Guardians of the Forest: The Enduring Legacy of Northeast Woodlands Tribes

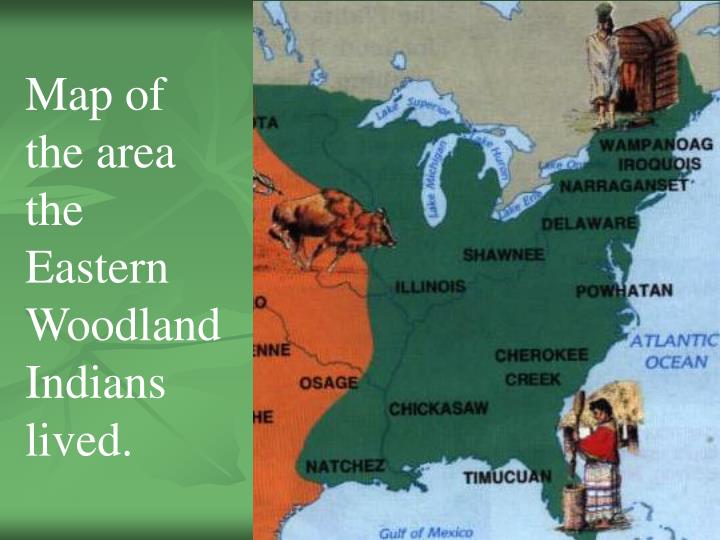

Imagine a landscape shaped by ancient ice, carved into rolling hills, deep valleys, and a vast network of rivers and shimmering lakes, all blanketed by dense, deciduous and coniferous forests. This is the Northeast Woodlands, a region stretching from the Atlantic coast westward to the Great Lakes, and from the St. Lawrence River south to the Ohio River Valley. For millennia before European contact, this vibrant land was home to a rich tapestry of Indigenous nations, each with unique customs, languages, and social structures, yet all intrinsically connected to the rhythms of the forest and its abundant resources.

These were not homogenous peoples, but diverse sovereign nations, primarily categorized into two major linguistic families: the Algonquian and the Iroquoian. Their ingenuity, adaptability, and profound spiritual connection to the land enabled them to thrive in an environment characterized by harsh winters, humid summers, and a bounty of wildlife and plant life. Understanding these tribes means peeling back layers of history, dispelling myths, and recognizing the profound legacy that continues to shape the region today.

The Landscape as a Classroom and Sustainer

The Northeast Woodlands environment dictated much of the Indigenous way of life. The dense forests provided timber for housing, canoes, and tools; game like deer, bear, moose, and countless smaller animals for food and pelts; and an endless variety of nuts, berries, roots, and medicinal plants. The rivers and lakes teemed with fish, and served as vital transportation routes, navigated by expertly crafted birchbark canoes – vessels that symbolized the deep connection between people and their natural surroundings. As the seasons turned, so did the activities: spring brought maple sugaring and planting, summer was for cultivating and gathering, fall for hunting and harvesting, and winter for storytelling and preparing for the next cycle.

The Expansive Algonquian Nations

The Algonquian-speaking peoples were the most widespread linguistic group in North America, and in the Northeast Woodlands, they occupied vast territories along the Atlantic coast and westward into the Great Lakes region. Unlike the more sedentary Iroquoian nations, many Algonquian groups were semi-nomadic, moving seasonally to optimize hunting, fishing, and gathering opportunities. Their dwellings were typically wigwams or wetus – dome-shaped structures made from saplings covered with bark, reed mats, or animal hides, designed to be easily constructed, dismantled, and transported.

Among the prominent Algonquian nations were:

- The Wampanoag: Living in what is now southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode Island, the Wampanoag are perhaps best known for their initial contact with the Pilgrims at Plymouth in 1620. Their leader, Massasoit Ousamequin, forged an alliance that allowed the struggling colonists to survive their first harsh years. Tisquantum (Squanto), a Patuxet Wampanoag man who had learned English after being captured and taken to Europe, famously aided the Pilgrims as an interpreter and guide, teaching them how to cultivate native crops like corn, beans, and squash, known as the "Three Sisters." This knowledge was crucial, as these crops formed the agricultural bedrock for many Northeastern tribes, providing a balanced diet and sustainable farming method. However, this early cooperation soon gave way to increasing land encroachment and conflict, culminating in King Philip’s War (1675-1678), a devastating conflict that decimated Indigenous populations and fundamentally altered the power dynamics in New England.

- The Lenape (Delaware): Revered by many Algonquian nations as "grandfathers," the Lenape originally occupied a vast territory spanning parts of modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. They were skilled farmers, hunters, and fishermen, and their society was organized into three main divisions: Munsee, Unami, and Unalachtigo. The Lenape were among the first to face the full brunt of European colonization, experiencing immense pressure from Dutch, Swedish, and English settlers, leading to significant land loss and forced displacement, pushing many westward.

- The Narragansett: Centered in present-day Rhode Island, the Narragansett were powerful traders and formidable warriors, maintaining significant influence over smaller neighboring tribes. They engaged in extensive trade networks, utilizing wampum (beads made from quahog and whelk shells) not only as a form of currency but also as a ceremonial object and a historical record, woven into intricate belts that chronicled treaties and significant events.

- The Abenaki: Occupying northern New England (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont) and parts of Quebec, the Abenaki were a confederation of smaller tribes, often allied with the French during colonial conflicts. Their lives were deeply intertwined with the region’s rivers, which provided both sustenance and transportation.

- The Mahican: Located along the Hudson River Valley in New York, the Mahican were an important intermediary in the fur trade between interior tribes and European traders. Like many, they suffered greatly from disease and colonial expansion.

- The Pequot and Mohegan: These related tribes inhabited southeastern Connecticut. The Pequot were a dominant force until the devastating Pequot War of 1637, a brutal conflict that saw the near annihilation of the tribe and set a grim precedent for colonial-Indigenous relations. The Mohegan, under their sagamore Uncas, allied with the English during this war, leading to their distinct historical path.

The Enduring Iroquoian Confederacy

West of the Algonquian territories, primarily in what is now upstate New York, resided the Iroquoian-speaking nations. Unlike their Algonquian neighbors, the Iroquoian peoples were primarily agriculturalists, establishing permanent, fortified villages surrounded by fields of corn, beans, and squash. Their iconic dwelling was the "longhouse" – an elongated, communal bark-covered structure, sometimes over 200 feet long, housing multiple related families within a matrilineal clan system.

The most famous and influential Iroquoian entity was the Haudenosaunee (pronounced "hoo-dee-noh-SHAW-nee"), meaning "People of the Longhouse," commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy or the League of Five Nations (later Six Nations). Formed sometime between the 12th and 15th centuries, this sophisticated political and military alliance was initially comprised of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations. The Tuscarora, an Iroquoian-speaking tribe from North Carolina, joined in the early 18th century, making it the Six Nations.

The Confederacy was founded on the principles of the Great Law of Peace (Kayanerekowa), a constitution that promoted unity, peace, and mutual defense among its member nations, ending generations of inter-tribal warfare. This complex system of governance, featuring a Grand Council of chiefs selected by clan mothers (who held significant political power in their matrilineal society), influenced democratic thought and is even cited by some historians as a potential inspiration for elements of the U.S. Constitution.

The Haudenosaunee’s strategic location and formidable organization made them a dominant power in the Northeast, playing a pivotal role in the colonial struggles between the French and British, often aligning with one side or the other to protect their lands and interests. Their long-standing presence and influence created a distinct cultural heartland within the Woodlands.

Shared Threads and Unique Tapestries

Despite their linguistic and some cultural differences, Northeast Woodlands tribes shared many commonalities. Oral tradition was paramount, with stories, myths, and legends passed down through generations, serving as historical records, moral lessons, and spiritual guidance. A deep reverence for the natural world and a holistic worldview, where humans were part of an interconnected web of life, permeated their spiritual practices and daily lives. Ceremonies often revolved around the agricultural cycle, hunting success, or rites of passage.

Art forms flourished, including intricate beadwork, porcupine quillwork, pottery, and the carving of wooden masks and effigies. Wampum belts, as mentioned, served not only as decorative items but as vital mnemonic devices for recounting history and treaties. Warfare, though present, was often ritualized, focused on demonstrating bravery, taking captives (who could be adopted), or maintaining balance, rather than outright conquest and annihilation, prior to the arrival of Europeans.

The Unfolding of History: European Contact and Its Aftermath

The arrival of Europeans brought monumental and often devastating changes. Initial interactions involved trade – furs for European goods like metal tools, firearms, and textiles. While these goods initially seemed beneficial, they quickly led to dependency and intensified inter-tribal rivalries over hunting territories.

Far more catastrophic was the introduction of Old World diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza. Indigenous peoples had no immunity, and epidemics swept through communities, often wiping out 90% or more of populations, crippling social structures and economies. "It was as if the very air became a weapon," noted one historian, describing the unseen devastation that preceded direct conflict.

As European settlements expanded, land became the primary source of conflict. Treaties were often misunderstood, violated, or coerced. Tribes found themselves caught in the geopolitical struggles between colonial powers, forced to choose sides in conflicts like the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, often with dire consequences regardless of their allegiance. Forced removals, cultural assimilation policies, and the relentless pressure of westward expansion continued long after the colonial period, pushing many tribes from their ancestral lands.

Resilience and Revival: The Living Legacy

Despite centuries of immense hardship, dispossession, and attempts at cultural erasure, the Indigenous peoples of the Northeast Woodlands have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Many nations, though vastly reduced in population and territory, survived. Today, they are actively engaged in cultural revitalization efforts, reclaiming their languages, traditional ceremonies, arts, and historical narratives. Sovereignty movements are strong, with tribes pursuing land claims, economic development (including casinos and other enterprises), and self-governance.

The Wampanoag, Narragansett, Lenape, Mohican, and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, among many others, are not relics of the past but vibrant, living communities. Their stories are not merely historical footnotes but essential chapters in the broader American narrative. They remind us that the forests and waterways of the Northeast are not just natural landscapes, but ancestral homelands imbued with thousands of years of human history, wisdom, and an enduring spirit of stewardship.

To truly understand the Northeast Woodlands is to acknowledge that these lands were, and continue to be, nurtured by the diverse and resilient Indigenous nations who have always been, and remain, its true guardians. Their voices, their history, and their continued presence are vital to the identity and future of the region.