring power of culture, identity, and the human spirit. The echoes of the Shining Mountains continue to resonate, carrying the voices of "The People" into the future.