The Shadow of the "Shining City": Manifest Destiny’s Catastrophic Impact on Native Americans

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

In the annals of American history, few concepts are as simultaneously revered and reviled as "Manifest Destiny." Coined in 1845 by journalist John O’Sullivan, it was the fervent belief that the United States was divinely ordained to expand its dominion across the North American continent, spreading democracy and capitalism from the Atlantic to the Pacific. To its proponents, it was a noble, God-given mission, promising prosperity and progress. To the indigenous peoples who already inhabited these vast lands, it was a death knell, ushering in an era of unprecedented violence, displacement, cultural destruction, and profound, enduring trauma.

Manifest Destiny was not merely a political doctrine; it was a potent cultural ideology that dehumanized Native Americans, portraying them as "savages," "obstacles," or "primitive" societies incapable of self-governance or land stewardship. This pervasive narrative justified the systematic dispossession of indigenous lands and the brutal subjugation of their peoples, transforming a continent teeming with diverse, thriving nations into a frontier ripe for "civilization" and exploitation. The "shining city on a hill" envisioned by American exceptionalists cast a long, dark shadow over millions of Native lives.

The Great Land Grab: Treaties as Tools of Dispossession

At the heart of Manifest Destiny’s impact was the insatiable hunger for land. For centuries, hundreds of distinct Native American nations, each with unique cultures, languages, and governance systems, had cultivated, hunted, and lived in harmony with the vast North American landscape. Their relationship with the land was spiritual and communal, a stark contrast to the European concept of individual ownership and exploitation.

As the United States expanded, its primary method of acquiring Native lands was through treaties. From the late 18th century onward, hundreds of treaties were signed between the U.S. government and various Native nations, ostensibly recognizing their sovereignty and land rights. However, these agreements were often negotiated under duress, with unequal bargaining power, and frequently violated by the U.S. government as soon as new resources were discovered or settlers demanded more territory.

One of the most significant early expansions driven by this land hunger was the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. While celebrated as a triumph of American diplomacy, it effectively doubled the size of the nascent United States, giving it claim to vast territories west of the Mississippi River that were, in reality, the ancestral homes of dozens of Native American tribes. This purchase, made without any consultation or consent from the indigenous inhabitants, set a precedent for future land appropriations, signaling that Native sovereignty was, at best, a temporary inconvenience.

The pattern was predictable: a treaty would be signed, land would be ceded, settlers would encroach, conflicts would arise, and a new, often more punitive, treaty would be forced upon the Native nation, leading to further land loss. This relentless cycle chipped away at Native territories until only fragments remained.

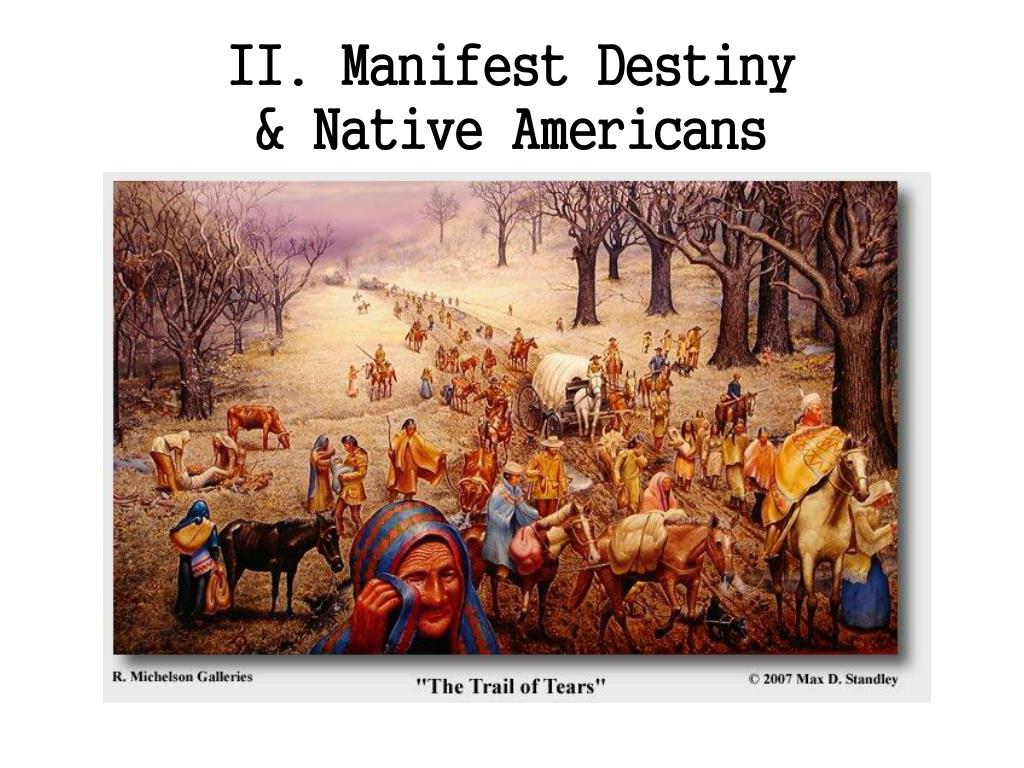

The Trail of Tears and Forced Removals

The most infamous and brutal manifestation of this land hunger was the policy of forced removal, culminating in the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Championed by President Andrew Jackson, a man who built his political career on fighting Native Americans, this act authorized the forced relocation of thousands of Native Americans from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma).

The so-called "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – had adopted many aspects of American culture, including writing systems, constitutional governments, and farming practices. Despite their efforts to assimilate and assert their sovereign rights through legal means, they were deemed an impediment to white expansion. The Cherokee Nation, in particular, fought their removal through the U.S. court system, achieving a landmark victory in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), where the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled that Georgia had no jurisdiction over Cherokee lands.

However, President Jackson famously defied the ruling, allegedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." With federal troops, including those led by General Winfield Scott, at their backs, approximately 16,000 Cherokees were rounded up in 1838 and forced to march over 1,000 miles in brutal winter conditions. This forced exodus became known as the "Trail of Tears" (Nunna daul Isunyi in Cherokee). Over 4,000 Cherokees, a quarter of their population, perished from disease, starvation, and exposure along the way.

John G. Burnett, a soldier who marched with the Cherokees, later recounted the horrors: "I saw helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and their houses set a fire… I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six-horse wagons and started toward the west." The Trail of Tears was not an isolated incident but the most devastating example of a broader policy that displaced tens of thousands of Native Americans across the continent, shattering their communities and severing their sacred ties to their homelands.

Warfare and Massacres: The Brutality of the Frontier

Manifest Destiny’s expansion was rarely peaceful. The clash of cultures and the relentless encroachment on Native lands inevitably led to generations of conflict, often referred to as the "Indian Wars." These were not merely battles but a prolonged, asymmetric struggle where the technological and numerical superiority of the U.S. military often overwhelmed Native resistance.

The U.S. military employed brutal tactics, including targeting non-combatants and destroying Native food sources and villages, aiming to break the will of the people. Tragedies like the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, where Colorado Volunteers brutally murdered over 150 Cheyenne and Arapaho women, children, and elderly, or the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were slaughtered by U.S. soldiers, stand as chilling monuments to the savagery of the frontier.

These massacres were often justified by the prevailing dehumanizing rhetoric that painted Native Americans as inherently violent or subhuman. General Philip Sheridan, a prominent figure in the post-Civil War Indian Wars, is infamously, though perhaps apocryphally, credited with the statement, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," a sentiment that undeniably reflected the prevailing attitudes of many military and civilian leaders. The wars decimated Native populations, broke tribal structures, and forced survivors onto ever-shrinking reservations.

Cultural Erasure and Assimilation: "Kill the Indian, Save the Man"

Beyond physical conquest, Manifest Destiny also fueled a concerted effort to eradicate Native American cultures. The belief that indigenous ways of life were inherently inferior and a barrier to "progress" led to policies aimed at forced assimilation. The philosophy was encapsulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, who famously declared, "Kill the Indian, save the man."

Native American children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to boarding schools far from their homes. Here, their hair was cut, their traditional clothing replaced, and they were forbidden from speaking their native languages or practicing their spiritual traditions. The goal was to strip them of their cultural identity and indoctrinate them into Euro-American norms, often through harsh discipline and abuse. This policy inflicted deep psychological wounds that continue to affect Native communities today, contributing to intergenerational trauma.

Simultaneously, the Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act) further eroded Native sovereignty and land ownership. It broke up communally held tribal lands into individual allotments, intended to force Native Americans into farming and private property ownership, mirroring American agrarian ideals. Surplus lands, often the most fertile, were then sold off to non-Native settlers. This act resulted in the loss of millions of acres of Native land, fragmented tribal cohesion, and further impoverished Native communities.

A Legacy of Trauma and Resilience

The shadow of Manifest Destiny stretches into the present day. Its legacy is visible in the disproportionate poverty, health disparities, and social challenges faced by many Native American communities. The trauma of forced removal, cultural suppression, and violence has been passed down through generations, manifesting in higher rates of substance abuse, mental health issues, and a continuing struggle for identity and self-determination.

Yet, despite the immense suffering and systematic oppression, Native American nations have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Against all odds, many have preserved their languages, revitalized their cultures, and continue to fight for their treaty rights, sovereignty, and the recognition of their rightful place in American society. Movements for landback, environmental justice, and cultural revitalization are powerful testaments to the enduring spirit of indigenous peoples.

Manifest Destiny, once heralded as a glorious chapter in American expansion, must now be critically examined for its devastating consequences. It was not merely about westward expansion; it was about the violent subjugation of diverse peoples, the systematic destruction of their societies, and the profound theft of their heritage. Understanding its true impact on Native Americans is not just an act of historical reckoning, but a vital step towards acknowledging the past, fostering healing, and building a more just and equitable future for all who share this land.